Telephone operators 60-year struggle for benefits after the Great War

Bells rang throughout France on the morning of Nov. 11, 1918, signifying the end of World War I. In Paris, people filled the streets in a bittersweet celebration: The war was finally over.

But while those celebrations took place, an American woman drew her last breaths in a foreign city. Inez Crittenden had been stationed in France for a year serving in the U.S. Army Signal Corps as a telephone operator. In the final days of the war, she became bed ridden with pneumonia. She died in Paris on the day the war ended.

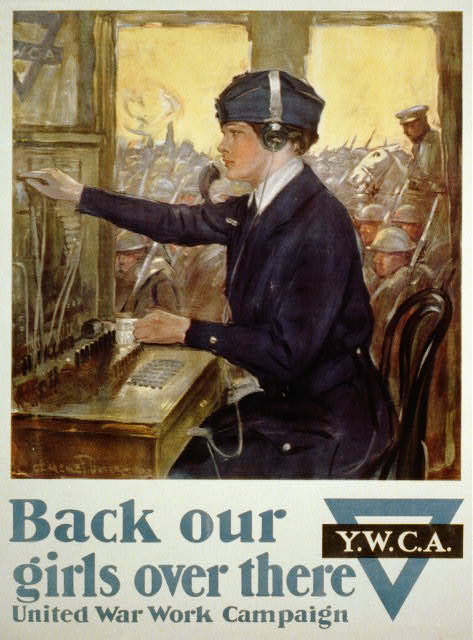

Crittenden was one of 233 women who served as telephone operators for the Army’s Signal Corps during the war. They were more commonly known as “Hello Girls.”

General Pershing’s request

After the US entered the war in 1917, the Army desperately looked for ways to improve communications during military operations. Commanders discovered major problems with the use of two languages in exchanges between the American and French armies. At first, American men and French women were used in telephone exchanges, but both groups proved to be unsatisfactory. The Army had trouble finding qualified men for the job and looked elsewhere.

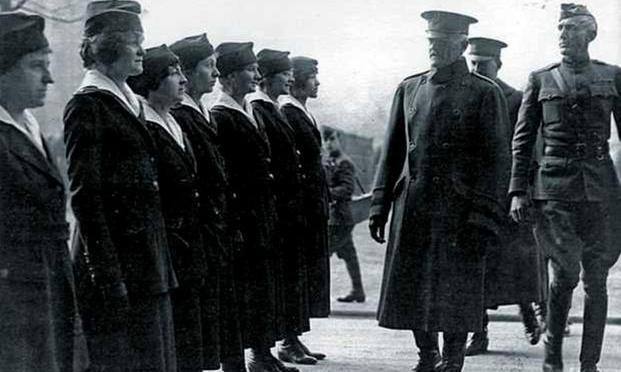

General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, requested a recruitment of women telephone operators that spoke both English and French. In America, women primarily made up the workforce of civilian telephone operators. Nearly 10,000 women applied to fill Pershing’s request. Those that were accepted into the program underwent a tough selection process and had to agree to serve for the duration of the war. The women were evaluated on tests similar to those given to Army officer candidates. Then they were individually investigated by the Secret Service. Because the nature of the work required them to handle highly confidential information, their loyalty and motivations for serving were investigated more thoroughly than the average soldier.

Military training

Their training included daily military drill. They were taught about the Army, its traditions, and military terms. They wore a uniform, were given ranks, and were subject to inspections. In every way they appeared to be soldiers. And their abilities overseas proved invaluable: They were far more effective than men in operating the military telephone and had a proficiency that was unmatched in their British counterparts. It was said that without the Hello Girls, “It would be impossible to brigade American troops.”

After she died, Inez Crittenden was given a military burial in Suresnes American Cemetery and Memorial. Her grave lies alongside over a thousand other American service members who died overseas. But after the war ended, the Army decided that the Hello Girls had served as civilians, not soldiers.

Fight for Recognition

While the Navy had opened enlistment to women during World War I, the Army did not. As a result, the Army did not consider the Hello Girls as servicewomen and did not issue honorable discharges to them. Therefore, the 233 Hello Girls were not considered to be Veterans of the war that they had served in. This began a sixty-year battle for them to be recognized for their military service.

It wasn’t until Congress passed the 1977 G.I. Improvement Bill that the Hello Girls finally received recognition from the government for their service. When President Carter signed it into law, the Hello Girls were given discharges from the military and granted Veteran benefits. Only 18 of them were still alive at the time.

Olive Shaw was one of those surviving Hello Girls. She had returned home to Massachusetts after the war and began working for Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers as her personal secretary. Shaw was one of the Hello Girls that led the sixty-year battle for Veteran status. When she died in 1980, one year after being granted Veteran benefits, she wished to be buried in the soon-to-be-opened Massachusetts National Cemetery. When the cemetery opened in October, she became the first burial there. The recognition of her military service, which had been denied to her for almost the entirety of her life, is now forever remembered at her grave.

Trailblazers

None of the other Hello Girls who died before 1977 ever had the chance to use their Veteran benefits, including being eligible to be buried in a national cemetery. The VA has since made efforts to ensure these trailblazers receive the recognition they deserve.

Marguerite Lovera died in 1959, 20 years before being granted Veteran benefits. However, it was discovered that she was interred in Golden Gate National Cemetery as an eligible spouse to Felix Lovera, an Army Veteran who had also served in World War I. Marguerite’s grave marker only read “Wife of SGT F A Lovera,” with no recognition to her own service during the war.

But in 2018, a relative of Marguerite contacted the National Cemetery Administration with information that she served as a Hello Girl. Though she wasn’t considered a Veteran when she was interred in the cemetery, she is now. Not long after NCA was notified, historians verified the information and a new grave marker was placed for Marguerite that gives proper recognition to her military service.

Even a 100 years after the war they served in ended, these women are still slowly receiving the recognition that they deserve. These trailblazers were some of the first women to serve in the Army.

Notes: This article originally appeared on VA News (formerly VAntagePoint Blog) March 2020.

By Kenneth Holliday

Program Specialist, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

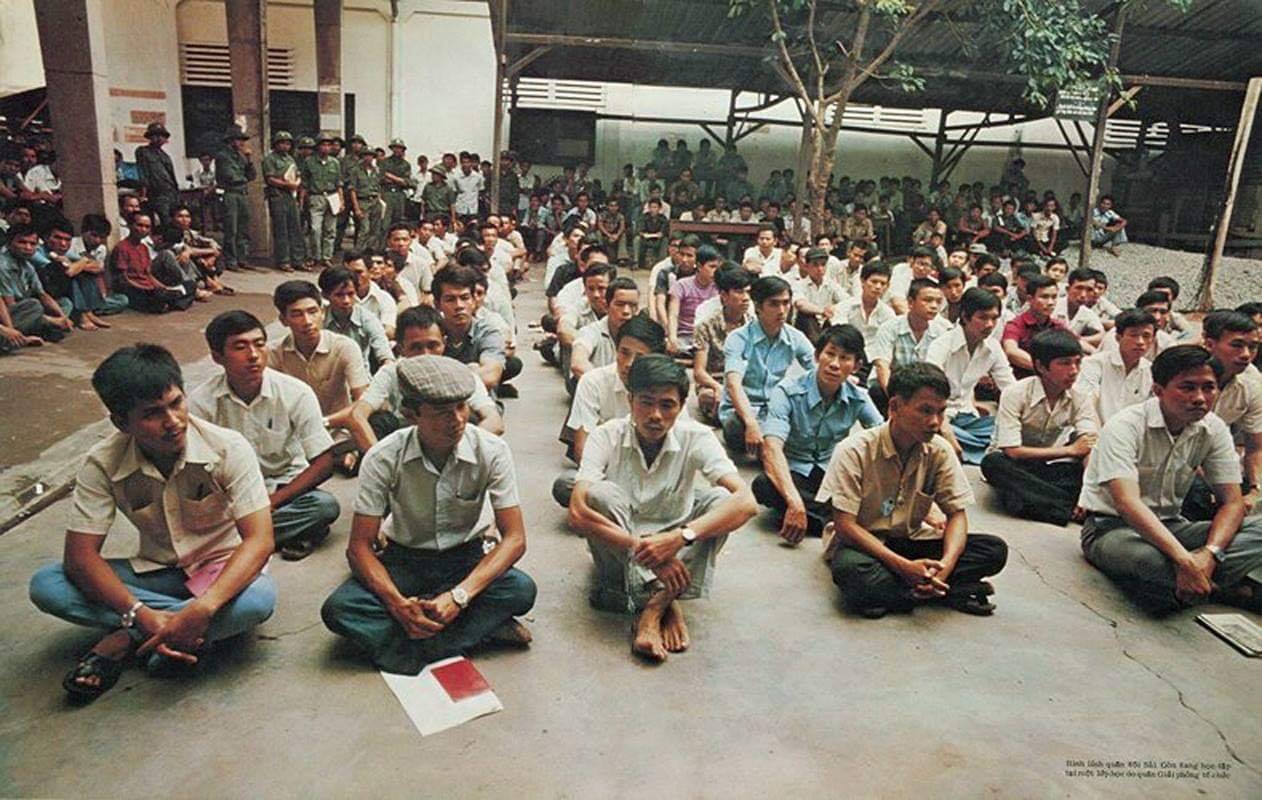

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."