Curator Corner

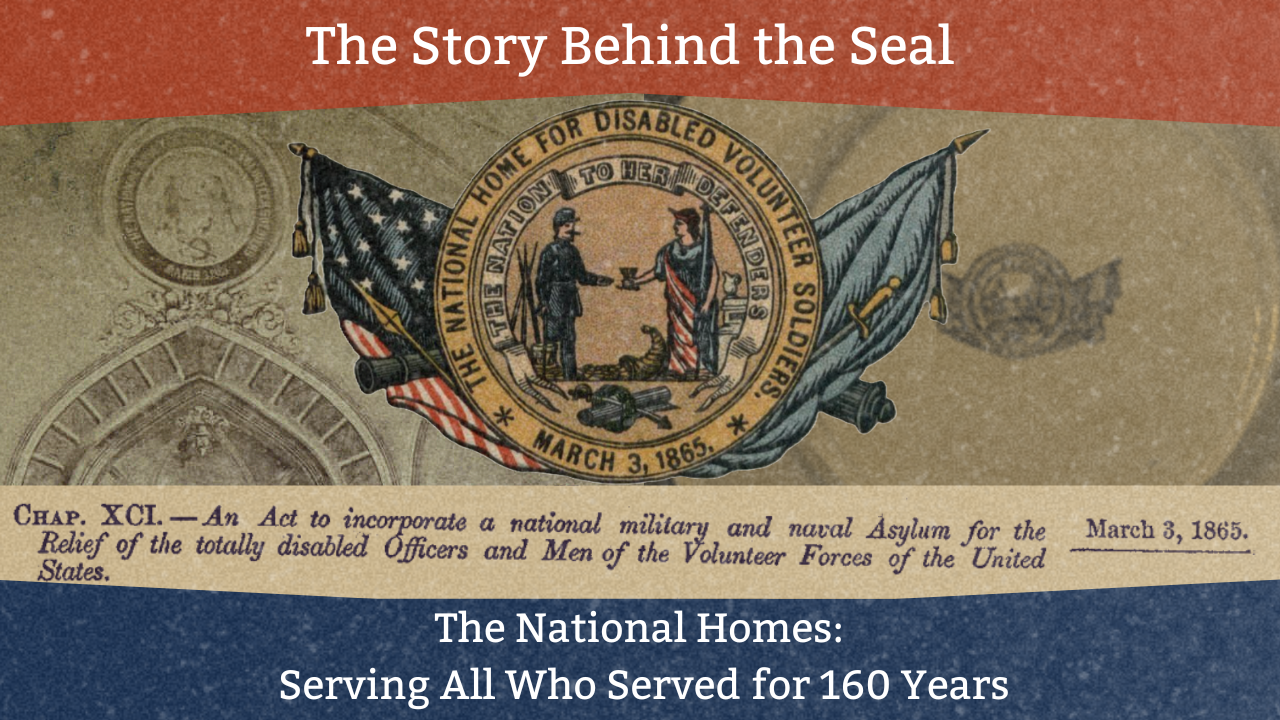

The Story Behind the National Homes’ Seal

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers turns 160 years old in 2025. The campuses are the oldest in the VA system, providing healthcare to Veterans to this day.

At the time of their establishment, they were the first of their type on this scale in the world. Within the NHDVS seal is the story that goes back 160 years ago.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 88: Civil War Nurses

During the Civil War, thousands of women served as nurses for the Union Army. Most had no prior medical training, but they volunteered out of a desire to support family members and other loved ones fighting in the war. Female nurses cared for soldiers in city infirmaries, on hospital ships, and even on the battlefield, enduring hardships and sometimes putting their own lives in danger to minister to the injured.

Despite the invaluable service they rendered, Union nurses received no federal benefits after the war. Women-led organizations such as the Woman’s Relief Corps spearheaded efforts to compensate former nurses for their service. In 1892, Congress finally acceded to their demands.

History of VA in 100 Objects

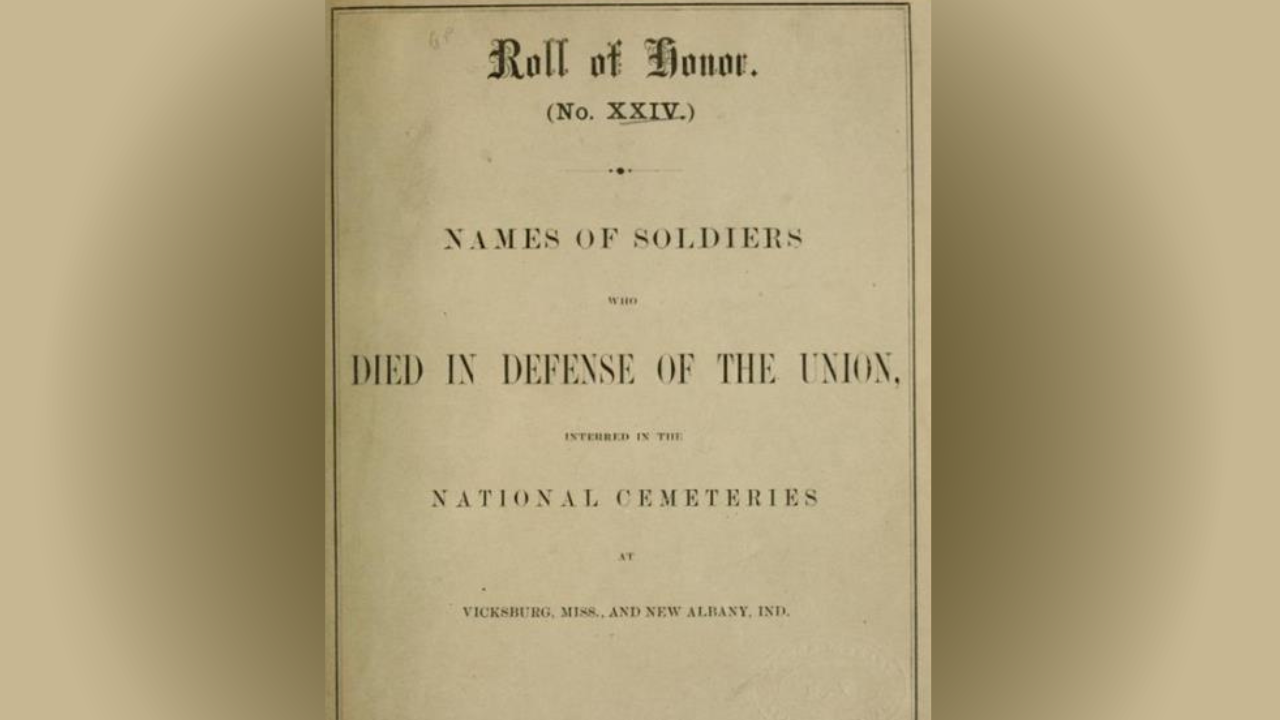

Object 86: The Roll of Honor

“The following pages are devoted to the memory of those heroes who have given up their lives upon the altar of their country, in defense of the American Union.”

So opened the preface to the first volume of the Roll of Honor, a compendium of over 300,000 Federal soldiers who died during the Civil War and were interred in national and other cemeteries. The genesis of this 27-volume collection published between 1865 and 1871 can be traced to Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs and the department he oversaw for a remarkable 21 years from 1861 to 1882.

History of VA in 100 Objects

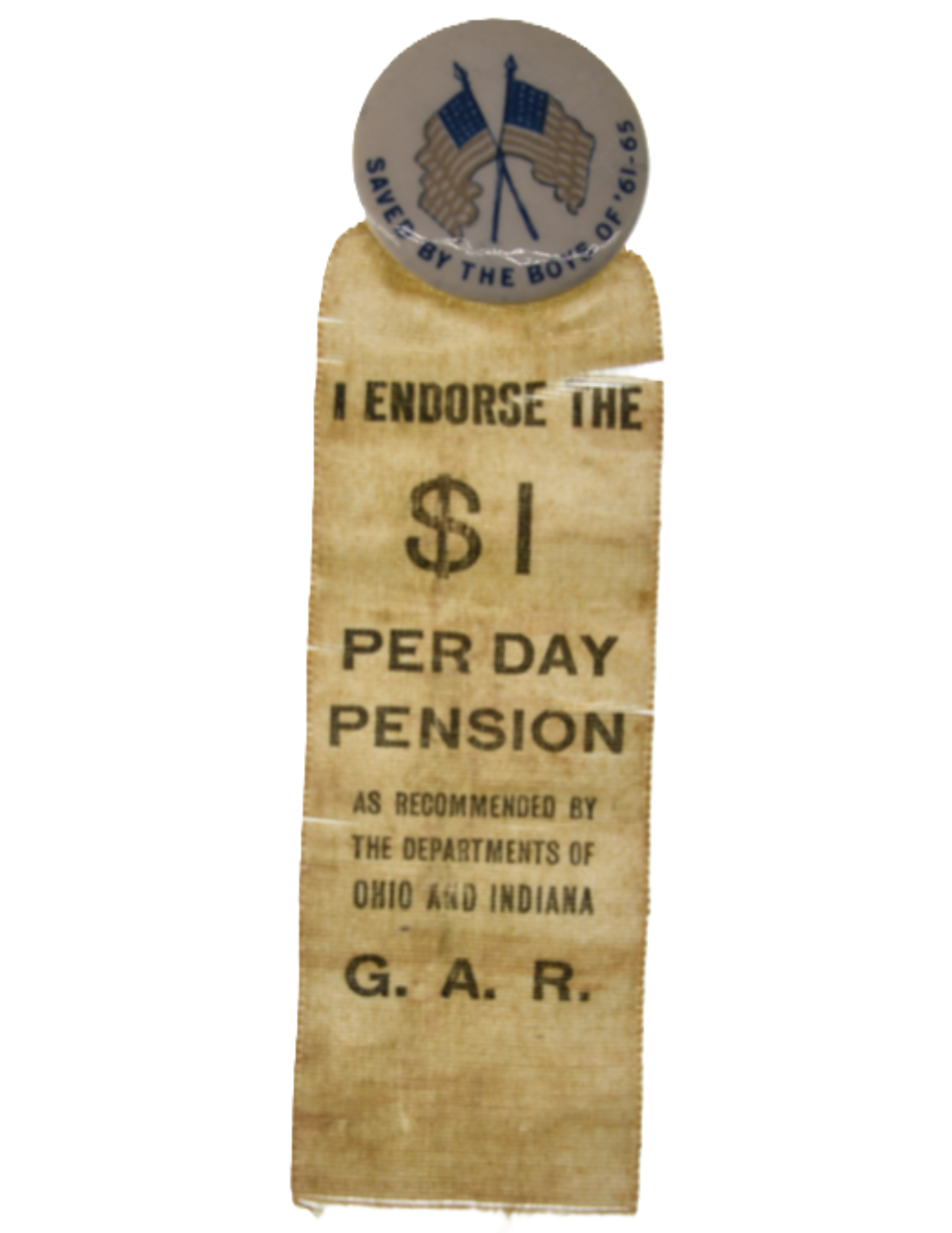

Object 85: Congressman Claypool’s “$1 Per Day Pension” Ribbon

Founded in 1866 as fraternal organization for Union Veterans, the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) embraced a new mission in the 1880s: political activism. The GAR formed a pension committee in 1881 for the express purpose of lobbying Congress for more generous pension benefits.

An artifact from the political wrangling over pensions is now part of the permanent collection of the National VA History Center in Dayton, Ohio. The item is a small pension ribbon displaying the message: “I endorse the $1 per day pension as recommended by the Departments of Ohio and Indiana G.A.R.” The button attached to the ribbon features two American flags and the phrase “saved by the boys of ’61-65.” The back of the ribbon bears the signature of Horatio C. Claypool, a Democratic judge who ran for the seat in Ohio’s eleventh Congressional district in the 1910 mid-term elections.

Featured Stories

The Historic Streets of the VA Medical Center in Prescott, Arizona

Ever wonder where some historic street names come from? That's the question that pops up at the VA Medical Center in Prescott, Arizona. Multiples names are displayed on white signs, such as Holmberg, Allee and Whipple. Who are they? Dive in and find out.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 84: Gettysburg Address Tablet

President Abraham Lincoln is one of the most revered figures in American history. Rankings of U.S. presidents routinely place him at or near the top of the list. Lincoln is also held in high esteem at VA. His stirring call during his second inaugural address in 1865 to “care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan” embodies the nation’s promise to all who wear the uniform, a promise VA and its predecessor administrations have kept ever since the Civil War.

Ever since Lincoln first uttered those memorable words in November 1863, the Gettysburg Address has been linked to our national cemeteries. In 1908, Congress approved a plan to produce a standard Gettysburg Address tablet to be installed in all national cemeteries in time for the centennial of President Lincoln’s birth on February 12, 1909.

Curator Corner

What’s in the Box? Fire Safety and Prevention at the National Homes

Fire safety may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about Veteran care, but during the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers period (1865-1930), it was a critical concern. With campuses largely constructed of wooden-frame buildings, housing thousands of often elderly and disabled Veterans, the risk of fire was ever-present. Leaders of the National Homes were keenly aware of this danger, as reflected in their efforts to establish early fire safety protocols.

Throughout the late 19th century, the National Homes developed fire departments that were often staffed by Veteran residents, and the Central Branch in Dayton even had a steam fire engine. Maps from this era, produced by the Sanborn Map Company for fire insurance purposes, reveal detailed records of fire prevention equipment and strategies used at the Homes. These records provide us with a rare glimpse into evolving fire safety measures in the late 19th and early 20th Century, all part of a collective effort to ensure the well-being of the many Veterans living there.

Curator Corner

Lincoln’s Promise, Lincoln’s Legacy: Historic Artifacts Recovered from Site of Dayton Statue

It all started when Bill DeFries, President of the American Veteran’s Heritage Center (AVHC), lost his wedding ring at the construction site for the statue of Abraham Lincoln on the campus of the Dayton VA Medical Center. He requested the assistance of the Dayton Diggers, a local nonprofit whose mission is to “research, recover, and document history” through their use of metal detector survey. The machines used by Dayton Diggers emit an electromagnetic field that responds to metal objects hidden below the ground surface. When they pinpoint a target, they use minimally invasive excavation to remove the object from the soil. In addition to the misplaced wedding band, their team uncovered historic artifacts that can be used to understand the history of Veteran care here in Dayton.

Curator Corner

What’s in the Box? 2nd Lt. George Fair’s 140 Year Journey

It started with a medal. Later on a button. Then, walks along the trails at the Dayton VA Medical Center and to the National Cemetery. Finally, it ended at a tall monument at the intersection of Monument Avenue and Main Street in downtown Dayton.

Well, it didn't quite end there. This was just the beginning in learning about the soldier, whose likeness sits atop the Montgomery County Soldier's Monument and stands watch at the main entrance to the Dayton VA Medical Center.

This is the story of a curator diving into the story of George Fair, Dayton's Veteran model and a 140 year journey.

Featured Stories

1870 Annual Report for the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers

Have you ever wondered where do historians, curators and archivists find all the information that goes into museum exhibits, books, and documentaries? One place is government reports. The National VA History Center preserves the history of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers as a predecessor of the modern VA. We do a lot of research related to objects from the Home and we write about what life was like for those who lived and worked there. The Annual Reports that were provided to congress are a great place to look for this information. These reports provide a great deal of information, and you don’t have to travel to an archive, can do it from your computer. See the link at the bottom to access the reports.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 80: LUKE/DEKA Prosthetic Arm

In the 19th century, the federal government left the manufacture and distribution of prosthetic limbs for disabled Veterans to private enterprise. The experience of fighting two world wars in the first half of the 20th century led to a reversal in this policy.

In the interwar era, first the Veterans Bureau and then the Veterans Administration assumed responsibility for providing replacement limbs and medical care to Veterans.

In recent decades, another federal agency, the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA), has joined VA as a supporter of cutting-edge research into artificial limb technology. DARPA’s efforts were spurred by the spike in traumatic injuries resulting from the emergence of improvised explosive devices as the insurgent’s weapon of choice in Iraq in 2003-04.

Out of that effort came the LUKE/DEKA prosthetic limb, named after the main character from "Star Wars."

Featured Stories

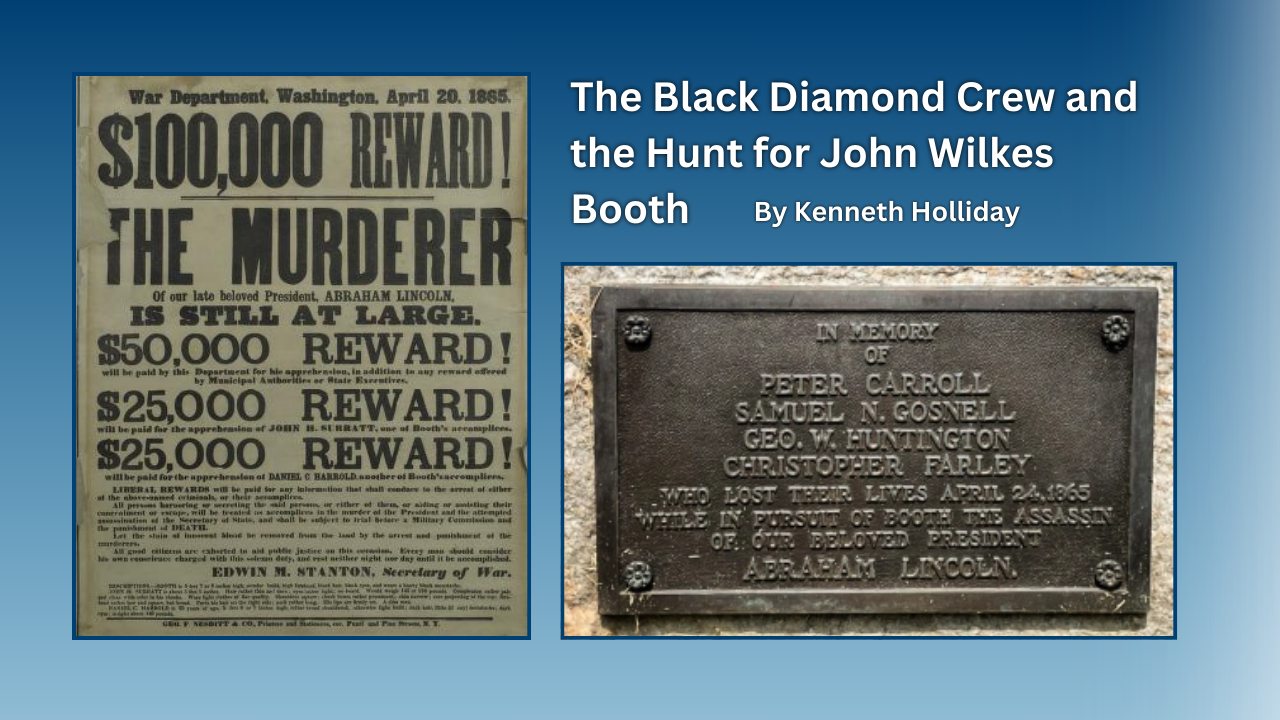

The Black Diamond Crew and the Hunt for John Wilkes Booth

During the late evening, early hours of April 23-24, 1865, the Black Diamond, a ship on the Potomac River searching for President Abraham Lincoln's assassin John Wilkes Booth collided with another ship, the USS Massachusetts. The incident was a terrible accident during the frantic mission to locate the fleeing Booth before he escaped into Virginia. Unfortunately many lives were lost, including four civilians who had been summoned from a local fire department by the Army. For their assistance during this military operation, all four were buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery, some of the few civilians to receive that honor.