Nine individuals in U.S. history have obtained the five-star general officer rank, all but one directly on account of their World War II service. Only one of this select group, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, is interred in a VA national cemetery. While all Veterans in national cemeteries are buried with equality and their gravesites treated with reverence, Nimitz’s rank generated some burial privileges not otherwise granted. His five-star insignia was included in the space normally reserved for an emblem of belief (EOB) and, at his request, the plots around him were set aside for the later burial of select colleagues. Both factors make his headstone and gravesite unique in the National Cemetery Administration’s history.

Nimitz outlived the three other WWII Navy five-star officers, all of whom accepted the entitlement of a state funeral in Washington, D.C., that came with their rank. When the administration of President John F. Kennedy approached Nimitz about planning his own services, he informed them of his desire for burial at Golden Gate National Cemetery—then administered by the U.S. Army—in a standard military funeral with a government-issued headstone. Golden Gate in the San Francisco suburb of San Bruno contains many WWII sailors and Marines, some of whom died while serving under Nimitz during his tenure as Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet. Catherine Nimitz recalled that her husband was adamant about this cemetery because “all his men from the Pacific were out here.”

At the time of his death, February 20, 1966, EOBs were a common feature on the government-issued headstone. The primary ones offered were a Latin Cross, Star of David, and the Buddhist Wheel of Righteousness. Nimitz asked that his fleet admiral insignia be used instead. His biographer speculated that, as a spiritual man who did not adhere to the beliefs of any particular denomination, Nimitz felt the five stars showed how hard he had worked in life. This is a rare instance where a symbol other than the approved EOBs was inscribed at the top of a government-issued headstone.

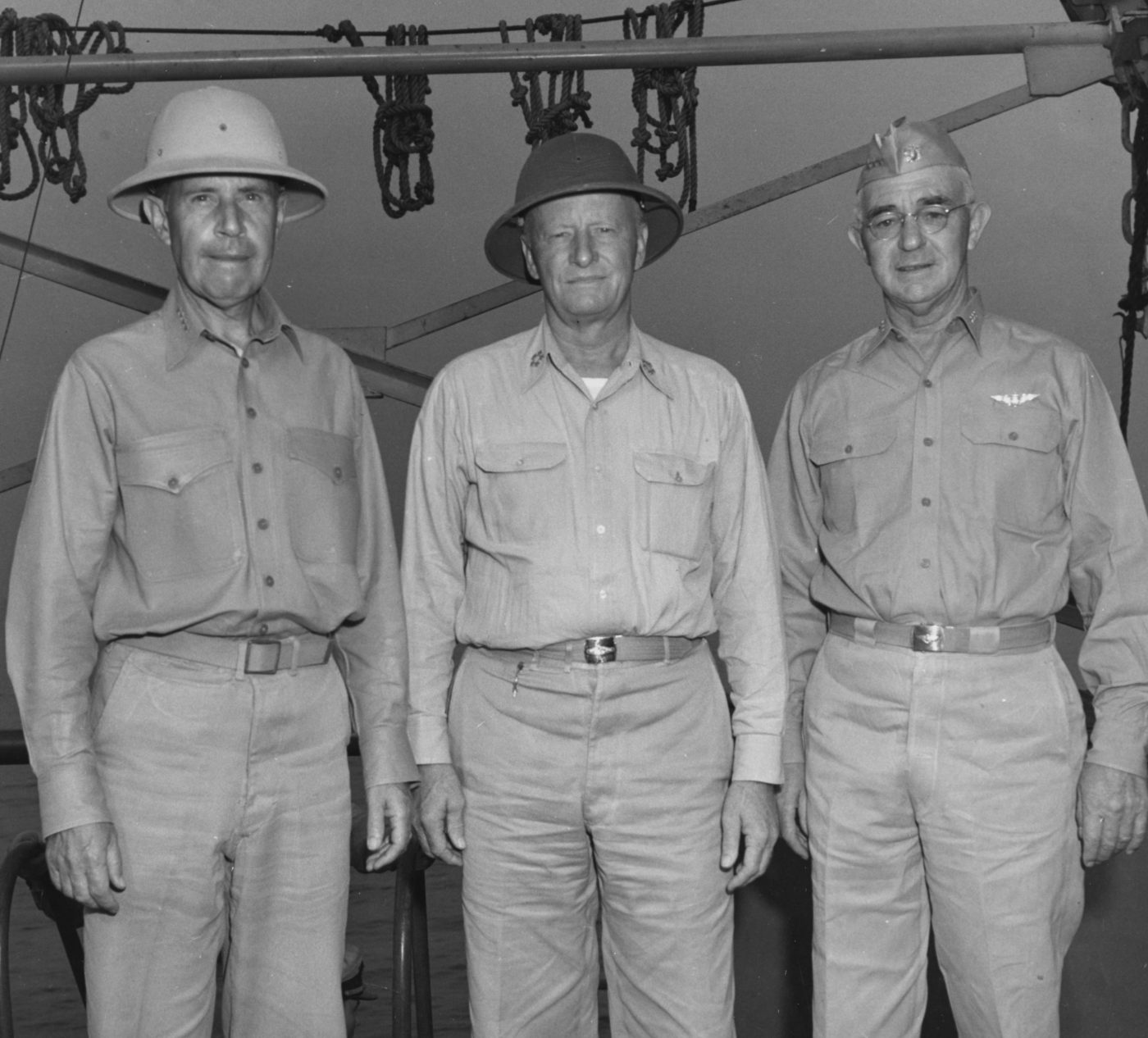

When Nimitz reserved plots for himself and his wife at Golden Gate in 1949, he personally asked to have spaces reserved right beside him for two of his most trusted subordinates and closest friends, Admirals Raymond A. Spruance and Richmond Kelley Turner. The Army denied this special request, but secretly reserved the plots without informing Nimitz until a later date.

Another close friend, Admiral Charles A. Lockwood, was later included in this arrangement. Spruance was the last of the group to die, passing away in 1969. With his burial, the “Nimitz Plot” became the final resting place of four of the Navy’s most influential leaders in the Pacific theater during World War II. The sentiment behind the burials emphasizes the symbolic power of comradeship after death in national cemeteries.

By Richard Hulver, Ph.D.

Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

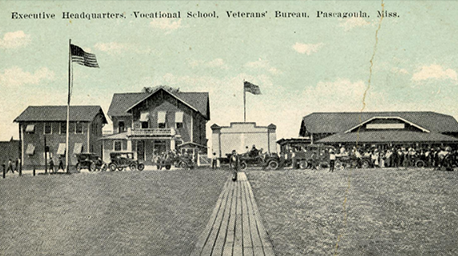

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.