After World War II, the Veterans Administration faced a dire shortage of nurses. During the war, thousands of nurses and doctors left their positions in VA hospitals to join the armed forces. In early 1944 VA Administrator General Frank T. Hines reported a shortfall of roughly 1,000 nurses in 88 of the VA’s 94 hospitals. By the time General Omar Bradley took over as Administrator in late 1945, the deficit had grown to 3,200. With sixteen million Veterans returning home after the war, VA facilities were ill-equipped to handle the massive influx of patients who would need medical care.

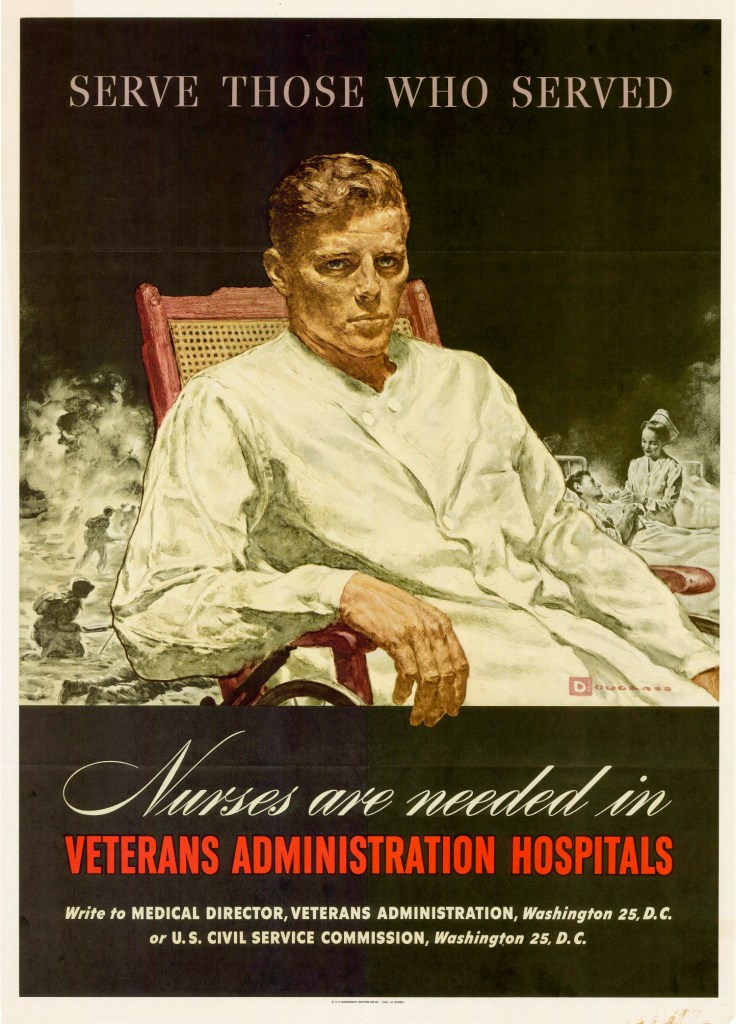

In the closing months of the conflict, VA launched a concerted effort to recruit 2,000 nurses as quickly as possible. Promotional posters made patriotic appeals to nurses, reminding them of the nation’s enduring obligation to care for its Veterans. VA Administrator Hines also reclassified nurses from sub-professional to professional status, increasing their starting salaries and creating an advancement track with four distinct levels, as opposed to two under the old system. Hines hoped that these measures would help VA compete with the Army, Navy, and Public Health Services for nurses.

However, even after the reclassification went into effect, VA’s ability to recruit nurses as well as other medical personnel continued to be hampered by antiquated hiring practices outside the agency’s control. Hiring for Veterans hospitals was not conducted through VA, but through the U.S. Civil Service Commission. The Commission selected nurses who met the requirements for hospitals after a series of exams but based its final hiring decisions on seniority rather than ability. Once chosen, nurses were placed in trial positions in hospitals and were only offered full employment after they completed their probationary assignment. In addition, salaries lagged behind those offered in the private sector and promotions were not merit based.

The act passed by Congress in early 1946 establishing the Department of Medicine and Surgery in VA instituted sweeping changes in the Veteran health care system. Reform of VA’s hiring practices was one of the most impactful. The law removed hiring authority from the Civil Service Commission and empowered VA to hire nurses, doctors, and dentists directly using its own requirements. To further streamline the hiring process, instead of going through the central VA office in Washington, D.C., job candidates could apply by mail or in person at one of thirteen different branch offices around the country.

Under the new system, nurses were offered higher starting salaries with five different pay grades, better living quarters, improved in-service training programs and greater opportunities for post-graduate education. In a 1946 speech to student and graduate nurses attending an event in New York City, Lois E. Gordner, VA’s Assistant Director for Nursing Service, outlined the vision of the agency’s new Chief Medical Director, General Paul R. Hawley, M.D. She explained that Dr. Hawley’s goal was to provide “progressive, professional, and educational advantages to secure the highest type of nurse.”

The VA’s efforts were an immediate success. By May 1946, VA was adding new nurses at a rate of 90 per week. In New York, the VA hospital in the Bronx proved to be such an attractive employer, the New York Times reported in July 1946, that all of its nursing positions were staffed while private hospitals throughout the city were struggling to fill their vacancies. Spokespersons for some of the private hospitals conceded that they could not match VA in terms of salary, hours, or living conditions.

The appointment of VA’s first Chief of Nursing Education in 1950 reflected the growing importance the agency placed on continuing education. Ten years later, VA Administrator Sumner G. Whittier touted the many opportunities for professional development the VA afforded to graduates fresh out of nursing school: “There is plenty of time in VA nursing for learning—for participation in university programs and continuous in-service educational programs, for attendance at workshops and institutes and meetings of professional organizations.” In Sumner’s view, “no other nursing career can exceed that offered by the Veterans’ Administration.” The recovery and rapid expansion of the VA nursing service after World War II is testament to that statement.

By Katie Rories

Historian, Veterans Health Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.