“Freedom has never been free.”1

Medgar Evers, June 7, 1963

Medgar Wiley Evers (July 2, 1925 – June 12, 1963) lived by these words as a champion of Black Civil Rights in the mid twentieth century. His mission to change racial discrimination in America was fueled by his upbringing and tenure in the military.

Evers was the third child of James and Jesse Evers, born in Decatur, Mississippi, during the era of Jim Crow.2 Evers excelled in school despite the segregated system in which Black public schools in the South lacked proper funding for teachers, classrooms equipment, textbooks, or bus transportation. The lack of school buses forced Evers and his siblings to walk miles to school and exposed the Evers children to regular verbal racial epithets, being spit on, and being struck by objects thrown by White students riding on buses. Evers’ youth was shaped by other injustices. When he was 14, a friend of his father was dragged behind a wagon, shot, and lynched for allegedly insulting a White woman.3 His bloody clothes were purposefully on display on a fence for months as a lesson to the Black community.

Military Service

Evers enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1943 at the age of 17 during World War II, prompted by the racism he experienced at home, and his brother Charles’s enlistment the year before. He served with the segregated 657th Port Company, part of the Red Ball Express that gained fame for delivering desperately needed food, ammunition, and oil to troops at the front.

During his time on the European front, Evers was troubled by the segregation and mistreatment of Black troops. French Black servicemen were treated with equality, unlike their American counterparts. Evers prophetically told his brother Charles, “When we get out of the Army, we’re going to straighten this thing out!”4

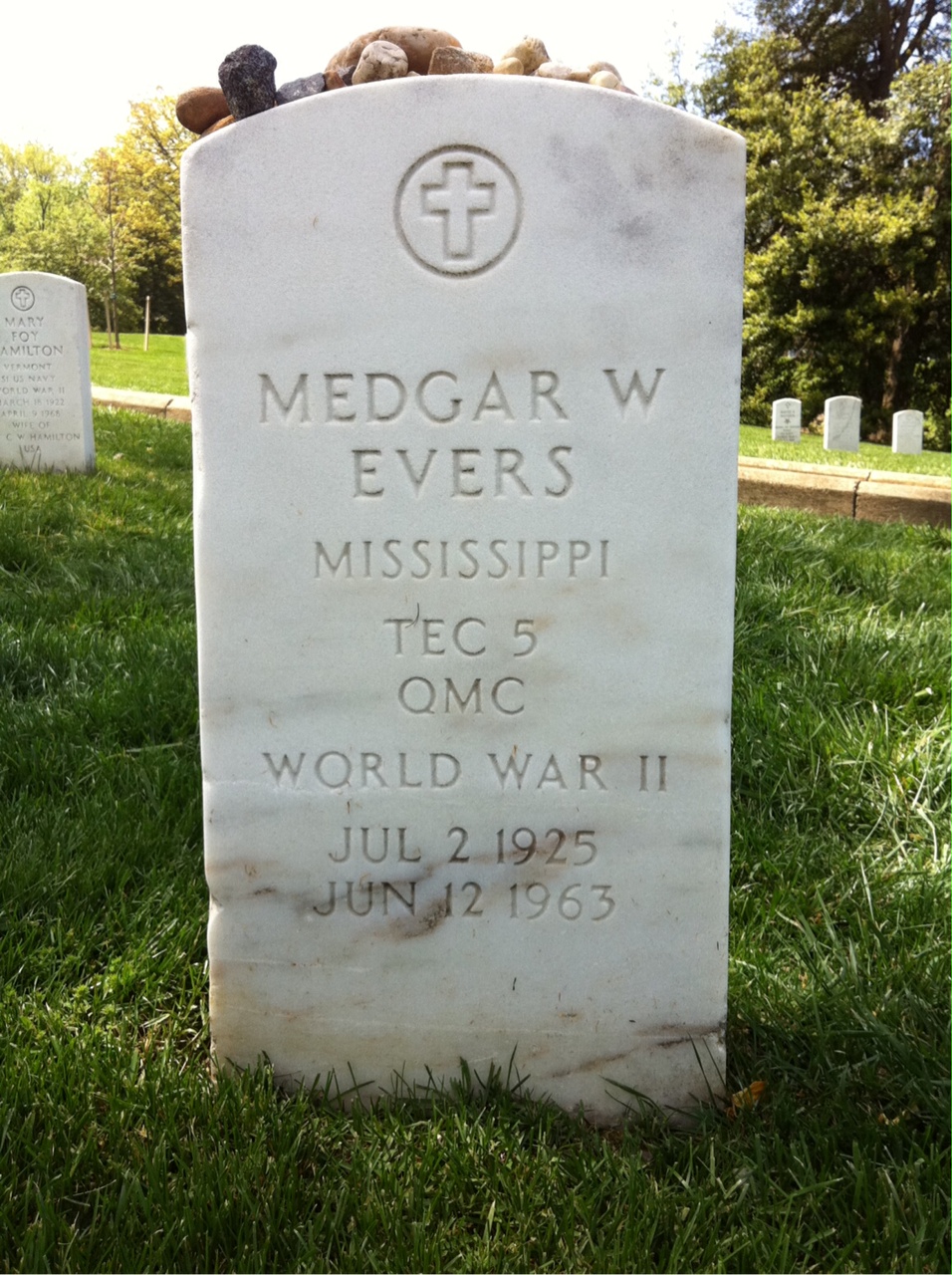

Evers was honorably discharged in 1946 with the rank of a Technician Fifth Grade (corporal equivalent).5 Due to his participation in the Operation Overlord landings at Normandy on D-Day and other combat locations throughout the European front, he earned a Good Conduct Medal, European – African – Middle Eastern Campaign Medal (two Bronze Service Stars, Normandy and Northern France Campaigns), and the World War II Victory Medal.

Returning Home

Evers and Charles returned home to Decatur after the war. In spring 1946 they led a group of Black Veterans to register to vote at the Newton County courthouse, where they were met by angry armed White men who threatened violence if they did not leave. This, along with continued racial strife and a lack of job opportunities, persuaded Evers to continue his education in hopes of a building better future in Mississippi.

Using his GI Bill benefits, in 1948 he enrolled at Alcorn Agriculture and Mechanical College in Mississippi (now Alcorn State University). Evers excelled in business administration, joined the debate team, ran track, and played football. “By his senior year he had become editor of the Alcorn Yearbook, the student newspaper, the Alcorn Herald, and was named to Who’s Who Among American College Students.”6

Post College

Evers married classmate Myrlie Beasley in 1951 and moved to Mound Bayou, Mississippi, after graduating from Alcorn in 1952. During this time, he served as the president of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership and led boycotts of gas stations denying Blacks use of their restrooms. After the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education found school segregation unconstitutional, Evers became the first Black person to apply to the University of Mississippi’s law school. When the university denied his admission based on a technicality, he asked the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for legal assistance.

Although his attempt at law school admittance ultimately failed, NAACP Mississippi State Conference leader E. J. Stringer was impressed by Evers’ eloquence, focus, resolve, and leadership. He offered him a position as the first field secretary for Mississippi. Evers accepted the position and feverishly worked to facilitate change in the state.

NAACP Tenure

During his field secretary tenure, Evers led nine murder investigations, including the 1955 murder of Emmett Till. Evers and his team secretly sought and found Black witnesses to testify, kept them in protective custody, and safely spirited them out of town after the trial. For one witness, Evers collaborated with a mortuary to hide a witness in a casket, and drove him “out of town, out of the state, across the border, to Tennessee, and then north.”7

A few years later, Evers helped a friend and U.S. Air Force Veteran James Meredith enroll and desegregate the University of Mississippi. Evers was instrumental in securing the NAACP’s legal team, led by Thurgood Marshall, for Meredith’s case. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Meredith, and he became the first Black student at the University of Mississippi on October 2, 1962.

Assassination

In May 1963, Evers publicly challenged the mayor of Jackson, Mississippi’s racist actions. Appearing on local TV station WLBT, Evers stated, “The years of change are upon us. In the racial picture things will never be as they once were. History has reached a turning point, here and over the world.”

The next month, Evers was returning home from an activist meeting shortly after midnight. Walking up his driveway, he was shot in the back by World War II Marine Corps veteran and White supremacist Byron De La Beckwith.8 He died in the hospital less than an hour later.

Evers’ funeral was attended by thousands of people including Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King. He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery and is survived by his wife, Myrlie, and their three children. His death, the first murder of a nationally significant leader of the American Civil Rights Movement, heightened public awareness of civil rights issues and became a catalyst for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Posthumous Honors

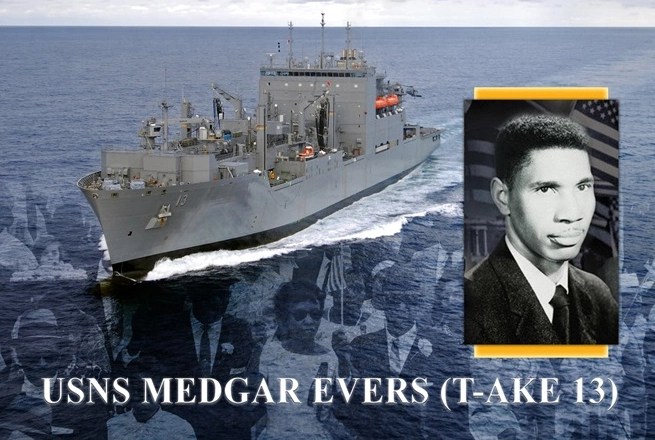

Long after his tragic death, Evers and his Civil Rights work continues to be honored. In 1969, Medgar Evers College was established in Brooklyn, New York, as part of the city university system. In 1992, the Mississippi capital of Jackson dedicated a life-size bronze statue of Evers, and in December 2004 renamed the airport as Jackson–Medgar Wiley Evers International. In 2011, the U.S. Navy honored Evers with the launch of a dry-cargo ammunition ship, the USNS Medgar Evers (T-AKE-13). In June 2013, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of his death, Alcorn State University erected a statue of Evers on campus. His Jackson house was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 2016; and in December 2020 the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home National Monument was established as a unit of the National Park Service, part of the African American Civil Rights Network.9

Medgar W. Evers’ unrelenting perseverance, dedication to duty, and sacrifice for racial equality, and freedom reflected the highest values of our democracy and the U.S. military service.

Footnotes

- Bell, T. “Army Veteran Medgar Wiley Evers a Foot Soldier in Struggle for Justice.” www.army.mil, February 25, 2020. ↩︎

- “Hearings before the United States Commission on Civil Rights: Hearings Held in Jackson, MI FEB 16-20 1965.” Google Books. Google. Accessed February 7, 2022. ↩︎

- Davis / October 2003, Dernoral. “Medgar Evers and the Origin of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi.” Mississippi Historical Society, October 2003. ↩︎

- “Medgar W. Evers.” National Museum of the United States Army. Accessed February 7, 2022. ↩︎

- “Civil Rights Activist Medgar Evers.” Naval History and Heritage Command, January 31, 2020. ↩︎

- Davis, Denoral. “Medgar Evers and the Origin of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi.” Medgar Evers and the Origin of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi – 2003-10. Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Accessed February 7, 2022. ↩︎

- “Eyes on the Prize: Interview with Myrlie Evers.” Home – Washington University Digital Gateway. Washington University in St. Louis. Accessed February 7, 2022. ↩︎

- “Medgar W. Evers.” National Museum of the United States Army. Accessed February 7, 2022. ↩︎

- “Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home National Monument.” National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, February 1, 2022. ↩︎

By Tess Jackson

VA History Office Program Specialist

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

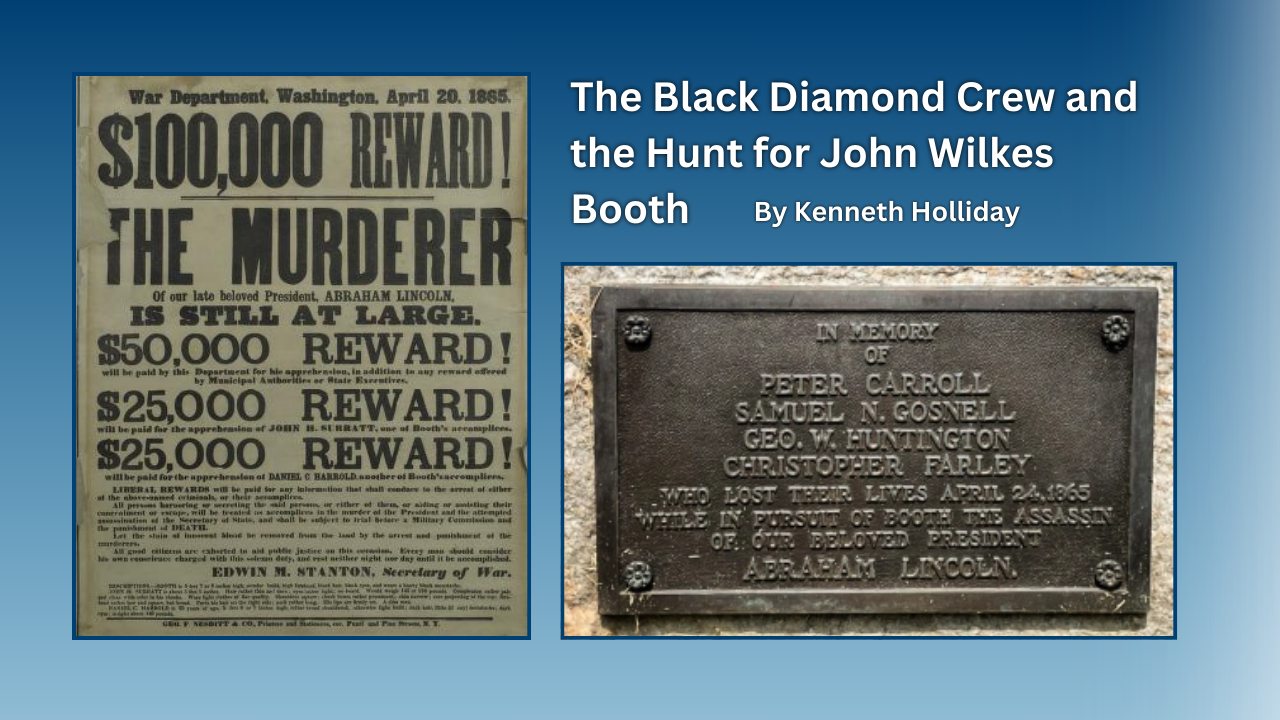

During the late evening, early hours of April 23-24, 1865, the Black Diamond, a ship on the Potomac River searching for President Abraham Lincoln's assassin John Wilkes Booth collided with another ship, the USS Massachusetts. The incident was a terrible accident during the frantic mission to locate the fleeing Booth before he escaped into Virginia. Unfortunately many lives were lost, including four civilians who had been summoned from a local fire department by the Army. For their assistance during this military operation, all four were buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery, some of the few civilians to receive that honor.

Featured Stories

In the mid-twentieth century, the lives of Dr. Ivy Brooks and Mildred Dixon, two trailblazing Black women physicians, converged at the Tuskegee, Alabama, VA Medical Center. Doctor's Ivy Roach Brooks and Mildred Kelly Dixon shared much in common. Both women were born in 1916 in the northeastern United States and received training in East Orange, New Jersey. They both launched careers in alternate medical professions before entering the fields of radiology and podiatry, respectively. Pioneering many “firsts” throughout their professional lives, both women faced and overcame the rampant racism and sexism of the era.

Featured Stories

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, American Expeditionary Force commander General John J. Pershing requested the recruitment of women telephone operators that were bi-lingual in English and French. Eventually 233 were selected out of over 10,000 applicants, and they served honorably through the war, earning the nickname of 'Hello Girls.'

However, their employment was not officially recognized as military service and therefore were neither honorably discharged, or eligible for the benefits other returning Veterans would receive. This kicked off a 60-year fight for 'Hello Girls' to receive legal Veteran status.