On the south side of Florida’s St. Augustine National Cemetery, three squat pyramids and a single taller obelisk rise from the ground above the other nearby markers and headstones. The Dade Pyramids and Monument, as they are known, mark the resting place of the U.S. soldiers who died in the opening engagement of the Second Seminole War (1835-42). The memorial honors lives lost while also serving as a grim reminder of the brutal conflict that erupted when the Federal government tried to evict the Seminole people from their tribal lands in Florida.

In 1832, the United States negotiated the Treaty of Payne’s Landing signed by only some Seminole chiefs that gave the Seminoles three years to relocate to territory set aside for Native use west of the Mississippi River. Seminole leaders afterwards repudiated the agreement. In 1835, as the treaty deadline approached, both sides braced for battle. A Native leader named Osceola assembled approximately 1,000 warriors to resist any effort by U.S. troops to remove the Seminole.

In late December 1835, Maj. Francis Dade received orders to reinforce Fort King (near present-day Ocala), with the 107 regulars under his command. As the column neared the fort on December 28, Dade, who had been anticipating an ambush for days, grew lax and recalled his scouts. His decision proved fatal.

In a pine barren near present-day Bushnell, Florida, Seminole warriors led by another chief, Micanopy, attacked Dade’s troops from several sides. Dade and many of his fellow officers died in the first volley. Deprived of leadership, the remaining soldiers were unable to mount an effective defense. Only two or three men survived the ambush. It took the U.S. Army over two months to recover the bodies of the deceased and bury them on the battlefield.

The U.S. efforts to subjugate the Seminole turned into a long and costly campaign. The fighting finally petered out in 1842, without a formal agreement to end hostilities. The war inflicted grievous harm on the Seminole people. An uncounted number died and about 3,000 were forced to relocate west. However, several hundred refused to accept defeat and retreated into the Everglades region, where they continued to defy efforts to remove them.

The U.S. dead numbered over 1,400. In June 1842, the Army proposed transporting the remains of every U.S. soldier who perished during the war to St. Augustine for permanent interment in the burial plot at the Army’s St. Francis Barracks. Colonel William J. Worth also asked all officers and enlisted personnel in Florida to contribute a day’s pay from their salary to erect a monument to Dade and his men.

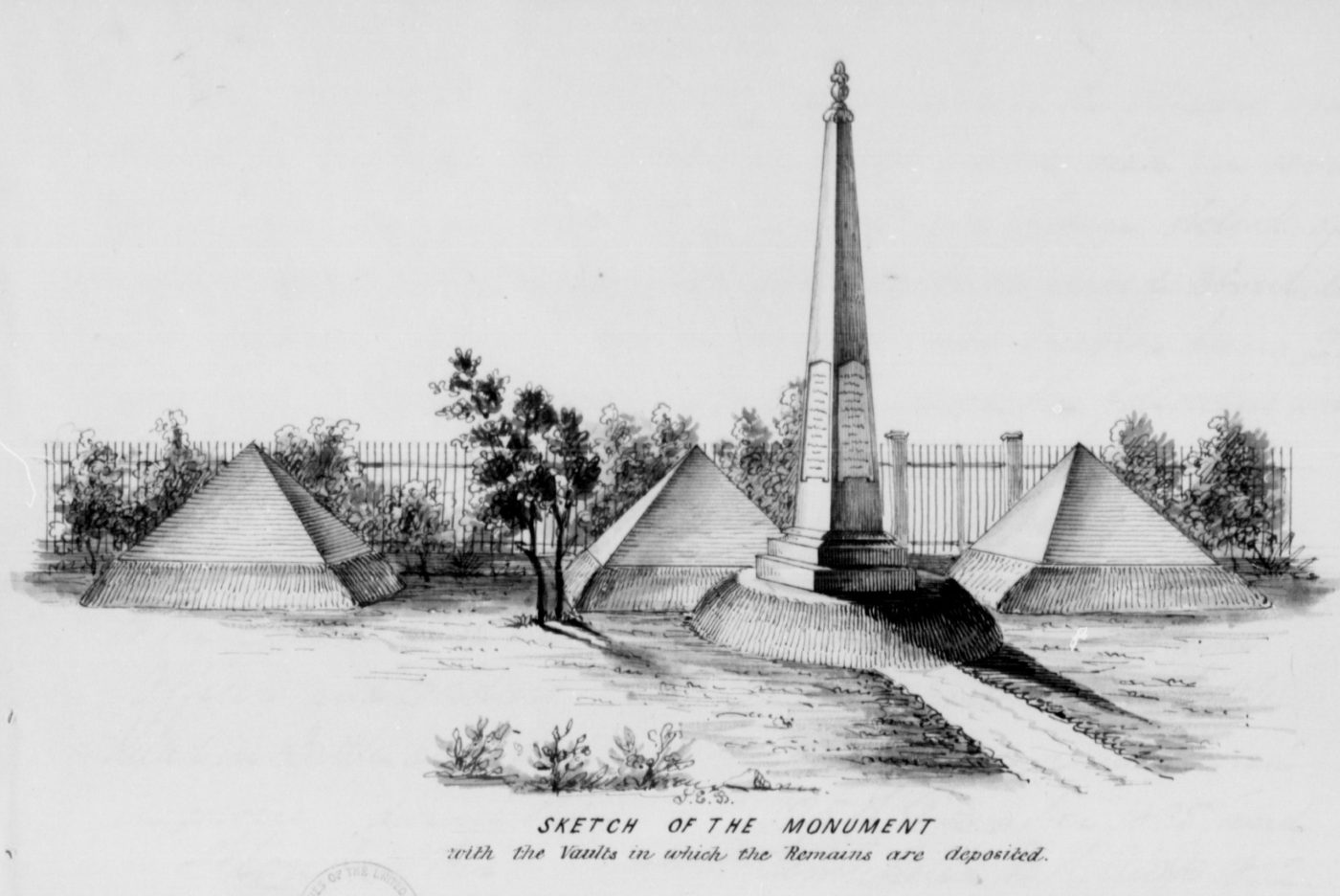

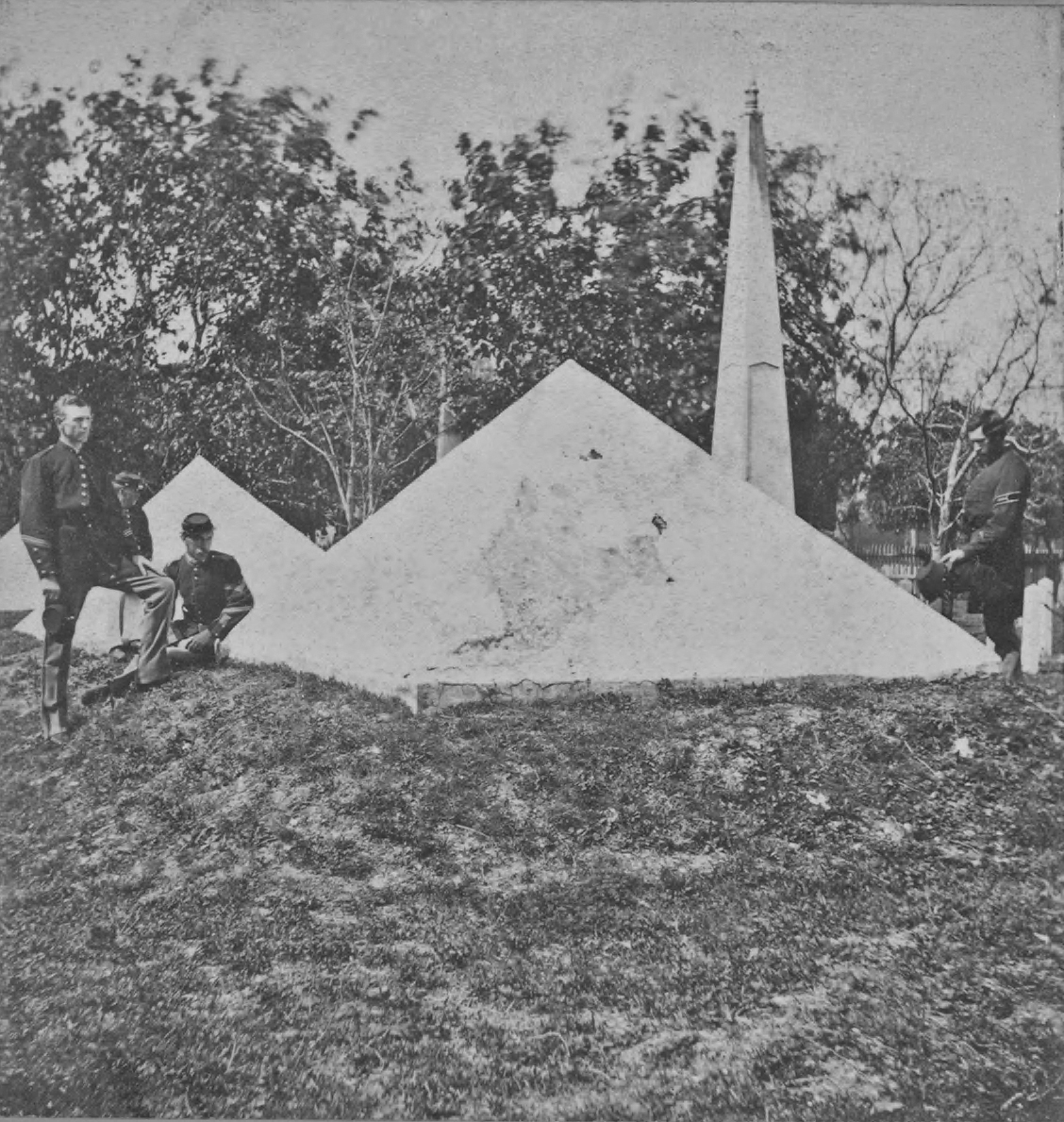

He intended to use the donations to construct three “suitable vaults” covered by “unostentatious monuments” for the deceased. The vaults were finished and the remains buried in a large ceremony held on August 15. Three five-foot tall pyramids stood above the vaults. The pyramids were made of coquina, a porous limestone rock composed of seashell fragments native to the area. A smooth layer of stucco painted white coated their exterior.

The estimated 165 persons interred in the vaults included not just the members of Dade’s company but other casualties from the war as well. Worth reported that the vaults and pyramids cost just $41.81, leaving him with $400 in unspent donations. He decided to use the leftover money to add an 18-foot marble obelisk atop a granite base to the burial site. The north face reads, “Sacred to the memory of the Officers and Soldiers killed in battle and died in service during the Florida War.”

The memorial attracted its share of visitors, but interest in the pyramids and obelisk waned over time. In the early 20th century, other sites related to the Dade ambush and the Seminole War came to overshadow this one. In 1921, the Florida state legislature appropriated funds to create a memorial park at the spot where the battle occurred. Initially known as the Dade Massacre Park, the state park has become a popular destination for locals and day-trippers interested in exploring its history or enjoying its many outdoor attractions.

In 1973, VA assumed responsibility for most of the Army’s national cemeteries, including St. Augustine. By then, Florida’s subtropical climate had worn away the stucco exterior of the three Dade Pyramids. VA chose to maintain the pyramids in the condition they were received, meaning without the whitewashed stucco. While the Dade Battlefield Historic State Park draws a crowd to its annual reenactment of the battle, VA performs the somber task of ensuring that the first and oldest memorialization of the U.S. soldiers who died in the Second Seminole War is properly preserved.

By Matthew Harris

Intern, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.