This is Part 1 of a multi-part article on the history of the Office of Construction and Facilities Management. This series is the first set of articles within a larger project covering the histories of VA Central Office’s directorates.

—

The story of the Office of Construction and Facilities Management (CFM) is one of civil servants working to create and maintain the physical spaces where VA fulfills its duty to care for those who have served in our nation’s military and for their families, caregivers, and survivors.

The approaches CFM and its predecessors took to completing this monumental task have evolved over time, changing with the size and needs of the country’s Veteran population. During some periods, authority over construction projects was centralized within the VA Central Office, while at other times the structure was reorganized to delegate oversight duties to the regional or local level. The role of the office also changed with time, taking on new responsibilities, losing others, and then sometimes regaining functions in periods of consolidation. For more than a century, the construction offices of the Veterans Bureau, Veterans Administration, and the Department of Veterans Affairs have helped to shape VA’s vast network of medical centers, national cemeteries, and administrative offices, which CFM continues to maintain today.

—

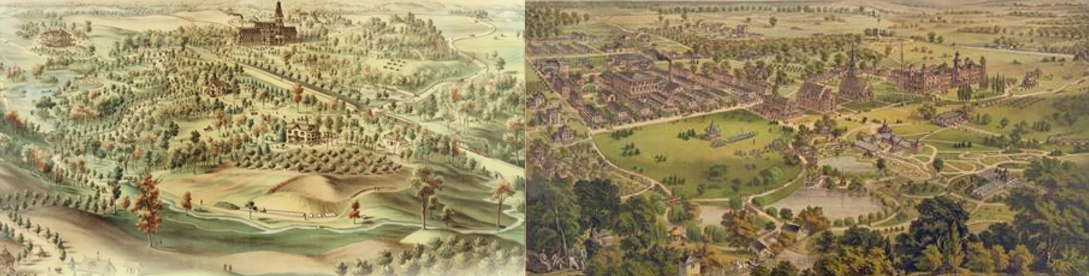

Even before the Veterans Bureau created a formal office dedicated to the construction and maintenance of facilities for Veterans in the United States, the Federal government began erecting buildings to house and care for the nation’s Veteran population. In the final months of the Civil War, Congress passed legislation establishing the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (NHDVS). Congress also created a Board of Managers to oversee the NHDVS system, and one of their duties was to manage the construction of each of the National Home’s branches.[1] Though many of the branches reflected similar architectural styles, there was little standardization in the construction of the buildings at NHDVS locations. Individual members of the Board of Managers often had influence over the construction at specific branches, and the Board regularly selected different architectural firms to design the campuses.[2] This decentralized and individualistic approach to construction within the NHDVS system continued into the early twentieth century.

The large increase in the country’s Veteran population after World War I required the Federal government to expand the number of facilities where Veterans could receive care. During the war, Federally-funded Veterans’ care shifted from the domiciliary care model used in the NHDVS system to short-term hospital care, where Veterans were treated, placed in physical and vocational rehabilitation programs, and eventually returned to civilian life. Several entities within the United States Treasury Department were tapped to increase the number of hospital beds across the country through purchasing, leasing, and constructing facilities.[3] Groups involved in this effort included the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the Public Health Service, the Consultants on Hospitalization committee, and the Office of the Supervising Architect, the latter of which was responsible for overseeing much of the construction completed by the Federal government between the Civil War and the 1920s.[4] Congress passed legislation to guide and fund this expansion starting in 1919. Two additional bills, introduced by Representative John W. Langley and known as the first and second Langley bills, were passed in 1921 and 1922. Together, these three bills appropriated more than $44 million for hospital acquisition, alteration, and construction.[5]

By the early 1920s, it was apparent that many aspects of Veteran care, including both the organization and state of the medical infrastructure, were not effectively meeting the post-war need. To streamline and improve many of the benefits owed to Veterans, Congress and the administration of President Warren G. Harding worked to create the Veterans Bureau in August 1921, combining the responsibilities of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the Federal Board of Vocational Education, and the Public Health Service (PHS).[6] Oversight of the construction and operation of Veteran hospitals remained the responsibility of entities within the Treasury Department until April 1922, when Congress passed the second Langley bill, giving the bureau’s director control over construction, and President Harding transferred all existing and planned Veteran medical facilities to the Veterans Bureau through Executive Order 3669.[7]

With that transfer, the PHS’s Maintenance Unit, which managed the construction and repair of Veteran hospitals within the PHS Hospital Division, became the Veteran Bureau’s Maintenance and Repair Section within its Staff Assistant’s Office, under the Office of the Director.[8] Overseen by architect Charles H. Stratton, the Maintenance and Repair Section was responsible for the repair of the bureau’s existing facilities, but it did not manage new construction. Stratton previously worked for the PHS and would later serve as the Chief of the Design Subdivision within the bureau’s Construction Division.[9] In October 1922, the Maintenance and Repair Section was relocated to the bureau’s Supply Division.[10] Between 1922 and 1923, the Veterans Bureau outsourced construction of new buildings to the Quartermaster General of the War Department and the Navy Department’s Bureau of Yards and Docks.[11]

The Veterans Bureau’s reliance on outside agencies in the construction of their facilities soon came to an end. By early 1923, the bureau had a new leader – Frank T. Hines – who set his sights on creating a more efficient and internally controlled construction program.

—

Check back soon for Part 2, Building the Veterans Administration: Establishing the Office, Setting the Standard, and Constructing VA’s Hospital Network.

[1] Suzanne Julin, National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers Assessment of Significance and National Historic Landmark Recommendations (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2007), 12-13.

[2] Ibid., 15-16; Trent Spurlock, Karen E. Hudson, and Dean Doerrfeld, “United States Second Generation Veterans Hospitals,” National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 201, E-35.

[3] Julin, National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers Assessment of Significance and National Historic Landmark Recommendations, 35-36.

[4] Spurlock, et al., “United States Second Generation Veterans Hospitals,” E-7, E-47 – E-51; An Act to Authorize an Appropriation for Construction at the Mountain Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Johnson City, Tennessee, H.R. 6340, 71st Cong. § 2 (1930); Judith H. Robinson and Stephanie S. Foell, Growth, Efficiency, and Modernism: GSA Buildings of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s (Washington, D.C.: General Services Administration, 2003), 21-22; Robert D. Leigh, Federal Health Administration in the United States (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1927), 168-173.

[5] An Act to Authorize the Secretary of the Treasury to Provide Hospital and Sanatorium Facilities for Discharged Sick and Disabled Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, H.R. 13026, 65th Cong. § 3 (1919); An Act Providing Additional Hospital Facilities for Patients of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance and of the Federal Board for Vocational Education, Division of Rehabilitation, and For Other Purposes, H.R. 15894, 66th Cong. § 3 (1921); An Act to Authorize an Appropriation to Enable the Director of the United States Veterans’ Bureau to Provide for the Construction of Additional Hospital Facilities and to Provide Medical, Surgical, and Hospital Services and Supplies for Persons who Served in the World War, the Spanish-American War, the Philippine Insurrection, and the Boxer Rebellion, and are Patients of the United States Veterans’ Bureau, H.R. 10864, 67th Cong. § 2 (1922).

[6] Spurlock, et al., “United States Second Generation Veterans Hospitals,” E-8; Jeffrey Seiken, “1921: Veterans Bureau is born – precursor to Department of Veteran Affairs,” VA History Office, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, November 12, 2021.

[7] Marguerite T. Hays, A Historical Look at the Establishment of the Department of Veterans Affairs Research and Development Program (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development), 9; Warren G. Harding, Exec. Order 3669, April 29, 1922. National Archives and Records Administration, General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11.

[8] U.S. Treasury Department, Public Health Service, Annual Report of the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service of the United States for the Fiscal Year 1922 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1922), 248-249.

[9] U.S. Veterans’ Bureau, Annual Report of the Director, United States Veterans’ Bureau, for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1923 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1923), 777; U.S. Veterans’ Bureau, Annual Report of the Director, United States Veterans’ Bureau, for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1922 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office 1922), 1; “Try to ‘Pass Buck’ in Morse Deal Probe,” St. Joseph News-Press (St. Joseph, Missouri), November 2, 1923.

[10]U.S. Veterans’ Bureau, Annual Report of the Director, United States Veterans’ Bureau, for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1922, 1; U.S. Veterans’ Bureau, Annual Report of the Director, United States Veterans’ Bureau, for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1923, 778.

[11] U.S. Veterans’ Bureau, Annual Report of the Director, United States Veterans’ Bureau, for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1924 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1924), 494.

By Wes Nimmo

former VA History Office Historian