In the 19th century, the federal government left the manufacture and distribution of artificial limbs for disabled Veterans to private enterprise. After the Civil War, Union amputees did receive an allowance of $50 to $75 dollars for the purchase of a prosthetic device, along with free transportation to have it fitted. But that was the extent of the government’s involvement. The experience of fighting two world wars in the first half of the 20th century led to a reversal in this policy. During World War I, the Army sent all amputees to Walter Reed General Hospital in Washington, D.C., to be fitted with a government-issued prosthesis and go through rehabilitation.

In the interwar era, first the Veterans Bureau and then the Veterans Administration assumed responsibility for providing replacement limbs and medical care to Veterans. Following World War II, the Veterans Administration also took the lead in promoting research into prosthetics design. Starting in 1948, VA’s newly established Prosthetics and Sensory Aids Service disbursed a million dollars a year to universities and other institutions engaged in this work. In the 1970s, Congress increased the budget for prosthetics research and VA redirected its focus to funding projects conducted by its own investigators at VA medical facilities.

In recent decades, another federal agency, the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA), has joined VA as a supporter of cutting-edge research into artificial limb technology. DARPA’s efforts were spurred by the spike in traumatic injuries resulting from the emergence of improvised explosive devices as the insurgent’s weapon of choice in Iraq in 2003-04. In July 2004, Dr. Brett P. Giroir, the deputy director of the agency’s Defense Sciences Office, testified before Congress of DARPA’s intent to develop “biologically integrated fully functional limb replacements . . . that allow fine motor control” and normal sense of touch.

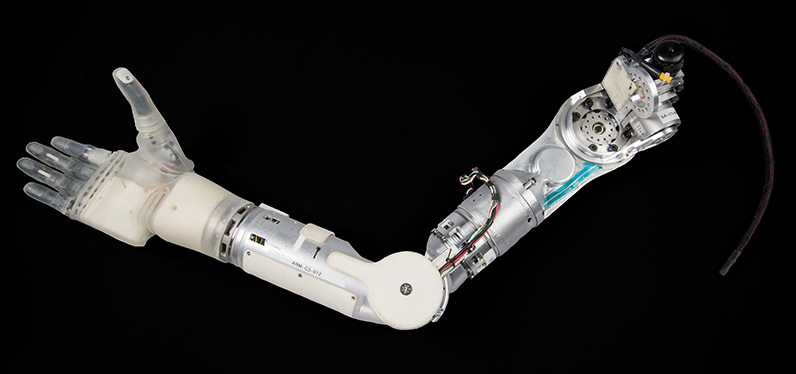

While an arm or leg prosthesis with those capabilities seemed far-fetched at the time, DARPA launched the “Revolutionizing Prosthetics” program a year later to turn that vision into a reality. DARPA invested over $100 million in the program between 2005 and 2018. One of the first initiatives it funded was development of an innovative battery-powered upper arm prosthesis by DEKA Integrated Solution Corporation. DEKA’s design improved on existing prostheses by including a simpler and more flexible control system and a range of pre-programmed grips of varying strength. Another radical feature of the arm was that its joints could be moved simultaneously instead of sequentially.

By 2007, DEKA had completed initial testing of the first two prototypes of the arm. At this point, VA partnered with DAPRA to evaluate the Gen 2 prototype in a wider clinical trial. The VA Rehabilitation Research and Development Service funded an “Optimization Study” under the direction of VA research scientist Linda Resnik. Phase one of the study collected data on amputees wearing the arm in supervised sessions at four VA medical centers and one Army site. Feedback from the trials led to numerous refinements in the software and other aspects of the Gen 2 design. The Gen 3 version of the DEKA arm was ready for the second phase of testing by VA in early 2011. DEKA made several major changes to this iteration of the prosthesis, beginning with the form-fitting rubber sleeve covering the exterior. This gave the arm a much more lifelike appearance than the robotic-looking Gen 2 prototype with its exposed mechanics. Other improvements affected such elements as the user interface, grip strength, hand speed, and the wrist and shoulder joint design.

Eight long years of research and development paid off in May 2014 when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the DEKA arm. Another two years elapsed before a company called Mobius Bionics was formed to produce a commercial version of the limb. The prosthesis was renamed for marketing purposes the LUKE (short for Life Under Kinetic Evolution) arm, a reference to Luke Skywalker who received a bionic replacement for the hand he lost in a duel in the second Star Wars film. Later in 2016, DARPA also finalized an agreement with Walter Reed to supply the artificial arm to the medical center.

On June 30, 2017, DARPA and VA jointly celebrated another milestone in the LUKE/DEKA development story. In a ceremony at the VA New York Harbor Health Care System in Manhattan, Vietnam era Veterans Frederick Downs, Jr., and Artie McAuley became the first amputees to receive the LUKE arm. Downs, who earned a Silver Star and a Bronze Star for Valor in the war, had worked at VA for several decades, serving for a time as the director of its Prosthetic and Sensory Aids Service. During the New York ceremony, the two men showed off their newfound dexterity while wearing the arm, with Downs employing the thumb and index finger grip to peel a banana. Speaking to a reporter prior to the event, Secretary of VA David J. Shulkin called the artificial limb “a life-changer.” He added:

Many people, including our first veterans being fitted today, are still using technology that was 40 years old, which is a hook mounted onto a piece of plastic. Now they can return to doing things like cooking, lifting up suitcases. It gives them a functionality they never had.

Downs put it another way while speaking to the press: “These may seem like very simple, routine things but to someone who can’t do it, to be able to be given this function it’s like magic.”

VA’s and DARPA’s efforts to advance the state of the art in prosthetics design have not ended with the LUKE Arm. Both agencies have continued to support research projects that promise to expand the functionality of artificial limbs even further. If these studies pan out, future versions of the LUKE arm and other prostheses may include yet more revolutionary features, such as the ability to provide sensory feedback and be controlled via electrodes implanted in the body.

By Santos Mencio

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, VA History Office, Department of Veterans Affairs

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.