A river accident leads to four civilians from Black Diamond buried in national cemetery

Many know the history of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, but few are aware of the tremendous effort it took to capture John Wilkes Booth. Fewer still know the story of the brave men who gave their life in that pursuit.

Toward the end of the Civil War, Confederate forces evacuated Richmond, Virginia. Within two weeks, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered his troops. As Washington celebrated, Booth attended a Lincoln speech on April 11, 1865. He reacted strongly to Lincoln’s suggestion that he would pursue voting rights for freed blacks. Booth allegedly told his co-conspirator David Herold, “Now, by God, I’ll put him through.” Three days later, at Ford’s Theatre, Booth made good on his threat. On Friday, April 14, 1865, Lincoln was assassinated by Booth.

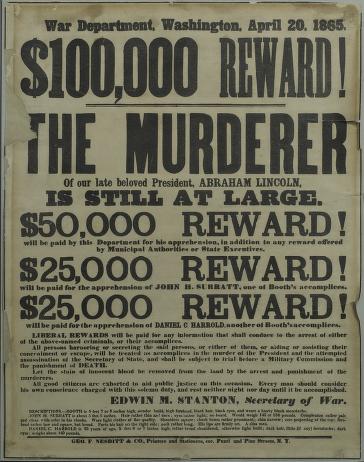

Immediately following the assassination, a massive effort was launched in search of Booth. The manhunt took place over the next few weeks. A serious concern was that Booth would cross the Potomac River back into Virginia.

Union troops were sent into southern Maryland, and ultimately to Virginia, in pursuit of Booth. Among those was a contingent from the Army Quartermaster Corps, patrolling the river in search of a boat ferrying Booth across the Potomac. Unknown to the Quartermasters, Booth and Herold had already crossed the Potomac on April 22, 1865.

This Quartermaster contingent was comprised of civilian employees from the Alexandria Fire Department. They were chartered by the U.S. Army, who had taken a military interest in the search and capture of Booth. Unfortunately, this mission would have fatal, and unforeseen, consequences.

Two ships were involved in the tragic events of April 23-24, 1865: the USS Massachusetts and the Black Diamond. The Massachusetts was heading to Norfolk, Virginia, where it was to be deployed for duty in North Carolina.

According to historical accounts, the Black Diamond was said to have had only had one light showing. Not unusual for a ship on picket duty, but it also meant it wasn’t seen in the darkness as the Massachusetts made its way downriver toward Norfolk. Around midnight, on April 23, the Massachusetts and its 400 passengers and crew collided with the Black Diamond and its crew of 20. Eighty-three men from the Massachusetts died on the river that night. As a result, many of the bodies were never recovered.

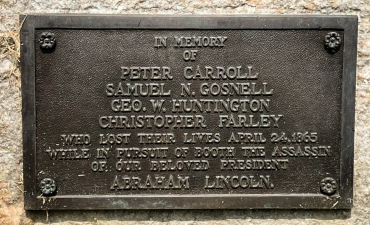

Of the 87 people who died during the collision, four were from the Black Diamond. Peter Carroll, Christopher Farley, Samuel Gosnell, and George Huntington all lost their lives in pursuit of Booth. Within 24 hours of their deaths on the Potomac, Booth was also dead.

The four Alexandrian firemen who perished in the crash were bestowed the honor of burial in the Soldier’s Cemetery in Alexandria, now known as Alexandria National Cemetery.

It is not typical for civilians to be buried in national cemeteries, which are reserved for service members, Veterans, and their families. But leaders at the time thought that’s these four individuals should receive honors for their sacrifice in pursuit of the President’s assassin.

In 1922, the federal government placed a granite boulder at the cemetery commemorating the deaths. In the 1950s the deteriorating headstones for each of the four men were replaced by new markers bearing the same design as those used for Union soldiers buried at the cemetery. Today, their headstones are some of the first markers visitors will see when entering the cemetery.

By Kenneth Holliday

Program Specialist, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

In the mid-twentieth century, the lives of Dr. Ivy Brooks and Mildred Dixon, two trailblazing Black women physicians, converged at the Tuskegee, Alabama, VA Medical Center. Doctor's Ivy Roach Brooks and Mildred Kelly Dixon shared much in common. Both women were born in 1916 in the northeastern United States and received training in East Orange, New Jersey. They both launched careers in alternate medical professions before entering the fields of radiology and podiatry, respectively. Pioneering many “firsts” throughout their professional lives, both women faced and overcame the rampant racism and sexism of the era.

Featured Stories

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, American Expeditionary Force commander General John J. Pershing requested the recruitment of women telephone operators that were bi-lingual in English and French. Eventually 233 were selected out of over 10,000 applicants, and they served honorably through the war, earning the nickname of 'Hello Girls.'

However, their employment was not officially recognized as military service and therefore were neither honorably discharged, or eligible for the benefits other returning Veterans would receive. This kicked off a 60-year fight for 'Hello Girls' to receive legal Veteran status.

Featured Stories

Dr. Sara (Sadie) Marie Johnson Peterson Delaney was a trailblazer in promoting libraries and literacy – and worked at what would eventually become today’s VA. She was the Chief Librarian of the VA hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama, for 34 years.