Exhibits

VA Research at 100: A Century of Medical Advancements

In 1925, 100 years ago, the Veterans Bureau initiated the first hospital-based medical research studies to address Veteran-specific issues like mental health, tuberculosis, cancer and toxic exposure. The program has since made significant medical breakthroughs and innovations, impacting the world.

History of VA in 100 Objects

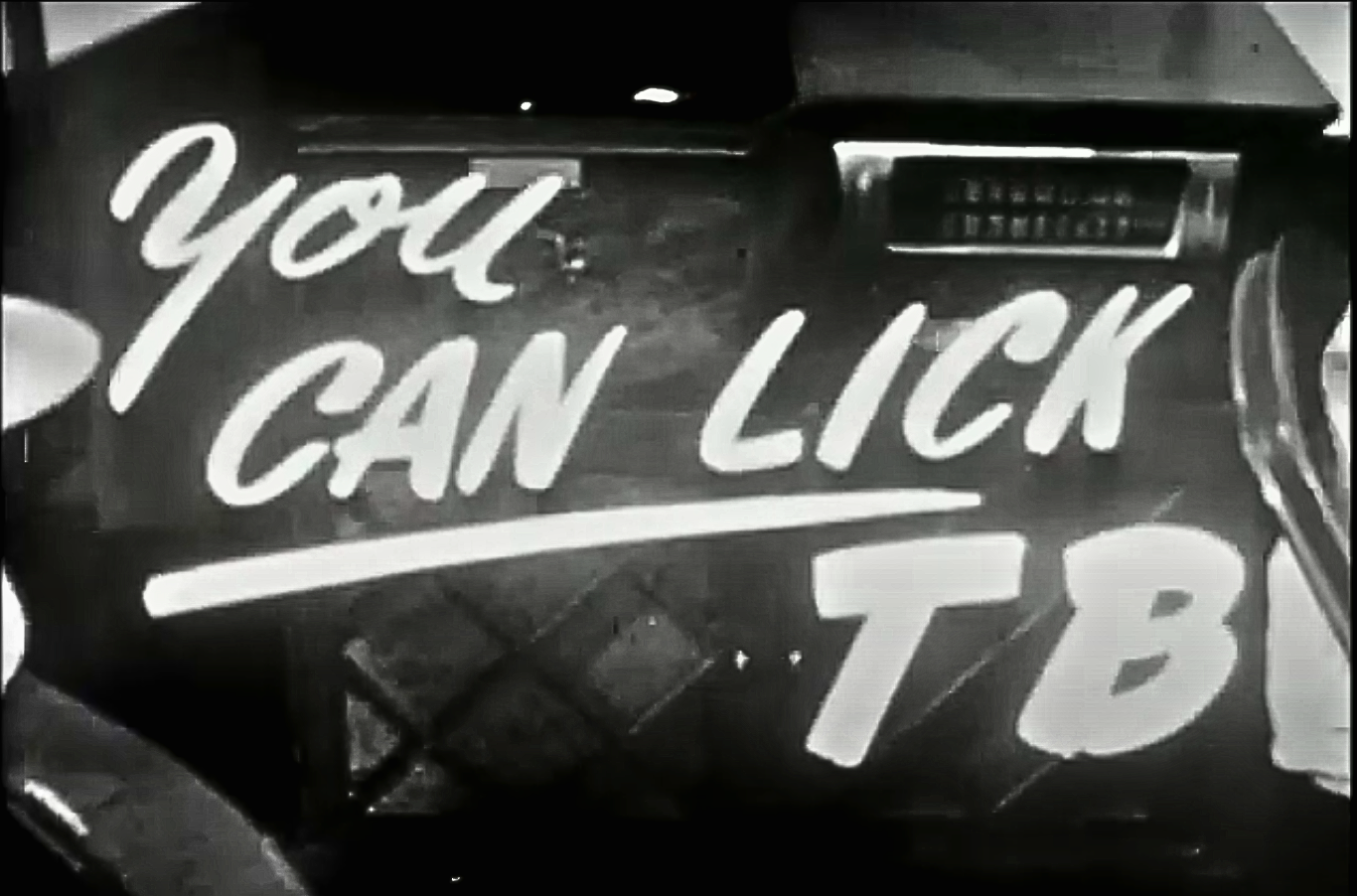

Object 89: VA Film “You Can Lick TB” (1949)

In 1949, VA produced a 19-minute film titled “You Can Lick TB.” The film follows a fictional conversation between a bedridden Veteran with tuberculosis and his VA doctor, dramatizing through brief vignettes the different stages of TB treatment and recovery.

Featured Stories

Dr. Philip Matz: A Pioneer in VA Medical Research

After World War I and the establishment of the Veterans Bureau, one of the key focuses was developing a research program.

The intent was to have the necessary statistical studies and research information to help the Bureau treat Veterans not just from World War I but all future conflicts.

The man chosen to lead this task was Dr. Philip Matz, and his work was groundbreaking in the future of Veteran healthcare.

History of VA in 100 Objects

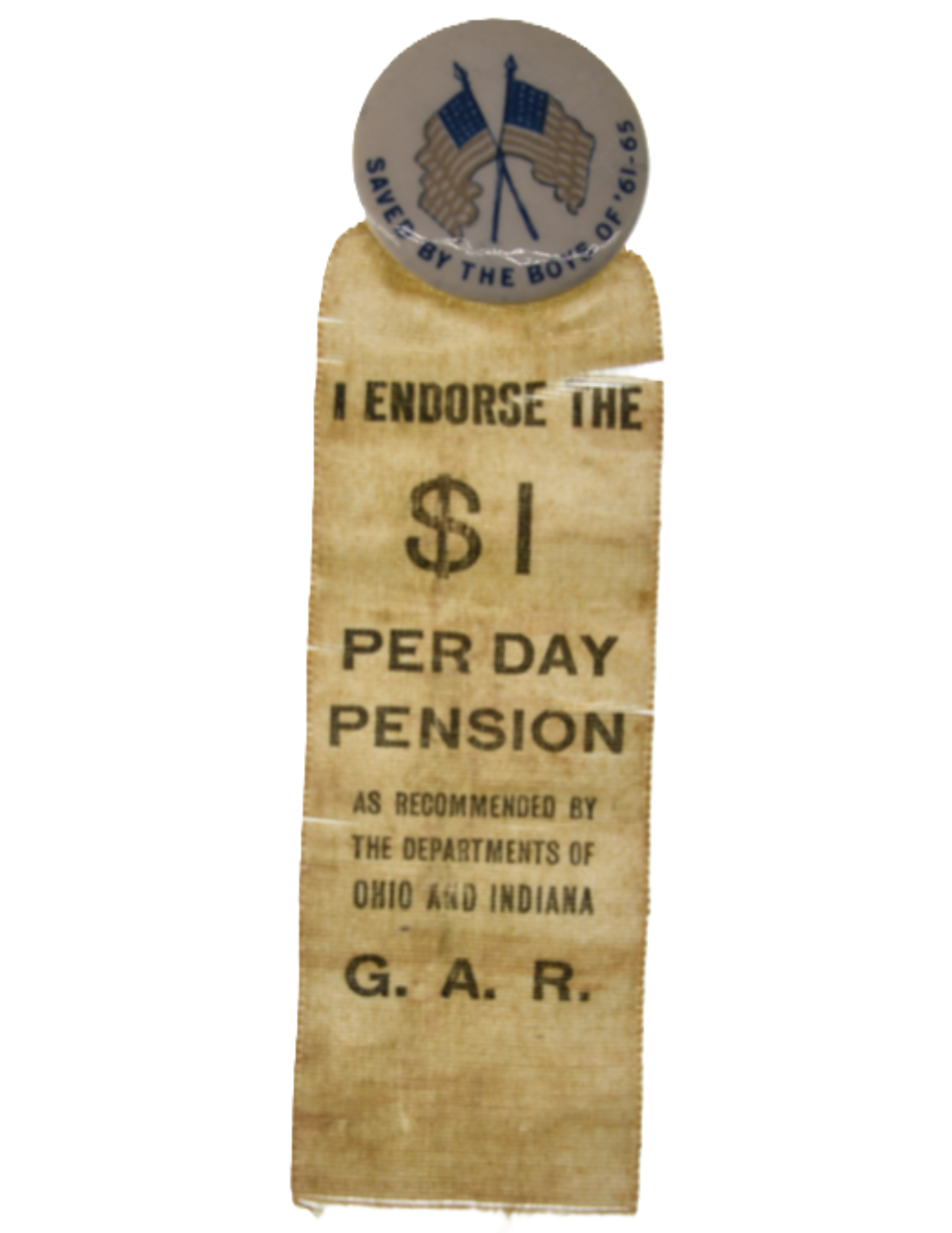

Object 85: Congressman Claypool’s “$1 Per Day Pension” Ribbon

Founded in 1866 as fraternal organization for Union Veterans, the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) embraced a new mission in the 1880s: political activism. The GAR formed a pension committee in 1881 for the express purpose of lobbying Congress for more generous pension benefits.

An artifact from the political wrangling over pensions is now part of the permanent collection of the National VA History Center in Dayton, Ohio. The item is a small pension ribbon displaying the message: “I endorse the $1 per day pension as recommended by the Departments of Ohio and Indiana G.A.R.” The button attached to the ribbon features two American flags and the phrase “saved by the boys of ’61-65.” The back of the ribbon bears the signature of Horatio C. Claypool, a Democratic judge who ran for the seat in Ohio’s eleventh Congressional district in the 1910 mid-term elections.

Featured Stories

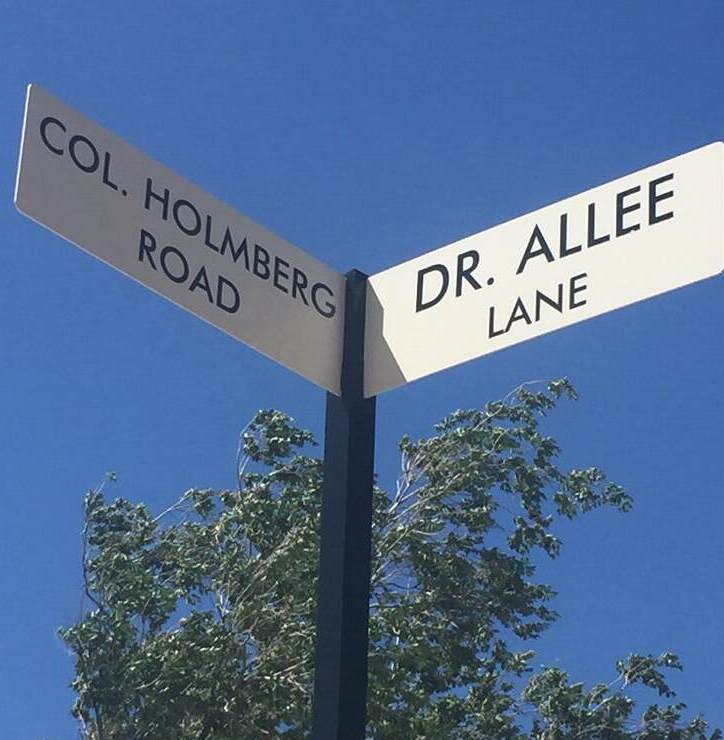

The Historic Streets of the VA Medical Center in Prescott, Arizona

Ever wonder where some historic street names come from? That's the question that pops up at the VA Medical Center in Prescott, Arizona. Multiples names are displayed on white signs, such as Holmberg, Allee and Whipple. Who are they? Dive in and find out.

Featured Stories

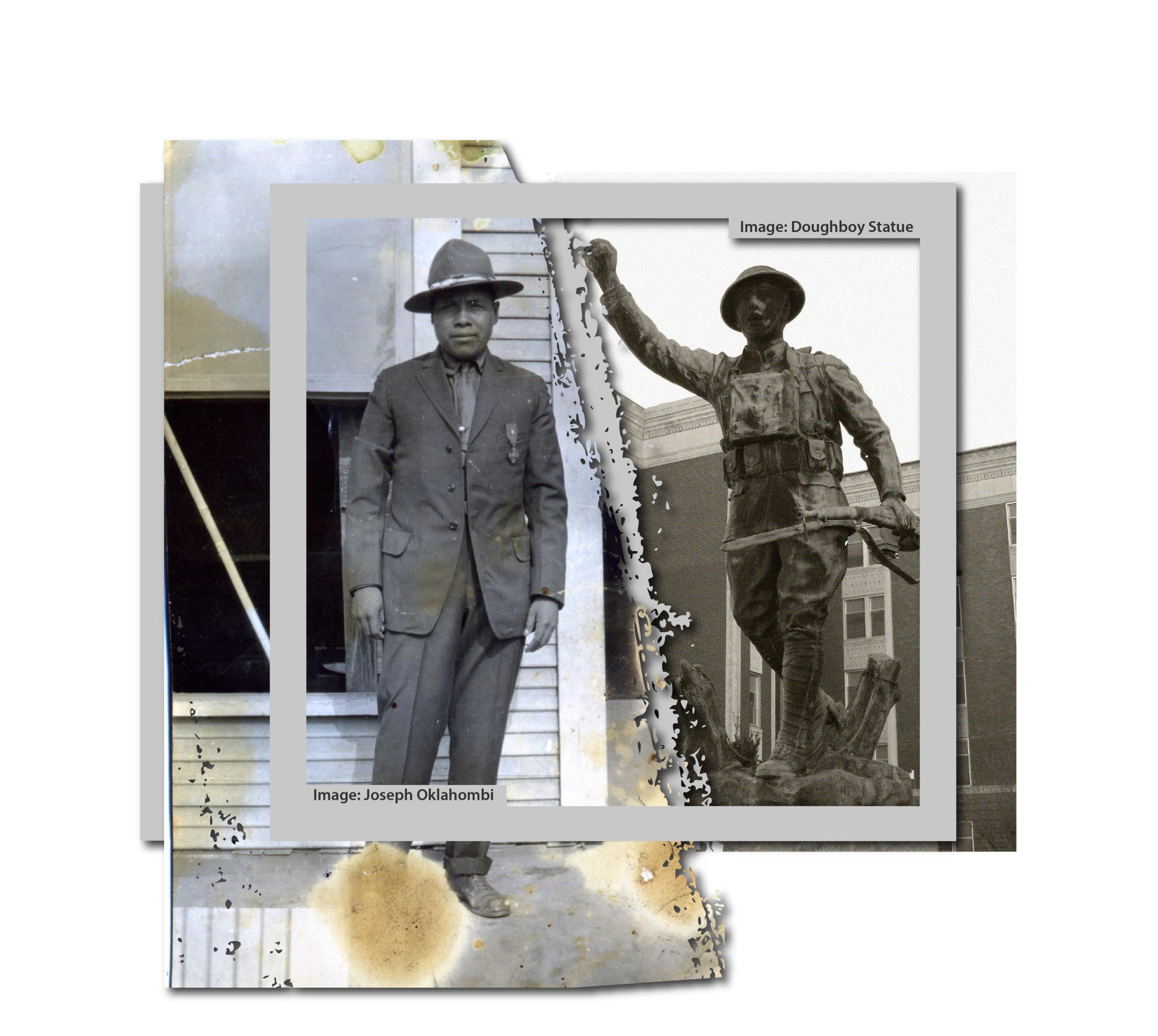

Muskogee VA: A Hundred Years of Native American Veteran Care

Native Americans have served the United States with honor, loyalty, and bravery since the Revolutionary War. Despite facing discrimination, many Native American Veterans volunteered for service throughout the centuries, making significant contributions on the battlefield. Some saw it as fighting not only to protect the United States, but also their ancestral land. For their sacrifice, the VA hospital in Muskogee has led the charge in providing exceptional care for Native American Veterans for 100 years.

History of VA in 100 Objects

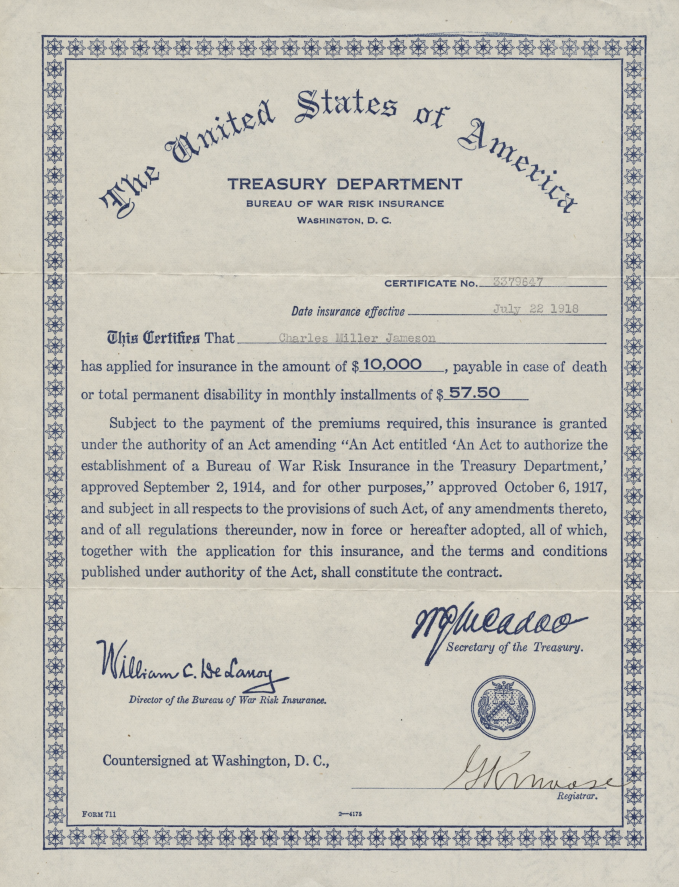

Object 81: World War I Insurance Certificate

An effort to remake the Veteran benefits system during World War I led to the 1917 War Risk Insurance Act that provided insurance benefits to Veterans well beyond their act of service was completed. A $10,000 policy could furnish the beneficiary a monthly income of over $57 in the early 20th Century.

It was a popular benefit, with 4 million applications before the end of the war. This program greatly impacted VA's future insurance efforts.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 80: LUKE/DEKA Prosthetic Arm

In the 19th century, the federal government left the manufacture and distribution of prosthetic limbs for disabled Veterans to private enterprise. The experience of fighting two world wars in the first half of the 20th century led to a reversal in this policy.

In the interwar era, first the Veterans Bureau and then the Veterans Administration assumed responsibility for providing replacement limbs and medical care to Veterans.

In recent decades, another federal agency, the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA), has joined VA as a supporter of cutting-edge research into artificial limb technology. DARPA’s efforts were spurred by the spike in traumatic injuries resulting from the emergence of improvised explosive devices as the insurgent’s weapon of choice in Iraq in 2003-04.

Out of that effort came the LUKE/DEKA prosthetic limb, named after the main character from "Star Wars."

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 78: French Cross at Cypress Hills National Cemetery in Brooklyn

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.

Curator Corner

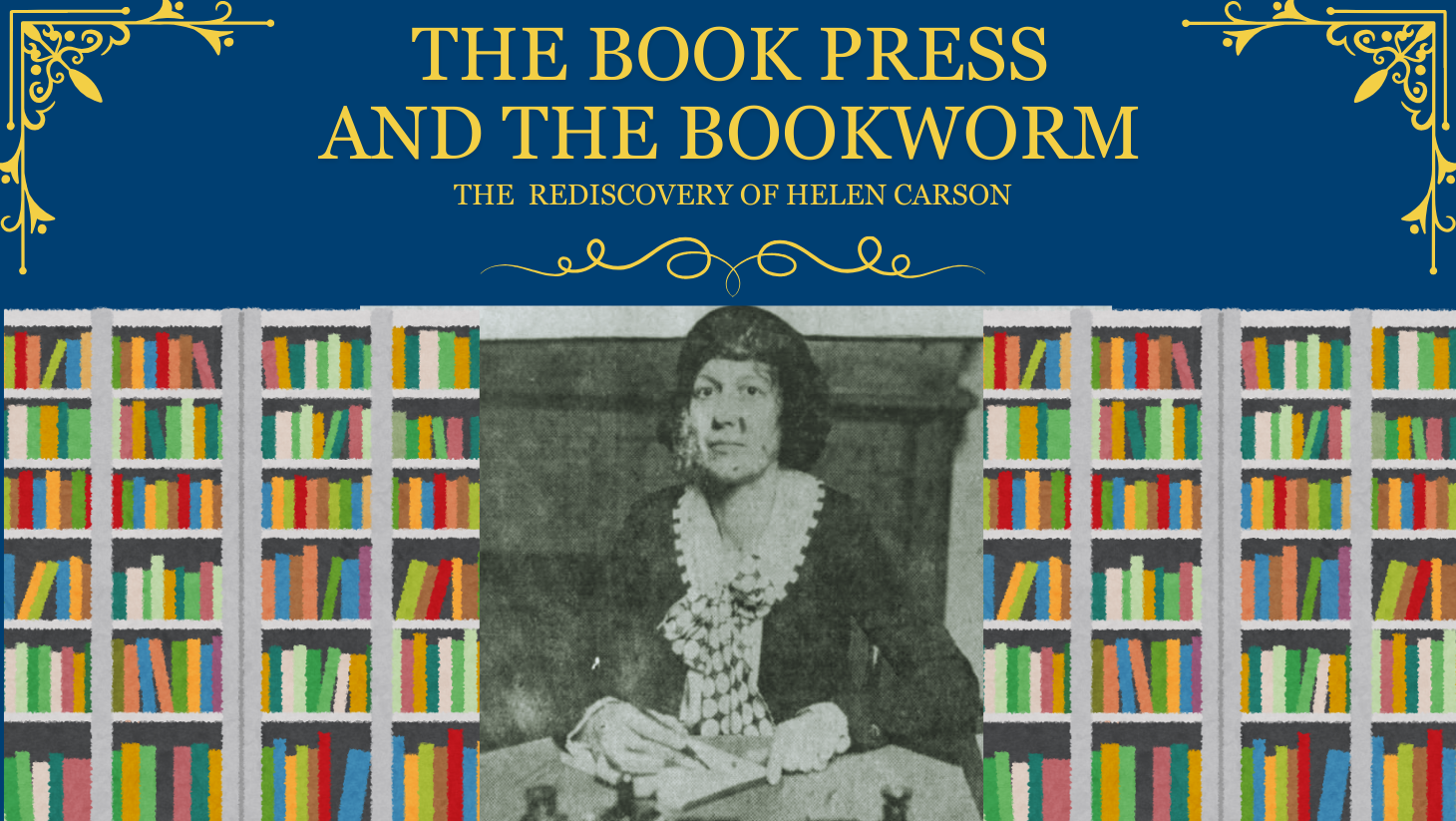

What’s in the Box? Librarian Helen Carson

It isn’t often that researchers who work with historic objects get to know the people who used those objects every day. Sometimes we get lucky and can link artifacts to certain facilities or buildings on a historic VA campus, but usually we must look for more hidden lines of evidence to figure out how an object fits into the history of those who care for our Nation’s Veterans. As nice as it would be, it isn’t as if many artifacts turn up labeled with their owners’ names! So, imagine my surprise when my teammates and I began sweeping Putnam Library for any historic objects left behind before the building is closed for renovation, and found just that.

As far as artifacts go, its story seemed simple: book presses like these would have been used to help maintain and repair the thousands of books read in Putnam Library ever since it first opened in 1879. The day that I first got up close and personal with the press, I noticed a woman’s name scraped into the black paint of the platen (the technical name for the big metal plate used to hold books together). It said “Helen Carson” in big, legible letters. As we carefully transported the heavy press down the many stairs inside Putnam Library, I looked at the name and thought “Hm…wonder who that is?”.

History of VA in 100 Objects

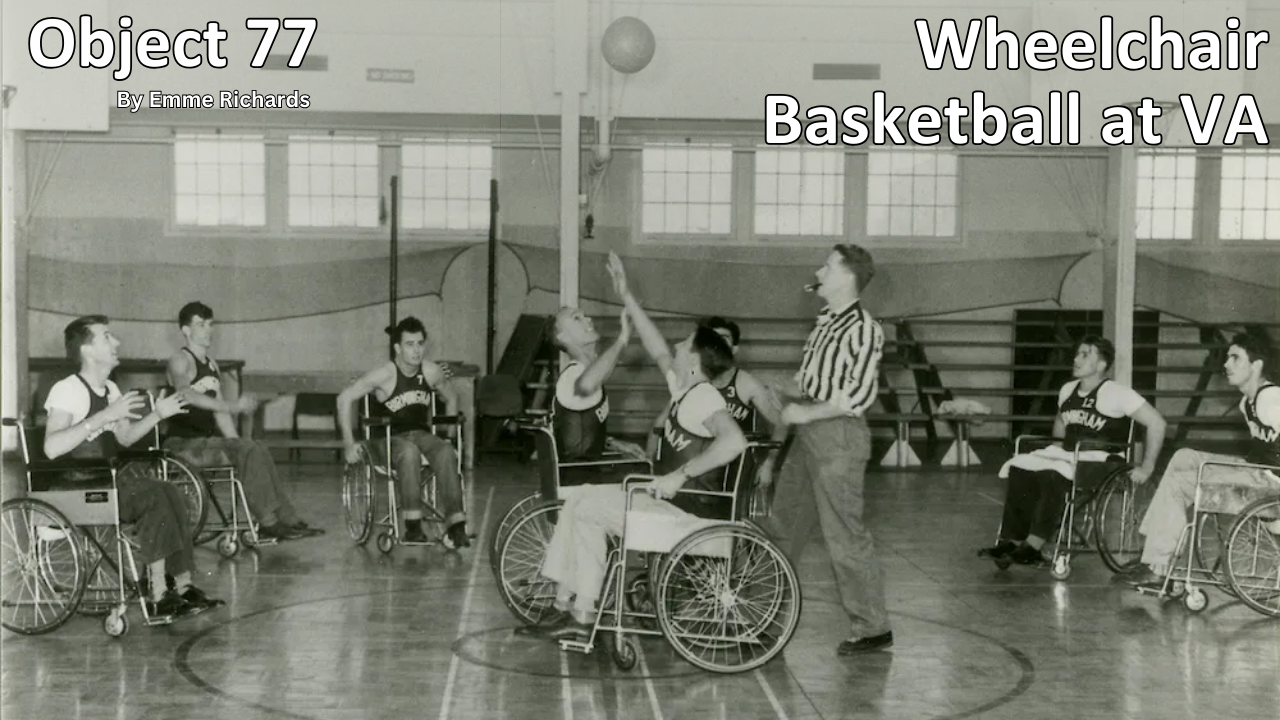

Object 77: Wheelchair Basketball at VA

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.

History of VA in 100 Objects

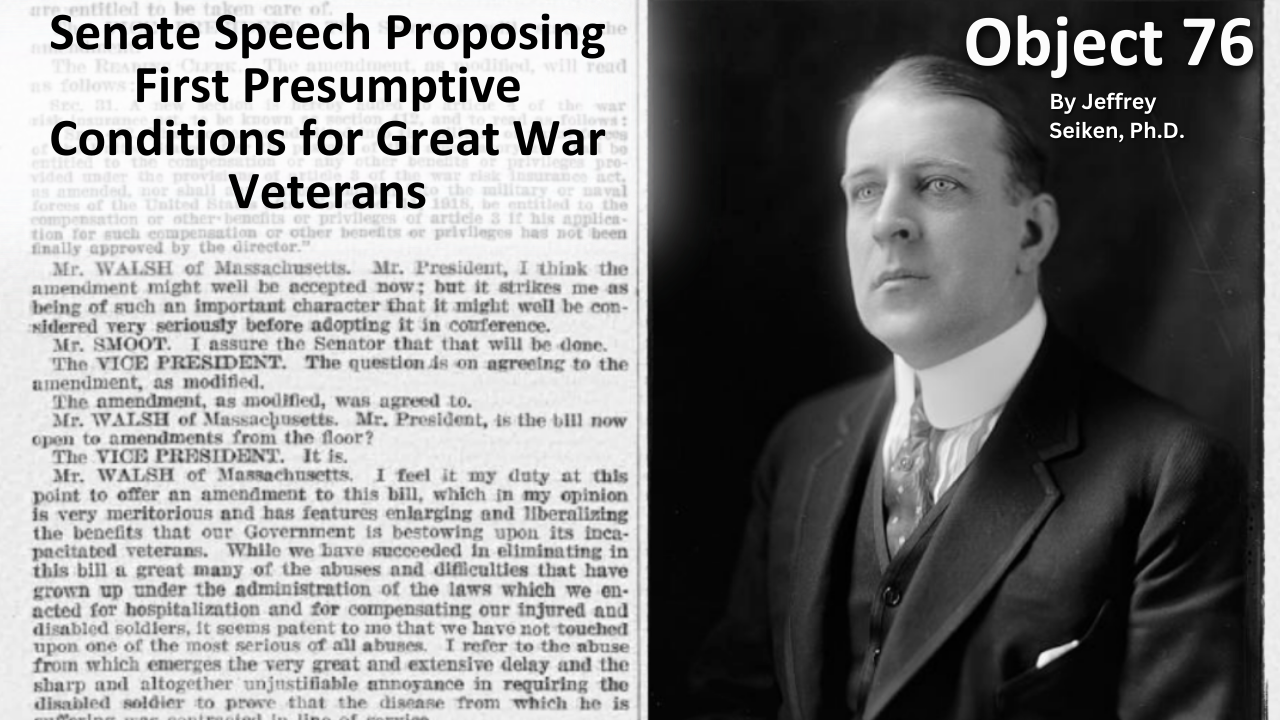

Object 76: Senate Speech Proposing First Presumptive Conditions For Great War Veterans

After World War I, claims for disability from discharged soldiers poured into the offices of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the federal agency responsible for evaluating them. By mid-1921, the bureau had awarded some amount of compensation to 337,000 Veterans. But another 258,000 had been denied benefits. Some of the men turned away were suffering from tuberculosis or neuropsychiatric disorders. These Veterans were often rebuffed not because bureau officials doubted the validity or seriousness of their ailments, but for a different reason: they could not prove their conditions were service connected.

Due to the delayed nature of the diseases, which could appear after service was completed, Massachusetts Senator David Walsh and VSOs pursued legislation to assist Veterans with their claims. Eventually this led to the first presumptive conditions for Veteran benefits.