The massive mobilization of industry and manpower resulting from the United States’ entry into World War II lifted the nation out of the Great Depression and sent the economy soaring. But even as the country enjoyed new heights of economic prosperity, American leaders worried about what would happen after the war, once industrial output and government spending returned to peacetime levels. They feared the economy might fall into another tailspin, leading to widespread unemployment and social misery, especially for the millions of Veterans reentering the labor force. Memories of World War I Veterans during the Great Depression sleeping on the streets, standing in breadlines, and marching on Washington, as 20,000 did in 1932, remained fresh in the public’s mind. This was a scenario that President Franklin D. Roosevelt, lawmakers on both sides of the political aisle, and members of the different Veterans organization wanted at all costs to avoid.

Roosevelt’s administration actually began planning for the aftermath of the war before the United States even joined the conflict. In late 1940, a full year before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt asked the small team of government and academic experts on the National Resources Planning Board to study the problem of postwar demobilization as part of a broader investigation into a range of social and economic issues. In 1942, Roosevelt formed two separate committees to focus specifically on programs to assist returning Veterans. By 1943, informed by the committees’ recommendations, Roosevelt’s own thinking on the issue had crystallized. Starting with one of his famed fireside chats in July 1943 and continuing in speeches delivered later in the year, he presented his vision of how the government should help Veterans find their footing and realize their potential following their discharge from the military. “We have taught our youth how to wage war; we must also teach them how to live useful and happy lives in freedom, justice, and decency,” he informed Congress. To this end, he called on lawmakers to provide Veterans with mustering-out pay, unemployment insurance, quality medical and hospital care, and support for higher education and job training.

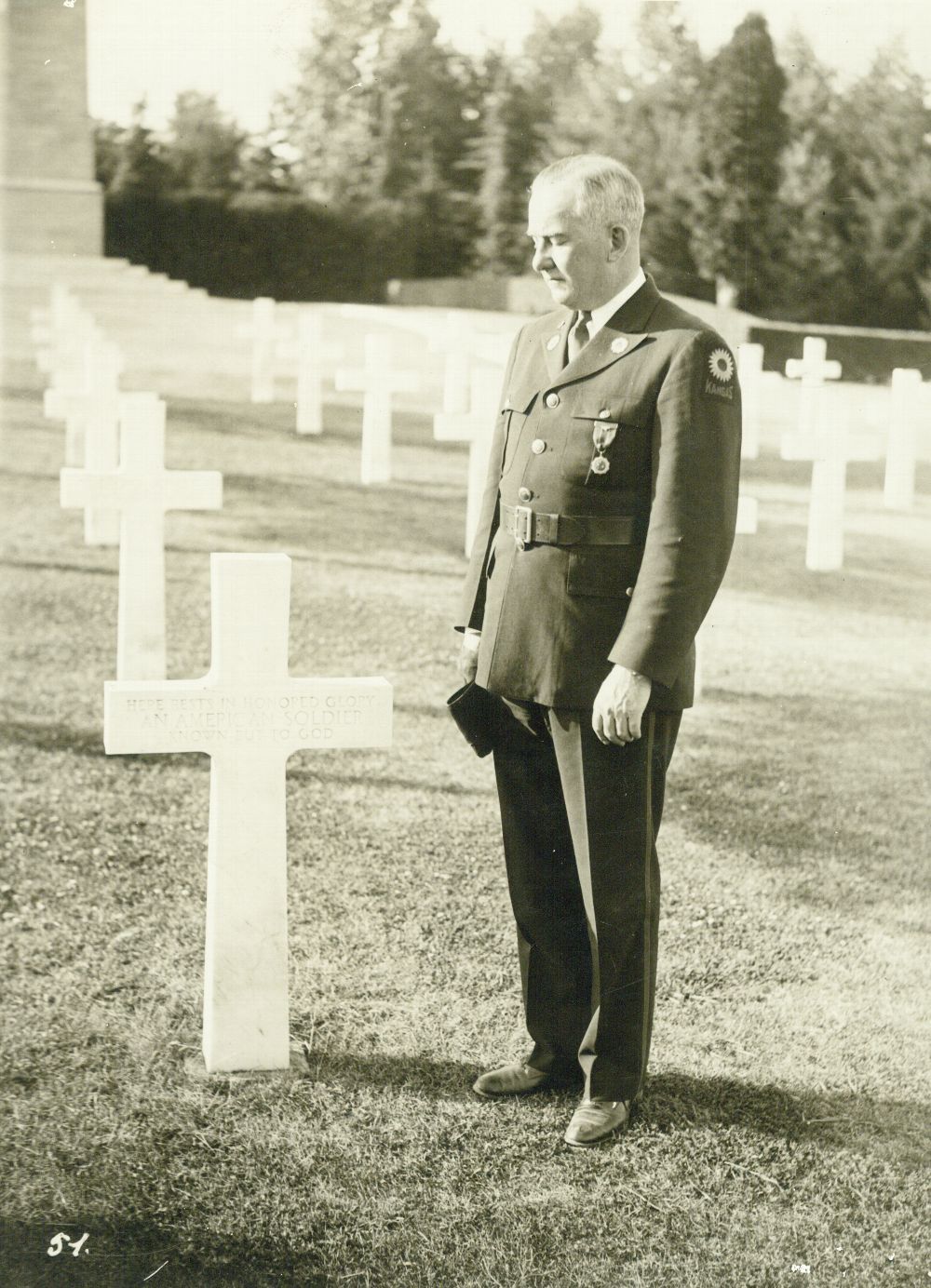

By the end of 1943, numerous bills containing parts and pieces of the president’s plan were circulating in Congress. It was at this juncture that the American Legion entered the legislative fray. Founded in 1919, the Legion had established itself as the largest and most influential Veterans organization in the nation, with more than a million members nationwide and overseas. In late November 1943, the national commander of the Legion, Warren H. Atherton, assembled a committee composed of some of the organization’s most distinguished members to prepare a bill for Congress. John H. Stelle, a staunch Roosevelt supporter who had served briefly as governor of Illinois, chaired the panel. Harry W. Colmery, a World War I Veteran, prominent lawyer, and former Legion national commander, also joined after receiving a letter from Atherton asking him “to serve on a committee which will have the most important job of this year.”

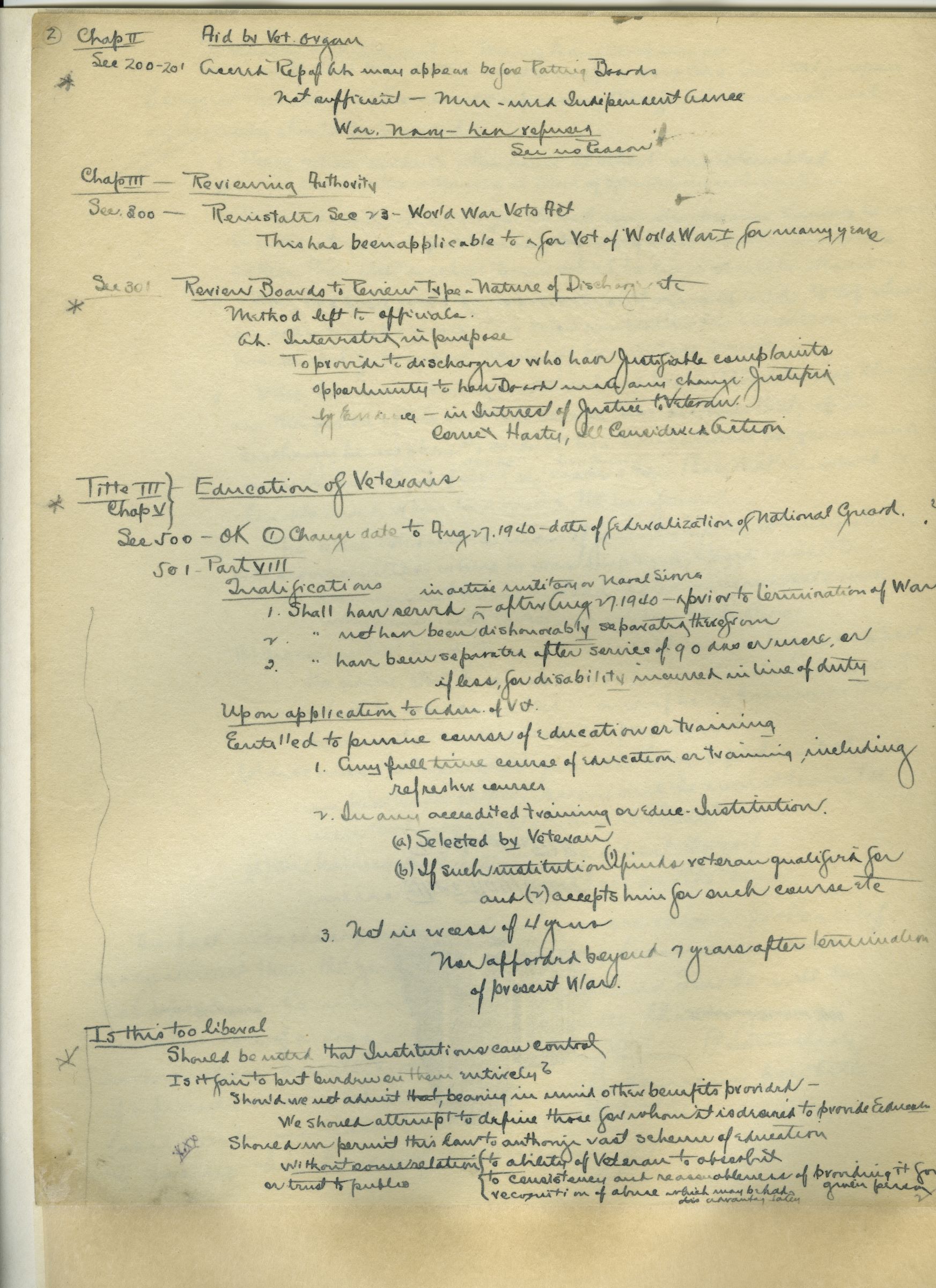

Stelle, Colmery, and the other committee members gathered in Washington, D.C., in mid-December and went to work. Over a frenzied three weeks, they collected information and interviewed government and private sector authorities in banking, education, employment, and other fields. They also debated among themselves what should go into the bill and how it should be structured. Colmery took on the task of translating the mass of data and the group’s internal deliberations into concrete legislative language. Chairman Stelle would later credit Colmery with “[jelling] all of our ideas into words.” He holed up in the Mayflower Hotel during the long winter evenings, sometimes working through the night. He wrote out a rough sketch of the bill in long hand on the hotel’s stationary. After revising the initial draft, the committee on January 8, 1944, felt ready to present its work to Congress, the president, and the public. In an inspired bit of branding, the Legion’s acting director of public relations, Jack Cejnar, came up with memorable name for the bill. He dubbed it “the G.I. Bill of Rights.”

The Legion bill incorporated the main elements of Roosevelt’s proposals—most notably, unemployment compensation and educational assistance— while adding several important new provisions, all rolled up into a single piece of legislation. The most significant of these new measures was a mechanism for the government to guarantee loans to help Veterans purchase a house, farm, or business. The bill also stipulated that all benefits were to be managed by the Veterans Administration to ensure that Veterans did not have to contend with multiple government agencies as had been the case after World War I. The bill was introduced in Congress on January 10 and 11. A few days later, Atherton and Stelle met with Roosevelt for 45 minutes at the White House to brief the president on the bill’s features.

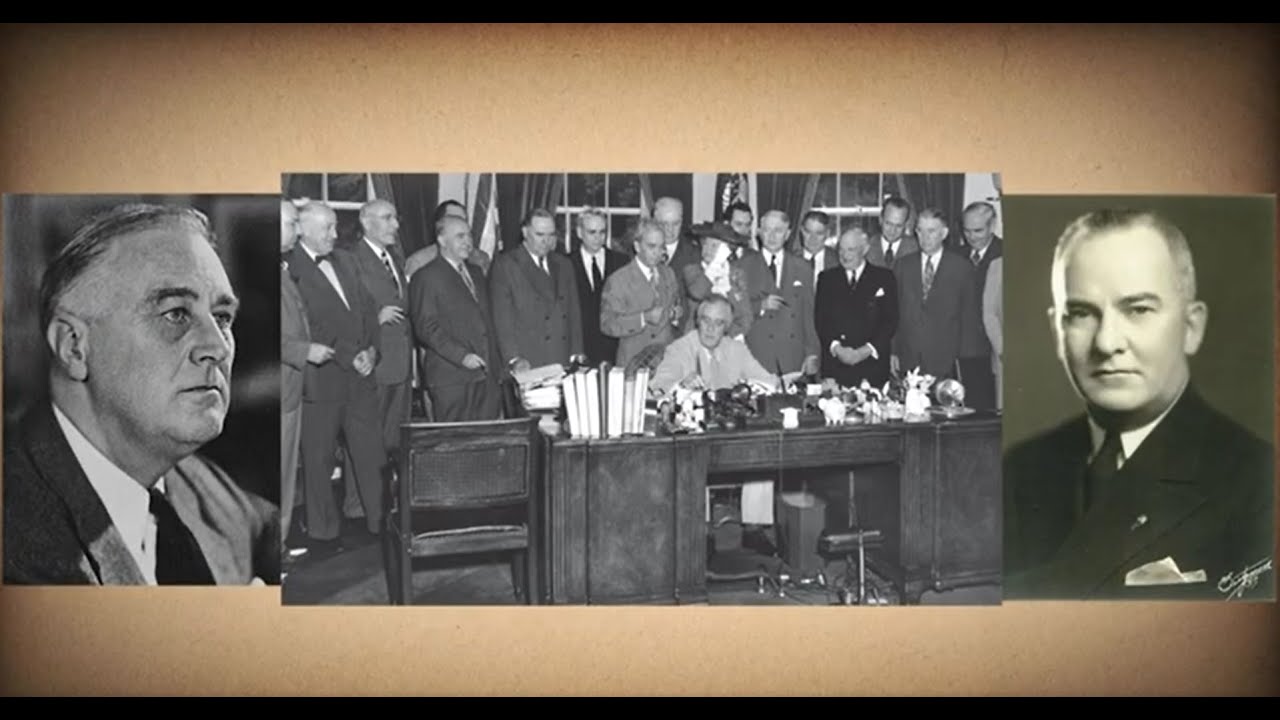

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, as the G.I. Bill was officially designated, underwent many changes as it made its way through the House and Senate but the finished product was still recognizably the Legion’s handiwork. Fittingly, the organization was well represented when President Roosevelt signed the bill on June 22, 1944. Stelle and Colmery were among the Legionnaires in attendance at the invitation of the White House. In a statement released the same day, Roosevelt celebrated the significance of what it meant for the G.I. Bill to become law: “With the signing of this bill a well-rounded program of special veterans’ benefits is nearly completed. It gives emphatic notice to the men and women in our armed forces that the American people do not intend to let them down.”

The latest episode of VA History in Focus: 100 Objects recounts the behind-the-scenes planning and legislative maneuvers that led to the passage of the historic 1944 GI Bill. In one of his famed fireside chats, President Franklin Roosevelt promised servicemembers “that the American people would not let them down when the war is won.” The American Legion helped him deliver on that promise, presenting Congress with a draft bill dubbed “the GI Bill of Rights.” The GI Bill proved to be one of the most transformative pieces of social legislation in U.S. history, enabling millions of returning Veterans to buy a home or advance their education. It also set a new standard for Veterans benefits that remains in place today.

The latest episode of VA History in Focus: 100 Objects recounts the behind-the-scenes planning and legislative maneuvers that led to the passage of the historic 1944 GI Bill. In one of his famed fireside chats, President Franklin Roosevelt promised servicemembers “that the American people would not let them down when the war is won.” The American Legion helped him deliver on that promise, presenting Congress with a draft bill dubbed “the GI Bill of Rights.” The GI Bill proved to be one of the most transformative pieces of social legislation in U.S. history, enabling millions of returning Veterans to buy a home or advance their education. It also set a new standard for Veterans benefits that remains in place today. By Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D.

Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the 19th century, the federal government left the manufacture and distribution of prosthetic limbs for disabled Veterans to private enterprise. The experience of fighting two world wars in the first half of the 20th century led to a reversal in this policy.

In the interwar era, first the Veterans Bureau and then the Veterans Administration assumed responsibility for providing replacement limbs and medical care to Veterans.

In recent decades, another federal agency, the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA), has joined VA as a supporter of cutting-edge research into artificial limb technology. DARPA’s efforts were spurred by the spike in traumatic injuries resulting from the emergence of improvised explosive devices as the insurgent’s weapon of choice in Iraq in 2003-04.

Out of that effort came the LUKE/DEKA prosthetic limb, named after the main character from "Star Wars."

History of VA in 100 Objects

American prisoners of war from World War II, Korea, and Vietnam faced starvation, torture, forced labor, and other abuses at the hands of their captors. For those that returned home, their experiences in captivity often had long-lasting impacts on their physical and mental health. Over the decades, the U.S. government sought to address their specific needs through legislation conferring special benefits on former prisoners of war.

In 1978, five years after the United States withdrew the last of its combat troops from South Vietnam, Congress mandated VA carry out a thorough study of the disability and medical needs of former prisoners of war. In consultation with the Secretary of Defense, VA completed the study in 14 months and published its findings in early 1980. Like previous investigations in the 1950s, the study confirmed that former prisoners of war had higher rates of service-connected disabilities.

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.