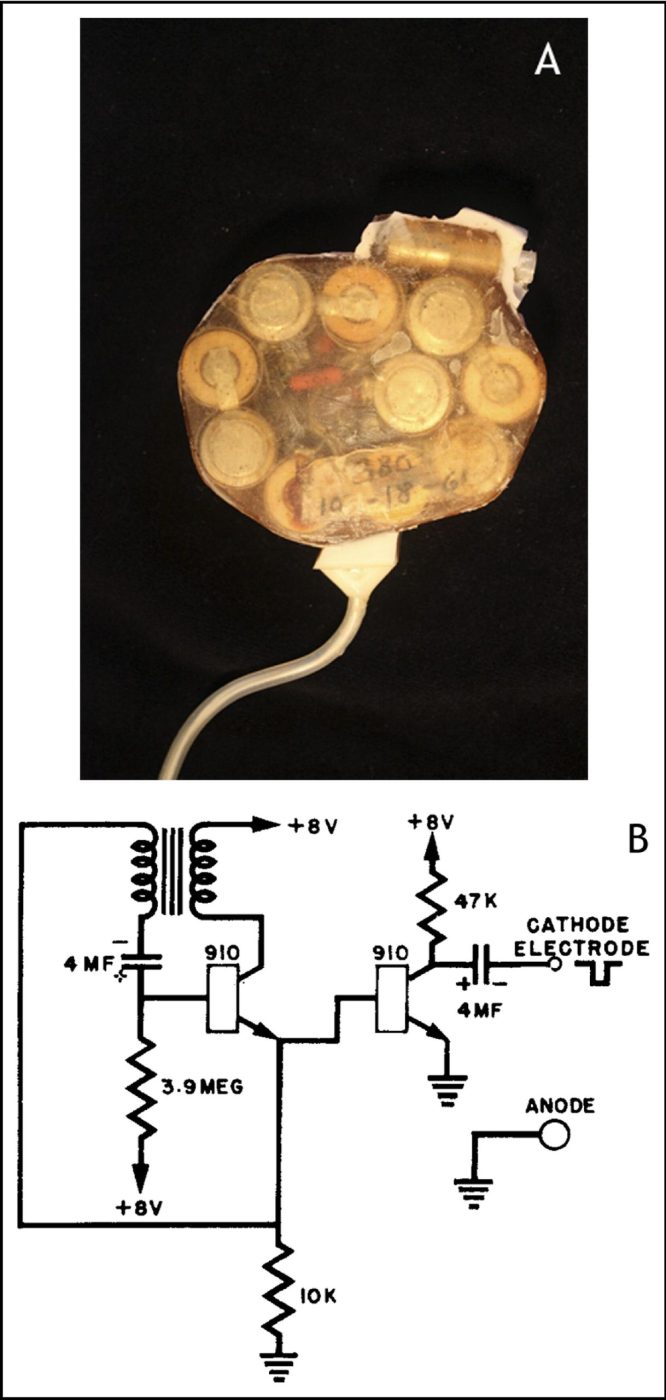

In 1960, a VA research team led by surgeon William Chardack inserted what he described as a “battery-operated gadget about twice as big as a spool of Scotch tape and much the same shape” under the skin of a patient suffering from a complete heart block. The compact “gadget”- better known as the cardiac pacemaker – sent electrical signals to stimulate the heart and help it maintain a regular rhythm. A bundle of ten mercury zinc cells generated the pulses. While other researchers had created external pacemakers, Dr. Chardack’s device was revolutionary because it was implantable and powered by its own battery pack. The internal cardiac pacemaker developed by his team transformed the field of cardiac medicine.

Work on the pacemaker began in 1958 at the VA hospital in Buffalo, New York. Dr. Chardack’s team included another surgeon, Andrew Gage, and electrical engineer Wilson Greatbatch. Together, they focused on the many possibilities of electricity in medicine. The group was known as the bow tie team on account of their penchant for wearing bow ties to work each day. It was the engineer Greatbatch who actually designed the pacemaker and he built the first 50 by hand in his backyard workshop. They tested a prototype of the device on a dog so they could observe the benefits of cardiac electrotherapy. Two years later, they were ready to implant the cardiac pacemaker in a human. The operation was a success and the man lived for another two years before dying of unrelated causes. Subsequent patients who received the pacemaker lived for as long as 20 years after the surgery.

The bow tie team continued to refine their invention in the 1960s and early 1970s. In 1972, with Dr. Chardack assisting, Dr. Gage implanted the first nuclear-powered cardiac pacemakers in patients at the Buffalo VA hospital. The same year, Greatbatch pioneered the use of long-lasting lithium-iodine cells as a power source for pacemakers.

Although surgical techniques and pacemaker technologies have evolved over the years, the basic design remains similar to the device introduced to the medical world by Dr. Chardack and his collaborators in 1960. The cardiac pacemaker developed by VA researchers has improved the length and quality of life for thousands of Veterans and millions of people worldwide.

VA HISTORY IN FOCUS: In 1960, a VA research team led by surgeon William Chardack inserted what he described as a “battery-operated gadget about twice as big as a spool of Scotch tape and much the same shape” under the skin of a patient suffering from a complete heart block. The gadget was the first cardiac pacemaker.

VA HISTORY IN FOCUS: In 1960, a VA research team led by surgeon William Chardack inserted what he described as a “battery-operated gadget about twice as big as a spool of Scotch tape and much the same shape” under the skin of a patient suffering from a complete heart block. The gadget was the first cardiac pacemaker. By Parker Beverly

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, Veterans Health Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

American prisoners of war from World War II, Korea, and Vietnam faced starvation, torture, forced labor, and other abuses at the hands of their captors. For those that returned home, their experiences in captivity often had long-lasting impacts on their physical and mental health. Over the decades, the U.S. government sought to address their specific needs through legislation conferring special benefits on former prisoners of war.

In 1978, five years after the United States withdrew the last of its combat troops from South Vietnam, Congress mandated VA carry out a thorough study of the disability and medical needs of former prisoners of war. In consultation with the Secretary of Defense, VA completed the study in 14 months and published its findings in early 1980. Like previous investigations in the 1950s, the study confirmed that former prisoners of war had higher rates of service-connected disabilities.

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.