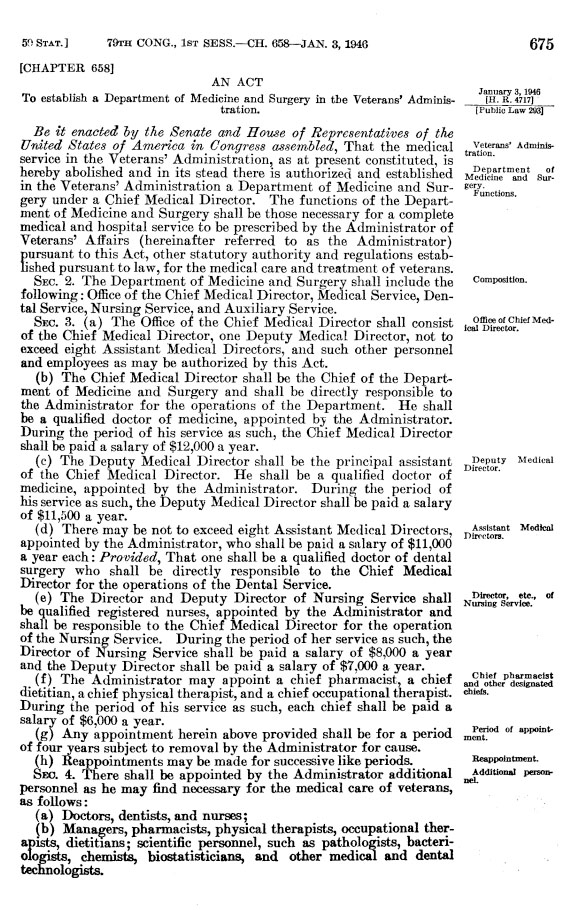

On January 3, 1946, President Harry Truman established the forerunner of today’s Veterans Health Administration when he signed Public Law 79-293, creating the Department of Medicine and Surgery within the Veterans Administration. The bill was the handiwork of three men: General Omar Bradley, the VA Administrator; Dr. Paul Hawley, his chief medical advisor; and Dr. Paul Magnuson, the chair of Northwestern’s Department of Orthopedics. This landmark legislation cemented sweeping changes to Veterans’ health care. The bill exempted medical personnel from the Civil Service hiring regulations, which allowed for doctors and nurses to be selected and appointed more quickly. Additionally, it linked the nation’s medical schools to the VA and initiated a program to construct new VA hospitals.

While the bill was popular with Congress and the public, a last-minute veto push from the U.S. Civil Service Commission threatened to derail its passage. Bradley and Hawley countered the Commission’s objections with their own high-pressure tactics to sway the president. Both threatened to resign on New Year’s Eve if Truman did not sign the legislation. The president chose to side with them and ignore the commission’s entreaties. When the bill became law, Dr. Hawley enthused: “With the signature of the Medical Department Act, our objective is clear, a medical service for the Veteran that is second to none in the world.” He added a promise: “[W]e shall build an outstanding service.”

Equipped with a $500 million budget, Bradley and Hawley set out to make good on that promise and reshape VA health care services. They launched many key initiatives, including the recruitment of 4,000 full-time VA physicians, nurses, technicians, and other medical personnel. They also established the VA Voluntary Service and the Veterans Canteen Service and hired the first 10 female physicians to care for women Veterans. These actions not only improved VA care and increased training opportunities for U.S. physicians but also set the stage for significant growth in VA’s medical research program.

View the Public Law 79-293 (PDF, 5 pages).

By Katie Rories

Historian, Veterans Health Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.

History of VA in 100 Objects

After World War I, claims for disability from discharged soldiers poured into the offices of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the federal agency responsible for evaluating them. By mid-1921, the bureau had awarded some amount of compensation to 337,000 Veterans. But another 258,000 had been denied benefits. Some of the men turned away were suffering from tuberculosis or neuropsychiatric disorders. These Veterans were often rebuffed not because bureau officials doubted the validity or seriousness of their ailments, but for a different reason: they could not prove their conditions were service connected.

Due to the delayed nature of the diseases, which could appear after service was completed, Massachusetts Senator David Walsh and VSOs pursued legislation to assist Veterans with their claims. Eventually this led to the first presumptive conditions for Veteran benefits.