In photos with her fellow politicians, she often appears as the only woman in the frame. Yet, Edith Nourse Rogers never hesitated to speak up on the issues that mattered most to her. She dedicated much of her time in office to supporting Veterans and advocating for their welfare. She also fought with great success to elevate the status of women within the military. Rogers adopted the military motto “Fight hard, fight fair, and persevere” as her own and that mindset served her well as she navigated the male-dominated corridors of power during a trailblazing political career that spanned 35 years and 18 consecutive sessions of Congress.

Born in 1881 into an established New England family, Rogers enjoyed a refined upbringing. Her father managed a textile mill in Lowell, Massachusetts, and her mother immersed herself in volunteer social work at the family’s church. Edith often accompanied her mother, providing aid to those in need. A young Edith was tutored privately before attending boarding school and then finishing school in Paris. In 1907 she married lawyer John Rogers, who in 1912 was elected as a Republican to the House of Representatives for Massachusetts’s Fifth District. When John served on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Edith traveled with him to the United Kingdom and France during World War I.

Rogers’s volunteer experience proved invaluable. In both England and France, she served in the Red Cross, tending injured soldiers. From her “boots on the ground” vantage point, Rogers kept President Woodrow Wilson apprised of the medical treatment American servicemen were receiving overseas. Upon returning to the United States, she joined the newly founded American Legion as part of its women’s auxiliary. Rogers continued her service to Veterans in Washington, D.C. as a Gray Lady for the American Red Cross and was dubbed the “Angel of Walter Reed Hospital.” Her early interactions with military personnel shaped the course of her later political career and dictated the causes that would become her life’s mission.

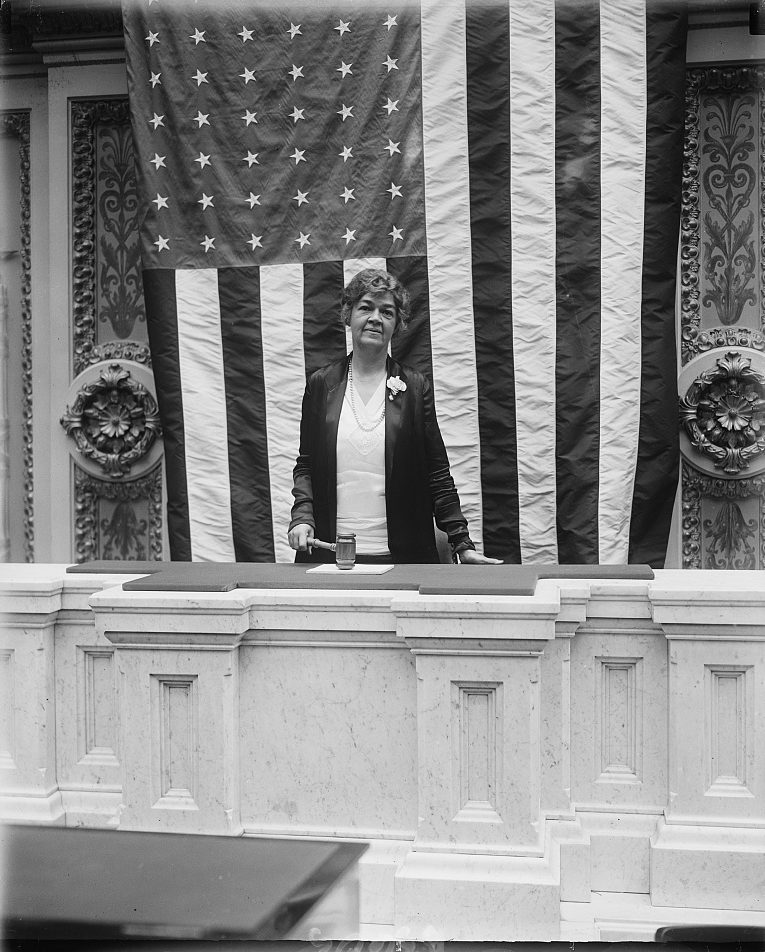

Her husband’s untimely death in 1925 launched Rogers’ life in a new direction. Although women had gained the right to vote a mere five years earlier and a grand total of six had been elected to Congress, Rogers decided to run for her late husband’s seat. She won the special election in a landslide, beating her Democratic opponent, former mayor Eugene Foss, with 72 percent of the vote. During her first year in office, Rogers made her voice heard, sponsoring a bill that created a permanent U.S. Army Nurse Corps.

The following year, she supported legislation establishing pensions for Army nurses who served in the war and disability payments for those who sustained injuries in the line of duty. Rogers also secured an assignment on and soon chaired the newly established Committee on World War Veterans’ Legislation, thus beginning her decades’ long commitment to advancing the welfare of Veterans. During the second half of the decade, Rogers and other committee members oversaw the appropriation of millions of dollars for the construction of veterans hospitals. In 1930, she supported the Veterans’ Administration Act, which consolidated all of the government offices responsible for Veterans benefits and medical care into a single federal agency.

In the years preceding World War II, Rogers was one of the first politicians to condemn Adolf Hitler and anti-Semitism. She spoke candidly about the treatment of European Jews and encouraged government officials to accept refugee ships. In 1939, she co-sponsored a bill with Robert F. Wagner, the Democratic Senator from New York, that would have allowed upwards of 20,000 Jews, age 14 and under, into the country. The Wagner-Rogers bill unfortunately failed, with tragic results.

In 1941, Rogers launched a new legislative effort that would have great ramifications for future generations of women. On May 28, she introduced a bill to establish a women’s corps within the Army independent of the Nurse Corps. After much heated debate and several amendments, her bill passed almost a year later, on May 14, 1942.

The law creating the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) compromised her vision, as women serving in the WAAC were not granted military status, thus depriving them of life insurance and other benefits given to male soldiers. Nonetheless, WAACs performed a variety of essential jobs for the Army and proved so indispensable that military leaders dropped their opposition to allowing women to serve in the Army on the same general terms as men.

Rogers had the satisfaction of sponsoring a new bill establishing the Women’s Army Corps that became law in mid-1943. Overall, about 150,000 women served in the WAAC and WAC and they were employed in every major theater of operations during the war. The WAC was largely demobilized by 1946, but two years later, President Harry S. Truman signed the Women’s Armed Services Act, which allowed women to enlist in all branches of the armed forces. This measure fulfilled Rogers’ ambition of securing for women the same right and opportunity to serve their country as men.

During the war, Rogers made an enduring contribution to the other cause dear to her heart: the well-being of Veterans. After World War I, Rogers had seen the difficulties many Veterans experienced when they left the military. She wanted to spare the millions currently in uniform from similar hardships and do everything in her power to ease their return to civilian life.

As the ranking Republican on the Veterans’ Legislation Committee, she joined with chair John Rankin, a Democrat from Mississippi, to take up a legislative proposal for a G.I. Bill of Rights submitted by the American Legion in early 1944. Her work on and support for the bill helped secure its passage in Congress. In its final form, this landmark piece of legislation provided ex-service members with a package of benefits never before offered to Veterans: unemployment compensation, money for education and training, and low-interest loan guarantees to purchase a house, business, or farm.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt invited Rogers to the historic bill-signing ceremony held on June 22, 1944. She was given a place of prominence just behind him and, in recognition of her efforts on behalf of the bill, Roosevelt handed his pen to Rogers after he signed it.

In the post-war era, Rogers continued to serve as a powerful advocate for Veterans. During the Korean War, she played a key role in getting Congress to approve a new version of the G.I. Bill granting educational and loan benefits to Veterans of that conflict. She also endorsed turning the Veterans Administration into a cabinet-level agency, an idea that would not become a reality until President Ronald W. Reagan came out in support of such a measure more than three decades later.

Rogers was not always on the right side of history. She protested some New Deal policies, and, in the 1950s, she supported Joseph McCarthy’s House Committee on Un-American Activities that impinged upon citizens’ civil liberties. Rogers also railed against the inclusion of communist China into the United Nations. Rogers did, however, oppose child labor and she supported Civil Rights legislation.

Although she advocated for women’s causes, Rogers would not have considered herself a feminist. She believed a woman’s primary duty was to her family. In fact, early in her career, she voted to limit women’s employment to forty-eight hours per week. But as a child-free progressive and careerist, she championed women who chose to serve in the military like no other politician of her time.

Throughout her political career, Rogers sponsored more than 1,200 bills, nearly half of which concerned Veterans’ issues, and she continued fighting on their behalf from her seat in Congress until the day she died in 1960 at age 79. She received many honors both during her lifetime and afterwards. Rogers was the first woman to receive the American Legion’s Distinguished Service Cross.

In 1978, on the fiftieth anniversary of its opening, the VA medical center in Bedford, Massachusetts, was renamed the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital. Twenty years later, Rogers was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Most recently, VA celebrated her name and work by establishing the Edith Nourse Rogers STEM Scholarship, which provides an additional $30,000 for specialized training to Veterans who have exhausted their educational benefits. Her decades of public service and dedication to improving the lives of Veterans remain her most inspiring legacy today.

By Maureen Thompson

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."