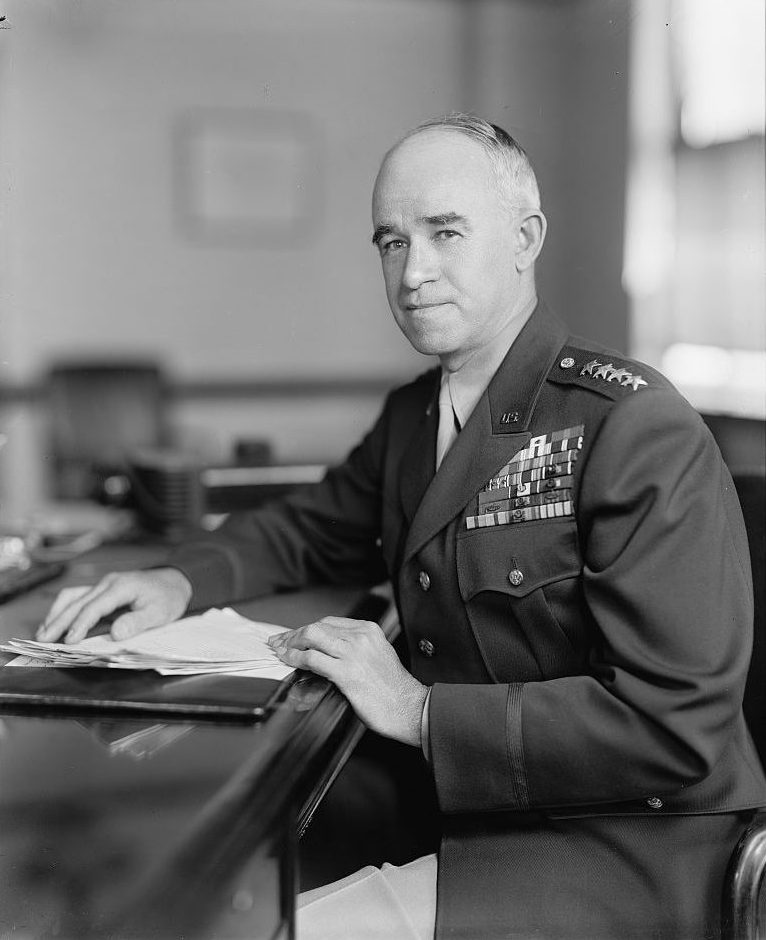

Within days of Germany’s surrender in May 1945, General Omar N. Bradley received word of his next assignment: he had been handpicked by President Harry S. Truman to replace Frank T. Hines as the next head of the Veterans Administration. For Bradley, who had commanded the 12th Army Group, the largest American fighting force ever assembled, in the campaign that liberated France and brought Germany to its knees, the president’s summons came as a shock. As he recalled in his autobiography, “I knew absolutely nothing about the Veterans Administration.”1

Truman, however, was certain he had the right man for the job. During the war, Bradley had acquired a reputation as the soldier’s general for his unassuming manner and devotion to the welfare of the troops. He had also earned the admiration of the public and Congress for his sterling record on the battlefield. As the war wound down, critics had assailed the VA for the quality of its medical care and its rigid bureaucracy. The VA needed a thorough overhaul and Truman believed Bradley possessed the judgment to make the necessary changes as well as the stature to restore trust and confidence in the embattled agency.

Bradley took the oath of office as Administrator of the VA on August 15, 1945, one day after Japan surrendered, ending World War II. A private law passed by Congress the previous month allowed him to remain on active duty and retain his four-star rank in the Army for the duration of his term. The magnitude of the task ahead of him was immense.

At the time of his appointment, the VA was already struggling to keep up with the demand for benefits and services from the 4.5 million Veterans on its rolls. Its predicament only grew worse when the Pentagon, responding to pressure from the public and politicians, sped up the pace of demobilization after the war.2 Between October 1945 and June 1946, nearly 13 million men and women in uniform returned to civilian life. Mail poured into the VA’s offices at a rate as high as 300,000 letters per day, swamping the agency with requests from Veterans seeking to use the education and loan provisions of the 1944 GI Bill or collect on the other benefits they were due.

Bradley moved swiftly after his swearing in to bring order to the chaos. He entrusted the transformation of the VA’s medical services to Major General Paul R. Hawley, who served as the Army’s chief surgeon in the European Theater of Operations during the war.3 He also brought in many of his trusted subordinates from the 12th Army Group to fill key administrative posts. To decentralize operations, Bradley launched a sweeping reorganization of the VA. He established 13 branch offices, each of which functioned, in his words, as “a small-scale VA.”4 Every branch had its own deputy administrator, who was responsible for making decisions and overseeing the smaller regional and contact offices that fell within his geographic area.

Bradley also went on a hiring spree, increasing the number of employees working throughout the VA from 65,000 in 1945 to 200,000 in 1947. He took advantage of the Veterans’ Preference Act passed in 1944 to ensure that the vast majority of the new hires were former service members themselves.

Bradley stayed at the VA for a little over two years. He stepped down from his post in November 1947 to assume the one desk job in Washington he truly coveted—Chief of Staff of the Army. He departed knowing that the VA had weathered the worst of the demobilization storm and delivered on the nation’s promises to the men and women who served bravely during World War II. By the end of his tenure, the VA had processed disability claims from over 3.5 million Veterans and helped millions more purchase homes, attend college, or enroll in job training programs through the GI Bill.

Footnotes

- Omar N. Bradley and Clay Blair, A General’s Life: An Autobiography by General of the Army Omar N. Bradley (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983), p. 440. ↩︎

- For more on the military’s efforts to bring home the millions of soldiers serving overseas, see VA Insider, “Looking back at the end of a global war.” ↩︎

- For the reforms to the VA’s medical system carried out by General Hawley, see VA Insider, “Armistice Day 1945: How VA met the moment on Veteran health care 75 years ago. ↩︎

- Bradley and Blair, A General’s Life, p. 450. ↩︎

By Jeffrey Seiken

Ph.D., Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

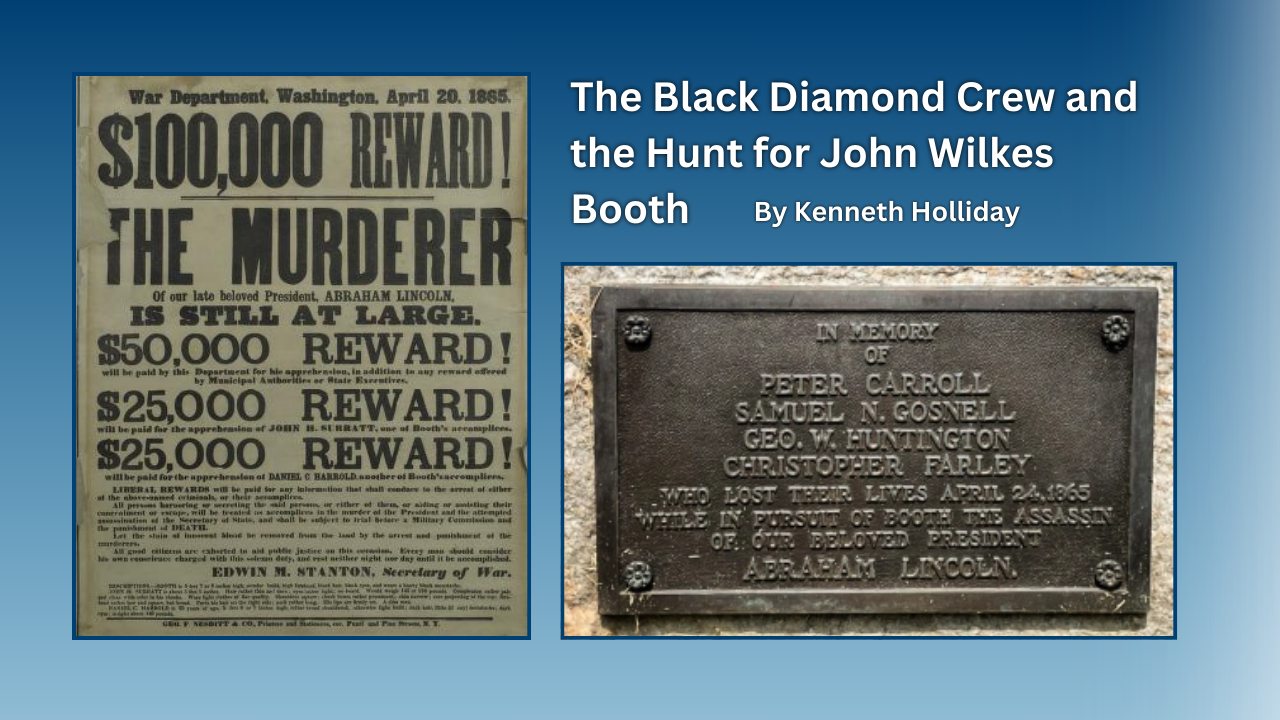

During the late evening, early hours of April 23-24, 1865, the Black Diamond, a ship on the Potomac River searching for President Abraham Lincoln's assassin John Wilkes Booth collided with another ship, the USS Massachusetts. The incident was a terrible accident during the frantic mission to locate the fleeing Booth before he escaped into Virginia. Unfortunately many lives were lost, including four civilians who had been summoned from a local fire department by the Army. For their assistance during this military operation, all four were buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery, some of the few civilians to receive that honor.

Featured Stories

In the mid-twentieth century, the lives of Dr. Ivy Brooks and Mildred Dixon, two trailblazing Black women physicians, converged at the Tuskegee, Alabama, VA Medical Center. Doctor's Ivy Roach Brooks and Mildred Kelly Dixon shared much in common. Both women were born in 1916 in the northeastern United States and received training in East Orange, New Jersey. They both launched careers in alternate medical professions before entering the fields of radiology and podiatry, respectively. Pioneering many “firsts” throughout their professional lives, both women faced and overcame the rampant racism and sexism of the era.

Featured Stories

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, American Expeditionary Force commander General John J. Pershing requested the recruitment of women telephone operators that were bi-lingual in English and French. Eventually 233 were selected out of over 10,000 applicants, and they served honorably through the war, earning the nickname of 'Hello Girls.'

However, their employment was not officially recognized as military service and therefore were neither honorably discharged, or eligible for the benefits other returning Veterans would receive. This kicked off a 60-year fight for 'Hello Girls' to receive legal Veteran status.