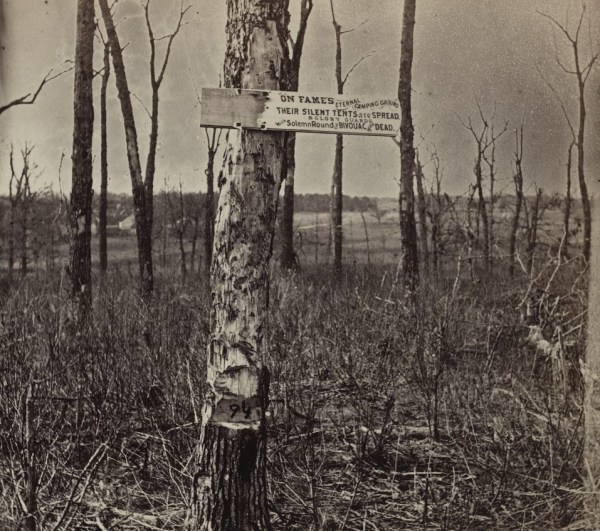

The mounted plaque stands in front of the headstones at Mobile National Cemetery in Alabama. The dark, cast-aluminum tablet draws a stark contrast to the sea of pearly marble beyond. Across its face in white lettering runs the sorrowful first stanza of Theodore O’Hara’s elegiac poem, “Bivouac of the Dead,” beginning with the verse “The muffled drum’s sad roll has beat / The Soldier’s last tattoo; / No more on life’s parade shall meet / That brave and fallen few.” Tablets bearing passages from O’Hara’s poem can be found in dozens of VA national cemeteries across the country. Originally written to honor the Kentucky volunteers who died in the Mexican War (1846-48), the poem now serves as a literary memorial to all lives lost in service to the nation.

Born in Danville, Kentucky, in 1820, Theodore O’Hara studied law as a young man and secured a position in the U.S. Treasury in 1845. However, the allure of soldiering was too strong for him. When the United States declared war on Mexico in 1846, he left his desk job and obtained a commission as a captain in the U.S. Army. He was promoted to brevet major for his gallant conduct in the campaign that led to the fall of the Mexican capital in 1847. A few years later, O’Hara took command of a contingent of Kentucky men who were veterans of the Mexican conflict and joined the extra-legal 1850-51 filibustering expedition to Cuba that sought to overthrow Spanish colonial rule on the island. The venture failed and he was wounded in a skirmish. Returning to Kentucky, he settled into work as a journalist. He took up arms once again at the start of the Civil War, joining the Confederate Army at the rank of colonel. O’Hara saw action in several major battles and survived the war, but he succumbed to typhoid fever in 1867 at the age of 47. Buried in Columbus, Georgia, he was subsequently reinterred in the state cemetery in Frankfort, Kentucky, in 1874 at the behest of the Kentucky legislature.

O’Hara was a man of letters and in the 1850s he enjoyed considerable success as a writer and editor at several major newspapers. But he also dabbled in poetry and his literary reputation rests largely on “Bivouac of the Dead” and another poem he authored, a tribute to “The Old Pioneer, Daniel Boone.” He wrote “Bivouac” of the Dead” to eulogize the many Kentucky soldiers who perished while fighting off a much larger Mexican force at the Battle of Buena Vista in February 1847. In 1850, the Kentucky legislature built a memorial to the fallen men at the cemetery in Frankfort, where many of them were buried after their remains were returned from Mexico. O’Hara’s poem was published the same year in the newspaper he was editing, The Franklin Yeoman. The final stanza references the newly raised monument and the men interred beneath: “Yon marble minstrel’s voiceless stone / In deathless song shall tell, / When many a vanquished ago has flown, / The story how ye fell; / Nor wreck, nor change, nor winter’s blight, / Nor Time’s remorseless doom, / Shall dim one ray of glory’s light / That gilds your deathless tomb.”

“Bivouac of the Dead” was reprinted several times in other newspapers prior to the Civil War. However, its popularity did not really take off until after the war when it was widely anthologized in literary publications such as Littell’s Living Age (1866) and Library of Poetry and Song (1871). In an 1874 booklet that included both O’Hara poems, Kentucky historian George Ranck lauded him as the nation’s “one elegiac poet of acknowledged genius.” Another Kentucky native and author, Susan B. Dixon, writing in the New York Times at the turn of the century, extolled “Bivouac of the Dead” in equally rapturous language: “It stands out alone, perfect in its beauty, its grandeur, its harmony, its sublime pathos, its exquisite and mournful tenderness, its glory of immortal light. It is in words what the great “Siegfried” funeral march is in music.”

Besides appearing frequently in print, “Bivouac of the Dead” also started turning up in cemeteries for the war dead after 1865. Lines from the poem were displayed on painted signboards at the gates and along the paths winding through the grounds. The massive archway called the McClellan gate that served as the original entrance to Arlington National Cemetery featured verses on both sides of the memorial. In the 1880s, the Army manufactured a set of seven cast-iron tablets inscribed with passages from the poem to replace the makeshift markers at the national cemeteries in its care. O’Hara’s name, however, was conspicuously absent from the plaques, most likely due to his service in the Confederate Army.

In the decades that followed, tablets disappeared or were removed from many cemeteries due to maintenance costs and possibly concerns about O’Hara’s connection to the Confederacy. By the 1990s, only 16 national cemeteries still had one or more tablets on display. The poem itself retained its appeal and it was frequently included in anthologies and poetry collections. In 2001, VA’s Under Secretary for Memorial Affairs, Robin L. Higgins, decided to revive the tradition of installing the poetic tablets at national cemeteries. The following year, VA awarded a contract to mass produce more than 100 cast-aluminum plaques inscribed with the first eight lines of the poem. Unlike the earlier tablets, these also included the title of the poem and, most importantly, Theodore O’Hara’s name. The plaques have been put in place at national cemeteries throughout the VA system, sharing O’Hara’s meditation on bravery and sacrifice with a new generation of visitors.

The poem in its entirety is available at this link.

By Emme Richards

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, VA History Office, Department of Veterans Affairs

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.

History of VA in 100 Objects

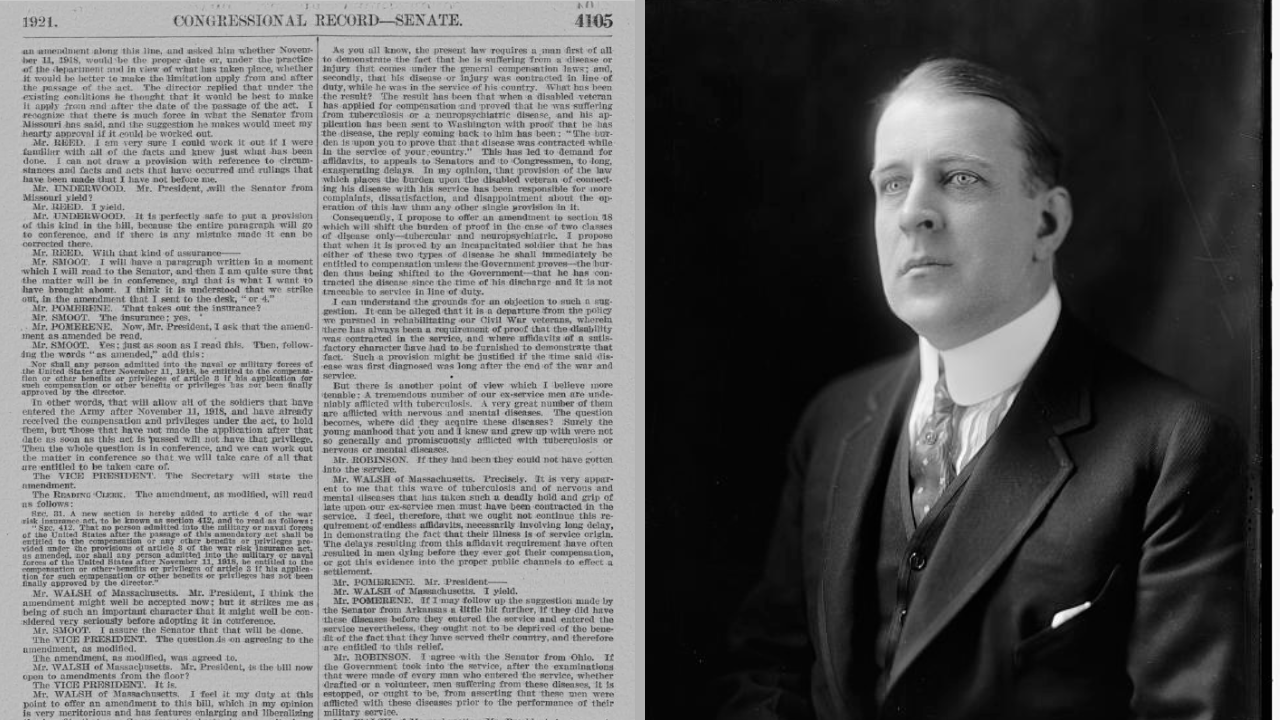

After World War I, claims for disability from discharged soldiers poured into the offices of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the federal agency responsible for evaluating them. By mid-1921, the bureau had awarded some amount of compensation to 337,000 Veterans. But another 258,000 had been denied benefits. Some of the men turned away were suffering from tuberculosis or neuropsychiatric disorders. These Veterans were often rebuffed not because bureau officials doubted the validity or seriousness of their ailments, but for a different reason: they could not prove their conditions were service connected.

Due to the delayed nature of the diseases, which could appear after service was completed, Massachusetts Senator David Walsh and VSOs pursued legislation to assist Veterans with their claims. Eventually this led to the first presumptive conditions for Veteran benefits.