History of VA in 100 Objects

American prisoners of war from World War II, Korea, and Vietnam faced starvation, torture, forced labor, and other abuses at the hands of their captors. For those that returned home, their experiences in captivity often had long-lasting impacts on their physical and mental health. Over the decades, the U.S. government sought to address their specific needs through legislation conferring special benefits on former prisoners of war.

In 1978, five years after the United States withdrew the last of its combat troops from South Vietnam, Congress mandated VA carry out a thorough study of the disability and medical needs of former prisoners of war. In consultation with the Secretary of Defense, VA completed the study in 14 months and published its findings in early 1980. Like previous investigations in the 1950s, the study confirmed that former prisoners of war had higher rates of service-connected disabilities.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.

History of VA in 100 Objects

After World War I, claims for disability from discharged soldiers poured into the offices of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the federal agency responsible for evaluating them. By mid-1921, the bureau had awarded some amount of compensation to 337,000 Veterans. But another 258,000 had been denied benefits. Some of the men turned away were suffering from tuberculosis or neuropsychiatric disorders. These Veterans were often rebuffed not because bureau officials doubted the validity or seriousness of their ailments, but for a different reason: they could not prove their conditions were service connected.

Due to the delayed nature of the diseases, which could appear after service was completed, Massachusetts Senator David Walsh and VSOs pursued legislation to assist Veterans with their claims. Eventually this led to the first presumptive conditions for Veteran benefits.

Exhibits

While Veterans engaged in activities and learned trades at the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (NHDVS) since its inception after the Civil War, formal occupational therapy programs became components of rehabilitative care for Veterans beginning in the 20th century. This exhibit explores what type of activities were used to treat Veterans by showing items from the collection at the National VA History Center.

Featured Stories

In the mid-twentieth century, the lives of Dr. Ivy Brooks and Mildred Dixon, two trailblazing Black women physicians, converged at the Tuskegee, Alabama, VA Medical Center. Doctor's Ivy Roach Brooks and Mildred Kelly Dixon shared much in common. Both women were born in 1916 in the northeastern United States and received training in East Orange, New Jersey. They both launched careers in alternate medical professions before entering the fields of radiology and podiatry, respectively. Pioneering many “firsts” throughout their professional lives, both women faced and overcame the rampant racism and sexism of the era.

History of VA in 100 Objects

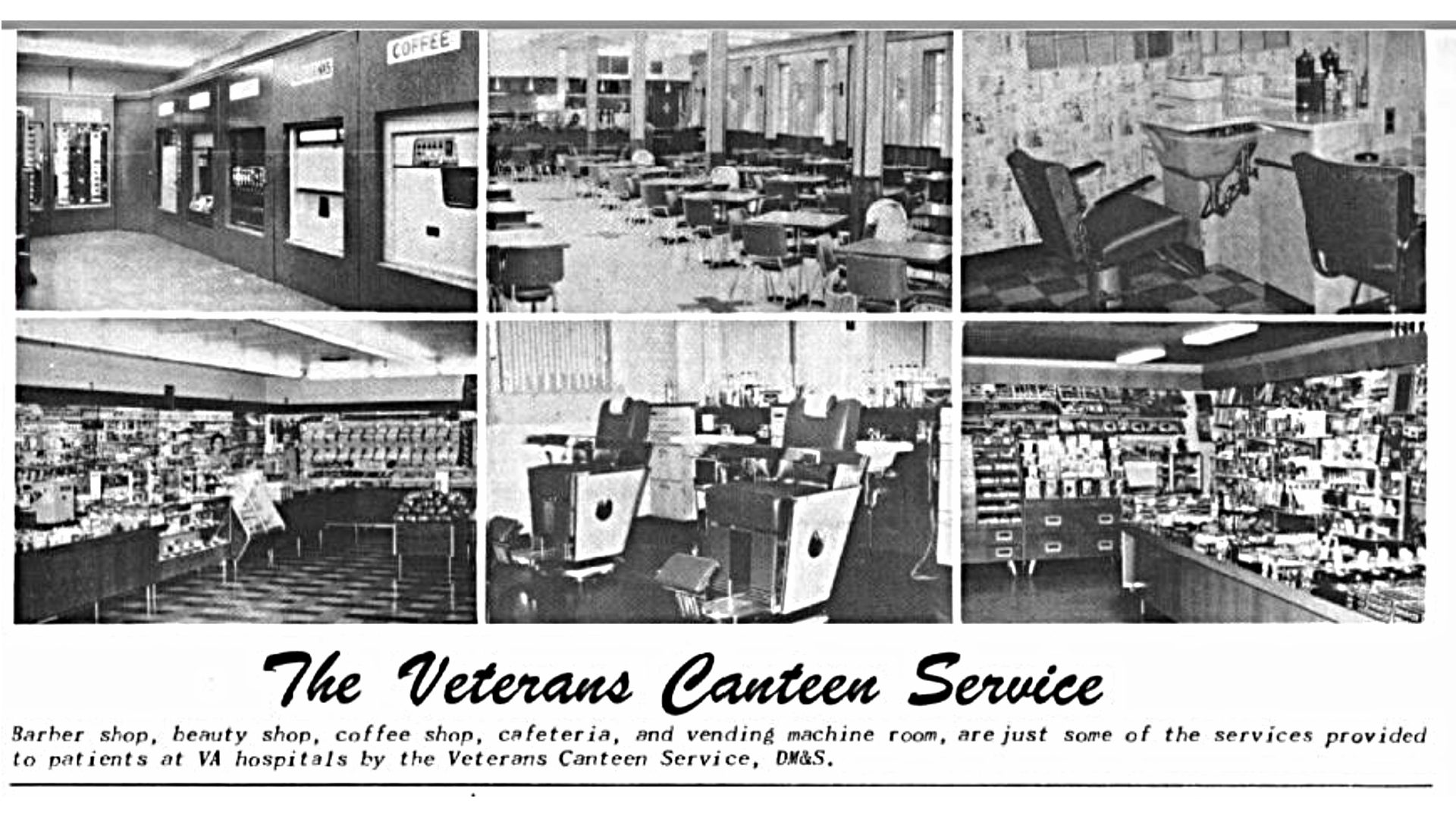

When U.S. Army General Omar N. Bradley became head of VA at the end of World War II, he was determined to improve the quality of care across the agency’s hospital system. His commitment to providing better patient services extended to the stores and canteen service found in VA hospitals. Veterans and advocacy organizations complained that the concessions operated by third-party vendors often charged inflated prices and delivered substandard services.

After VA conducted an internal investigation that validated Veterans’ concerns, Bradley took the issue to Congress. His desire to find a better solution for Veterans led to the establishment of the Veterans Canteen Service.

History of VA in 100 Objects

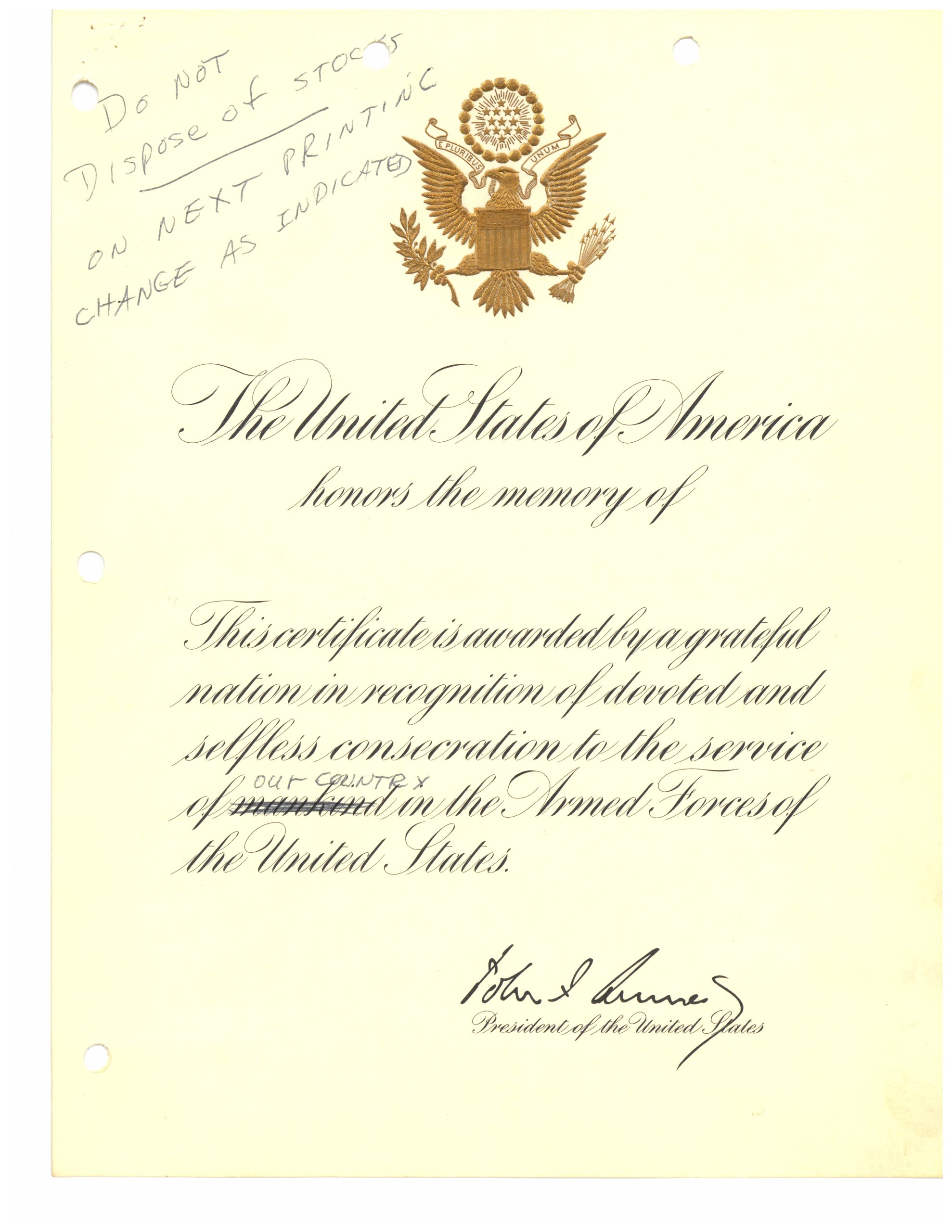

Just after New Year’s Day in 1962, World War II Army Veteran Benjamin B. Belfer sent a letter to his U.S. Senator, Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, suggesting a simple yet powerful way for the government to honor deceased service members. The tradition was for family members to receive the folded American flag that had been draped over the Veteran’s casket during the funeral service. Belfer proposed presenting the next of kin with a memorial certificate signed by the president of the United States in addition to the burial flag. The certificate, he wrote, would be “a keepsake that will never be forgotten by the family and relatives and friends of the departed Veteran.”

After receiving Belfer’s letter Humphrey wasted no time in sharing his idea with the head of the Veterans Administration, John S. Gleason, Jr. Gleason also saw the value in the proposal and in mid-February his staff worked on creating a design for the certificate and wording. On March 6, the certificate was shown to President John F. Kennedy, Jr.. The following day, Kennedy sent Gleason a short note expressing his wholehearted approval. “I think it is an excellent idea, and I believe that the certificate is tastefully and appropriately done,” he wrote, adding that the issuing of certificates should begin “as quickly as possible.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

On July 4, 1948, the Central Blind Rehabilitation Center at the Edward Hines, Jr., VA Hospital in Illinois admitted its first trainee. The Hines Center ushered in a new era of care for blinded Veterans. Yet, its opening was nearly three decades in the making.

Formalized federal care for blinded Veterans dates back to 1917, with the opening of Army General Hospital #7. Later the need to provide rehabilitative services to vision-impaired Veterans returned after World War II.

In 1948, VA opened the Central Blind Rehabilitation Center at the Hines VA Hospital outside of Chicago, Illinois. It's location was chosen because of the large Medical Rehabilitation department already in place was well-suited to provide oversight.

Featured Stories

Dr. Sara (Sadie) Marie Johnson Peterson Delaney was a trailblazer in promoting libraries and literacy – and worked at what would eventually become today’s VA. She was the Chief Librarian of the VA hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama, for 34 years.

Curator Corner

What's in the box? - In the first of many, our National VA History Center is on the search to discover unique collection items one box at a time. On a dark and stormy night (not really), deep in the confines of the quiet halls of the warehouse (actually in a well lit office), our curator staff opened a box to find a mysterious and lonely head, with no body. It was the Curse of the Mannequin Head!

History of VA in 100 Objects

At the VA Medical Center in Dayton, Ohio, Miller Cottage stands as a mostly forgotten reminder of women’s fight for inclusion in the benefits and health care system for Veterans. This long, multi-story brick building with a white-columned portico originated as a barracks built specifically to house female Veterans on the grounds of what was then called the Central Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (NHDVS). The establishment of the residence represented a rare victory for the female Veterans of the First World War in their quest to obtain government support for all uniformed women who served and sacrificed during that conflict.

History of VA in 100 Objects

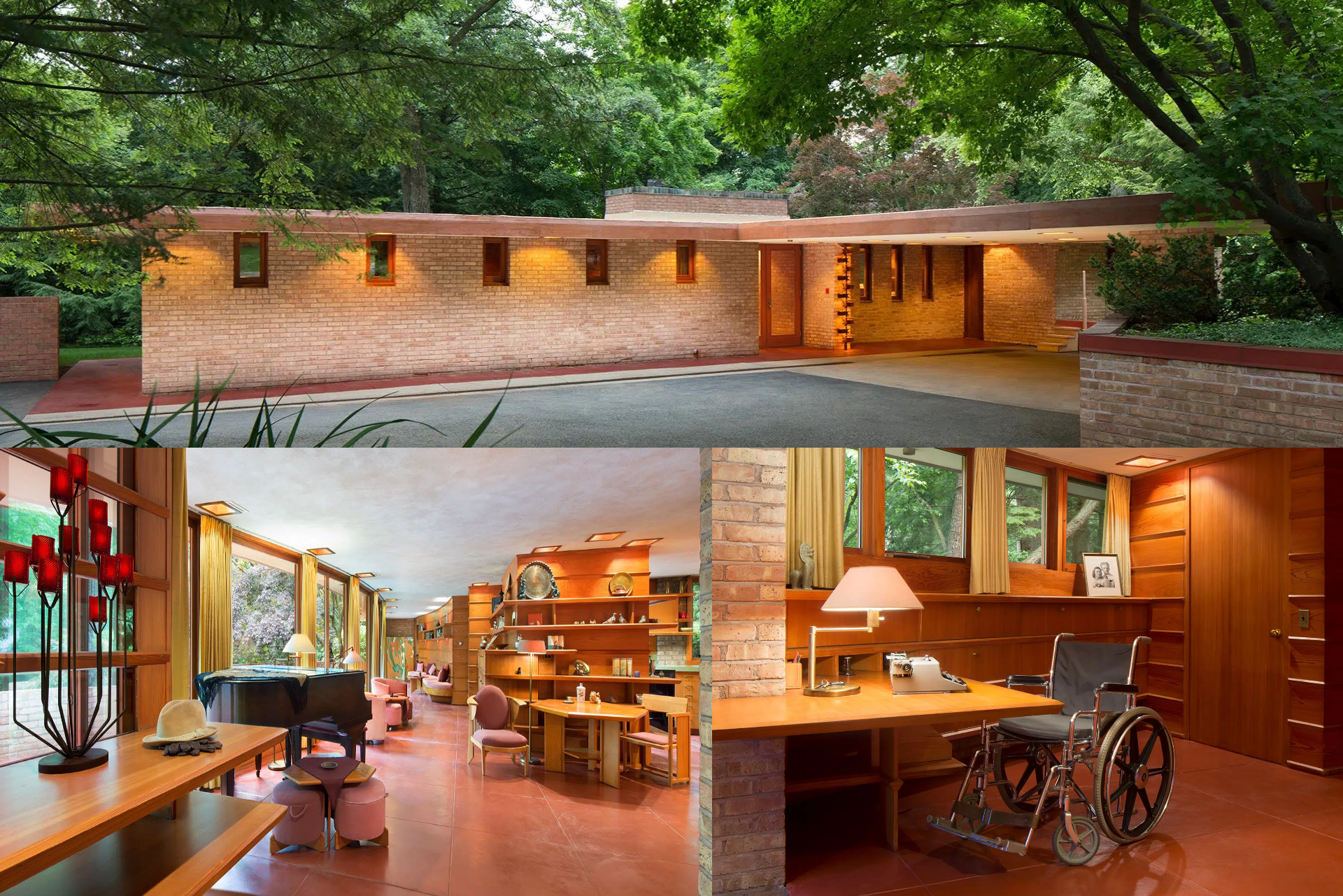

When the GI Bill became law in 1944, it included a home loan program for Veterans. After several changes to update the law to reflect current market prices and challenges, one area still needed addressed: support for Veterans who were dependent on wheelchairs for mobility. The answer was the Specially Adapted Housing program, and one of the earliest homes built with the grant money was designed by acclaimed builder Frank Lloyd Wright.