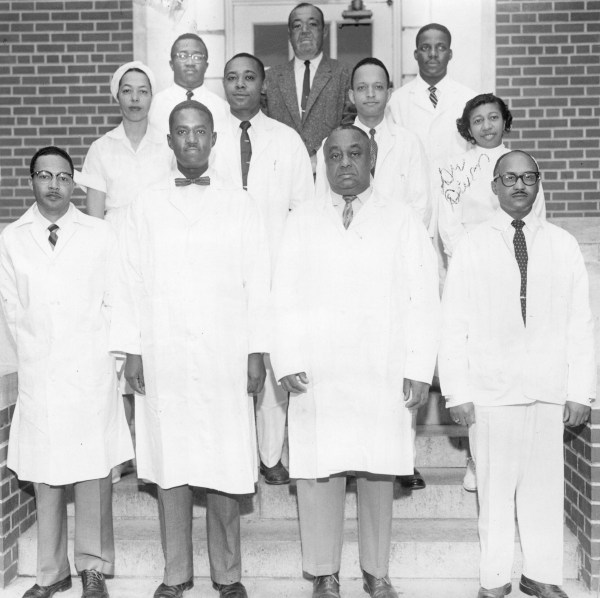

Both Brooks and Dixon were physicians at the Tuskegee VA Medical Center

In the mid-twentieth century, the lives of two trailblazing Black women physicians converged at the Tuskegee, Alabama, VA Medical Center. Doctors Ivy Roach Brooks and Mildred Kelly Dixon shared much in common. Both women were born in 1916 in the northeastern United States and received training in East Orange, New Jersey. They both launched careers in alternate medical professions before entering the fields of radiology and podiatry, respectively. Pioneering many “firsts” throughout their professional lives, both women faced and overcame the racism and sexism of the era.

Ivy Ophelia Roach Brooks was born June 21, 1916, in Brooklyn, New York. Brooks graduated from Hunter College in 1940 and worked as a dietician at Harlem Hospital while earning her Master of Science degree from Columbia University. After graduating Columbia in 1944, Brooks promptly enlisted in the Women’s Army Corps where she worked as a dietician in an Army hospital during World War II. Between 1947 and 1950, she taught nutrition and diet therapy courses to nursing students at the John A. Andrew Hospital at Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University). Brooks took advantage of the G.I. Bill, enrolling at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, where, in 1954, she graduated with her M.D. degree.

The following year, Brooks was hired by the Tuskegee VA Medical Center where she was trained in diagnostic radiology. She was sent to the VA hospital in East Orange, New Jersey, to learn state-of-the-art techniques. In 1966, Brooks was named director of radiology at Tuskegee, a position in which she served until 1986. During her tenure, she served as Secretary of the board of the National Medical Association Section on Radiology. Brooks’ husband, Alfred, also worked at the Tuskegee and the couple raised three children together. Brooks died in 1986 following a battle with cancer. She is remembered as the first recognized Black female leader in radiology and the first Black woman to complete training in radiation oncology.

Mildred Kelly Dixon was born on November 2, 1916, in Philadelphia, PA, but was raised in East Orange, New Jersey. After graduating from dental nursing school in East Orange, she worked for a dentist named Dr. Gilborn in Montclair, New Jersey. Recognizing Dixon’s potential, Gilborn introduced her to a local podiatrist named Dr. Helen Hawthorne, who encouraged her to apply to medical school. Dixon exited dental health to attend the Ohio College of Chiropody, today’s Kent State University College of Podiatric Medicine. After graduating in 1944, Dixon was hired as Dean of Women at Tuskegee Institute where she met her future husband, a professor named James O. Dixon. The couple married and they parented two children together.

Dixon pursued her podiatric career but faced obstacles. She was denied licensure by the Alabama Association of Chiropodists, an issue affecting numerous Black physicians, particularly those in the South. In 1949, when Dixon petitioned the National Association of Chiropodists, the organization granted Dixon a lifetime membership, which permitted her to practice in the state of Alabama.

In 1957, Dixon was hired by the Tuskegee VA as the first full-time African American female podiatrist. There, in 1976, Dixon established Alabama’s first podiatric residency program. Other “firsts” Dixon accomplished include becoming the first African American woman president of the Association of Podiatrists in Federal Service and the National Podiatric Medical Association and as both the first woman and first African American inducted into the Ohio College of Podiatric Medicine Hall of Fame. In 2000, she was also inducted into Alabama Senior Citizens Hall of Fame.

When Dixon retired in 1985, after almost 30 years as the chief of podiatry, she continued to serve the public as an AARP representative and a National Park Service volunteer at the George Washington Carver Museum on the Tuskegee University campus. When both Dixon and the National Park Service turned one hundred years-old in 2016, a local event celebrated the two. Dixon died in 2018 at 102 years of age but her legacy continues through the Dr. Mildred Dixon Endowed Scholarship for Podiatric Medicine.

In many aspects, the lives of both Brooks and Dixon paralleled one another. Their initial forays in nutrition and dental health led to medical careers in radiology and podiatry, where they excelled as the first African American women in their fields. These pioneering women illustrate how their determination to become physicians overcame the obstacles inherent in mid-twentieth century culture. Both served as role models for future generations of young women aspiring to careers in medicine.

Sources:

- Meharry Medical School Records.

- “In Memoriam,” Alan E. Oestreich, 1987. Ivy O. Brooks, M.D | Radiology (rsna.org)

- “How We Got Here: The Legacy of Anti-Black Discrimination in Radiology,” Julia E. Goldberg et al, 2023. How We Got Here: The Legacy of Anti-Black Discrimination in Radiology | RadioGraphics (rsna.org)

- “Reflections On Black History in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery,” Alton R. Johnson, DPM, 2022. Black History In Podiatric Medicine And Surgery (hmpgloballearningnetwork.com)

- “100-year-old retired podiatrist continues to serve the public.” VA News, 2016. 100-year-old retired VA podiatrist continues to serve the public – VA News

- Kent State, Alumni Life, 2007. https://www.kent.edu/philanthropy/news/dixon-lifetime-spent-blazing-trails-minorities

- “KSUCPM Remembers Mildred K. Dixon, DPM; A Trailblazer for Women, Minorities, and her Profession,” 2018. KSUCPM Remembers Mildred K. Dixon, DPM; a Trailblazer for Women, Minorities, and her Profession | Kent State University

By Maureen Thompson, Ph.D.

Historian, Central Alabama Veterans Health Care System

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

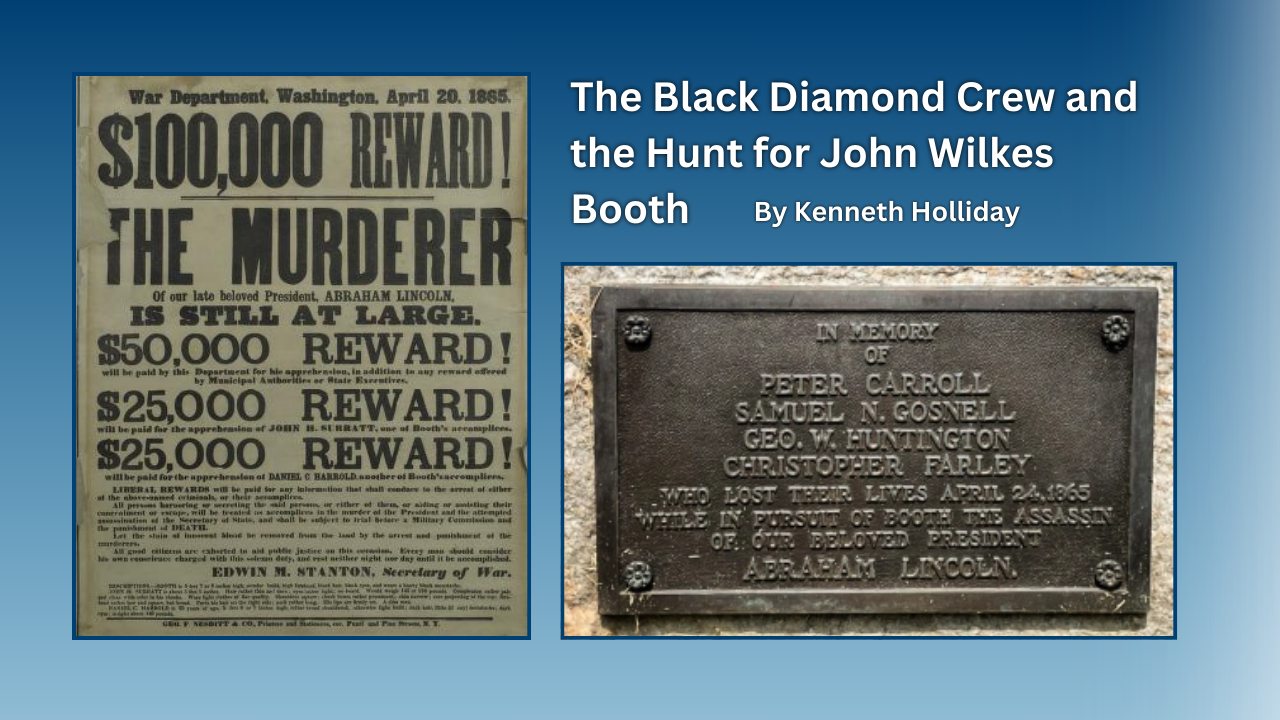

During the late evening, early hours of April 23-24, 1865, the Black Diamond, a ship on the Potomac River searching for President Abraham Lincoln's assassin John Wilkes Booth collided with another ship, the USS Massachusetts. The incident was a terrible accident during the frantic mission to locate the fleeing Booth before he escaped into Virginia. Unfortunately many lives were lost, including four civilians who had been summoned from a local fire department by the Army. For their assistance during this military operation, all four were buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery, some of the few civilians to receive that honor.

Featured Stories

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, American Expeditionary Force commander General John J. Pershing requested the recruitment of women telephone operators that were bi-lingual in English and French. Eventually 233 were selected out of over 10,000 applicants, and they served honorably through the war, earning the nickname of 'Hello Girls.'

However, their employment was not officially recognized as military service and therefore were neither honorably discharged, or eligible for the benefits other returning Veterans would receive. This kicked off a 60-year fight for 'Hello Girls' to receive legal Veteran status.

Featured Stories

Dr. Sara (Sadie) Marie Johnson Peterson Delaney was a trailblazer in promoting libraries and literacy – and worked at what would eventually become today’s VA. She was the Chief Librarian of the VA hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama, for 34 years.