After the GI Bill became law in 1944, Veterans struggled at first to take advantage of the home loan provisions. This part of the bill was intended to help returning service members purchase a home by guaranteeing 50 percent of their mortgage. However, the law capped the guaranty at $2,000, an amount that was too small to be useful at a time when the high demand for the nation’s limited supply of housing sent real estate prices soaring.

Additionally, the loan had to be paid off within 20 years, leading to monthly mortgage payments that were beyond what many Veterans could afford. In late 1945, Congress revised the law, doubling the guaranty to $4,000 and extending the mortgage period to 25 years. Thanks to these changes and improvements in the housing market, almost a million Veterans were able to secure a VA-backed loan in 1946-47.

Even after Congress addressed the shortcomings in the loan program, however, home ownership remained too expensive a proposition for one cohort of Veterans—those with permanent disabilities that left them dependent on a wheelchair for mobility. The VA estimated that it had roughly 2,400 World War II Veterans in its care that were paralyzed from the waist down due to spinal cord injuries. An indeterminate number of Veterans with other kinds of wartime wounds were likewise reliant on wheelchairs. Many of these service members remained in VA or military hospitals after the war, in part because they lacked housing that could accommodate their disability.

In 1947, Congress turned its attention to addressing the needs of this group. During the summer, the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs held hearings on several bills that would provide some form of assistance to Veterans in wheelchairs who required special housing. In July, the committee approved a measure proposed by Illinois Representative and World War I Veteran Richard B. Vail. His bill would entitle Veterans with qualifying disabilities to a government grant of up to $10,000 to cover 50 percent of the costs of buying a new home or remodeling an existing one.

The bill passed the House, but not until the spring of 1948. Afterwards, it was referred to the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency, which convened its own hearing on the legislation. During the hearing, a paraplegic Veteran named David Reiniger delivered a simple but powerful statement in support of the bill:

The ordinary house has doorways that are too narrow. Bathroom fixtures are not adaptable to us. We need ramps to enter the house, . . . We need the rooms all on one floor: yes. And a house of that type costs a lot more money than the ordinary house. . . . Now this bill . . . would make it possible for most us to afford a house of that type.

At the same session, representatives from the Veterans of Foreign Wars, Disabled American Veterans, Paralyzed Veterans Association of America, and other Veterans organizations all endorsed the measure. The Banking and Currency Committee reported favorably on the bill, noting that the government stood to save money in the long run. A disabled Veteran requiring hospitalization in a VA facility cost the government on average over $7,000 a year. But “if a substantial number of such patients can be released to their own homes, the net long-range financial saving to the Government would be very large,” the committee concluded. The bill became law in June 1948.

In the first nine years of the Specially Adapted Housing (SAH) program, around 6,500 World War II and Korean War Veterans used the grant money to acquire a wheelchair-accessible home. According to a New York Times report, this number represented about 90 percent of the disabled service members who were eligible for the funding. One Veteran who benefited from the program in a unique way was Kenneth Laurent.

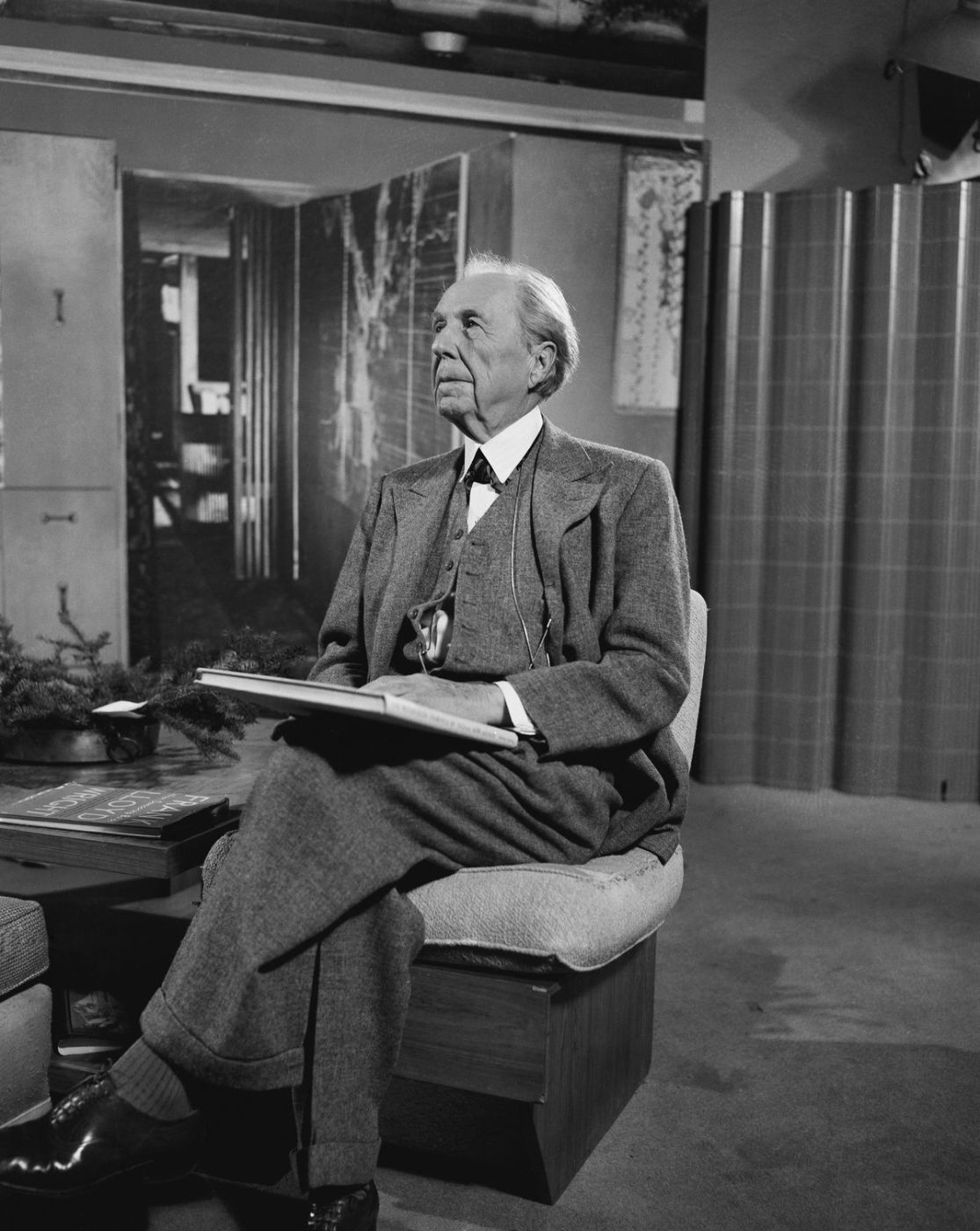

Following his service in the Navy during World War II, Laurent was left paralyzed when surgeons removed a tumor on his spinal cord in 1946. While recuperating in a VA hospital, Laurent contracted with Frank Lloyd Wright to build a house for him and his wife Phyllis in their hometown of Rockford, Illinois.

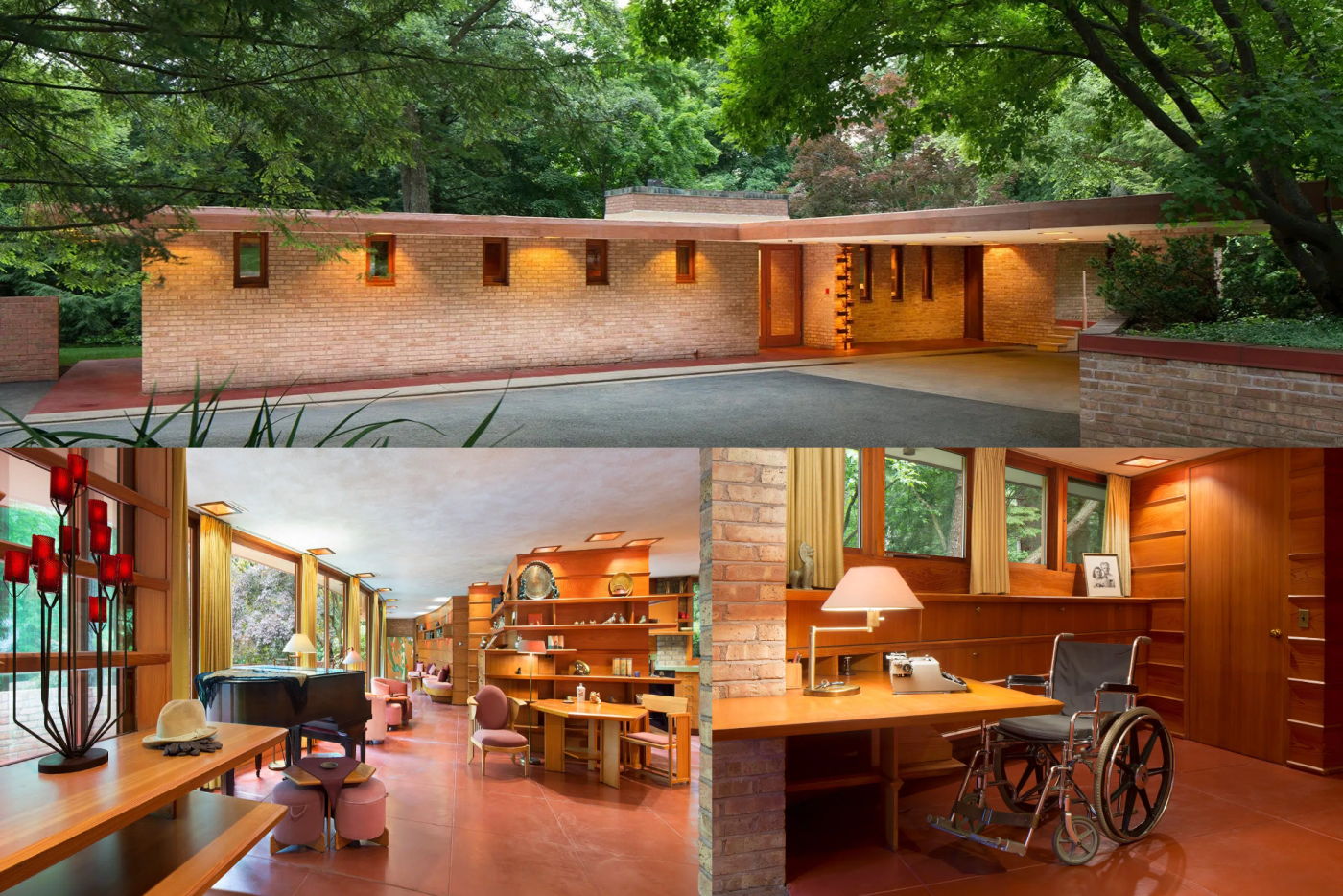

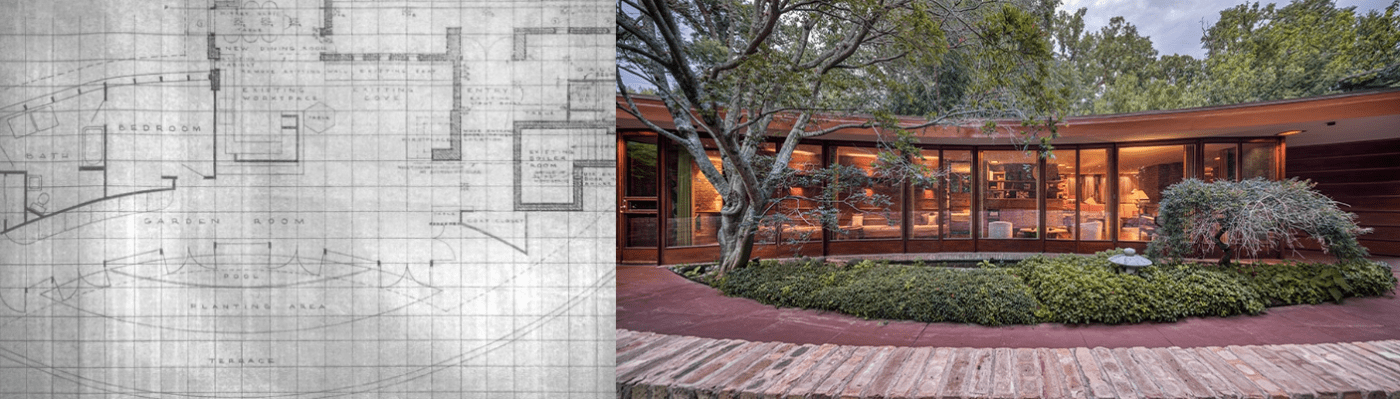

The one-story residence Wright designed featured many of the famed architect’s signature touches—an open floor plan, built-in furnishings, banks of tall windows to admit the natural light, and radiant heat in the flooring.

The Rockford house was one of more than 100 homes Wright built in this style. Yet, he also customized the home to make it wheelchair friendly. The extra-wide doorways, oversized shower stall, cabinets with hinged doors and drawers, lower-than-normal-height light switches, doorknobs, and bathroom fixtures, and other modifications combined to create a living space that allowed Laurent to surmount his physical limitations. He would later say about the house that it “helped me to focus on my capabilities, not my disability. That is the true gift that Mr. Wright gave to me.”

Since its beginnings in 1948, the SAH program has enabled almost 50,000 Veterans to live independently in housing that has been modified to meet their needs. Over the intervening years, Congress has amended the law several times, increasing the size of the grants and expanding eligibility to include certain degenerative diseases and other medical conditions. For Kenneth and Phyllis Laurent, the house in Rockford, Illinois, that Frank Lloyd Wright built for them with SAH funding after World War II became their lasting home. They raised a family there and lived in the house for six decades, until their passing in 2012. In 2014, it was turned into a museum.

By Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D.

Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.