The North’s victory in the Civil War came at an enormous cost to the more than two million men who fought for the Union cause. Over 350,000 lost their lives due to battle or disease. Almost as many were wounded in action. Some escaped with minor flesh wounds but others suffered more lasting injuries that left their bodies scarred, damaged, or worse. According to Northern medical records, Union surgeons performed just under 30,000 amputations during the war, although the actual number was almost certainly higher. Roughly 75 percent of the patients survived these operations and returned to civilian life missing one or more limbs or other body parts.

Congress made provisions to provide monetary compensation to the wounded or disabled at the beginning of the war. In July 1861, lawmakers hastily passed a law for recruits who answered President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion, making them eligible for the same pension allowances as soldiers in the Regular Army. A year later, after it became apparent that there would be no speedy end to the conflict, Congress enacted a more comprehensive pension act called the General Law. It was modeled on the pension legislation passed for Veterans of the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and Mexican War, although it was more liberal in one important respect. For the first time, a pension law explicitly granted benefits not just to men wounded in battle but also to those suffering from “disease contracted while in the service of the United States.” This stipulation vastly increased the pool of eligible claimants, as sickness and disease ran rampant in the ranks during the war. Over the next 36 years, almost 60 percent of the more than 400,000 pensions awarded to Civil War Veterans would be for non-battlefield causes.

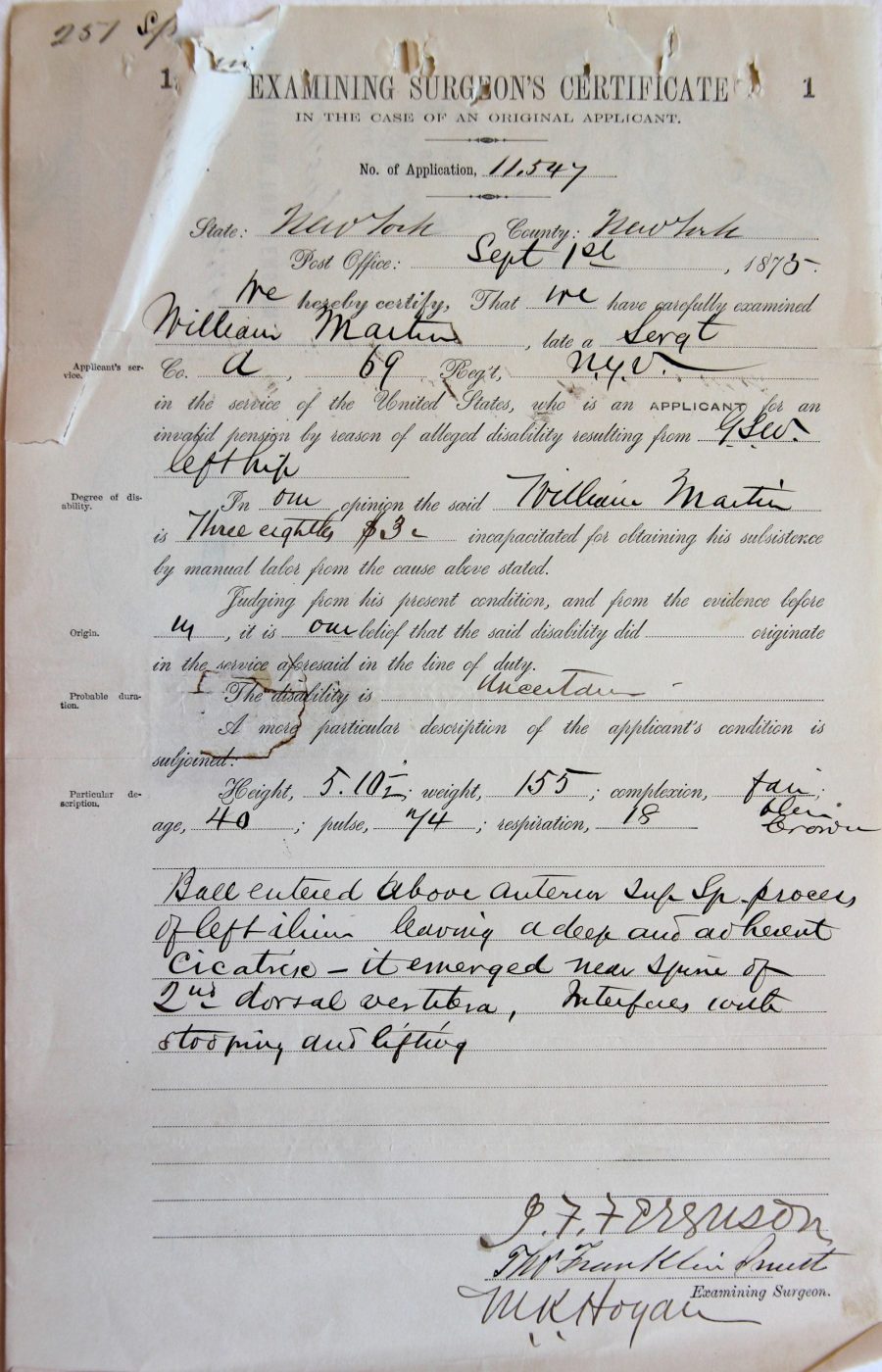

In other respects, the 1862 act followed the practices of previous pension laws. As had been the case since the American Revolution, payment rates depended on rank (at the time of injury) and the severity of the disability. If fully disabled, privates and non-commissioned officers received $8 a month, an amount fixed by law back in 1816. At the other end of the payment spectrum, officers at the rank of lieutenant colonel or higher received $30. Proportionally smaller sums were awarded for injuries that were determined to be less than completely debilitating by examining physicians. In evaluating a Veteran’s condition, medical officials used the criteria that had been in place since 1806: they assessed the “nature of such disability, and in what degree it prevents the claimant from obtaining his subsistence”—meaning a living—by manual labor.

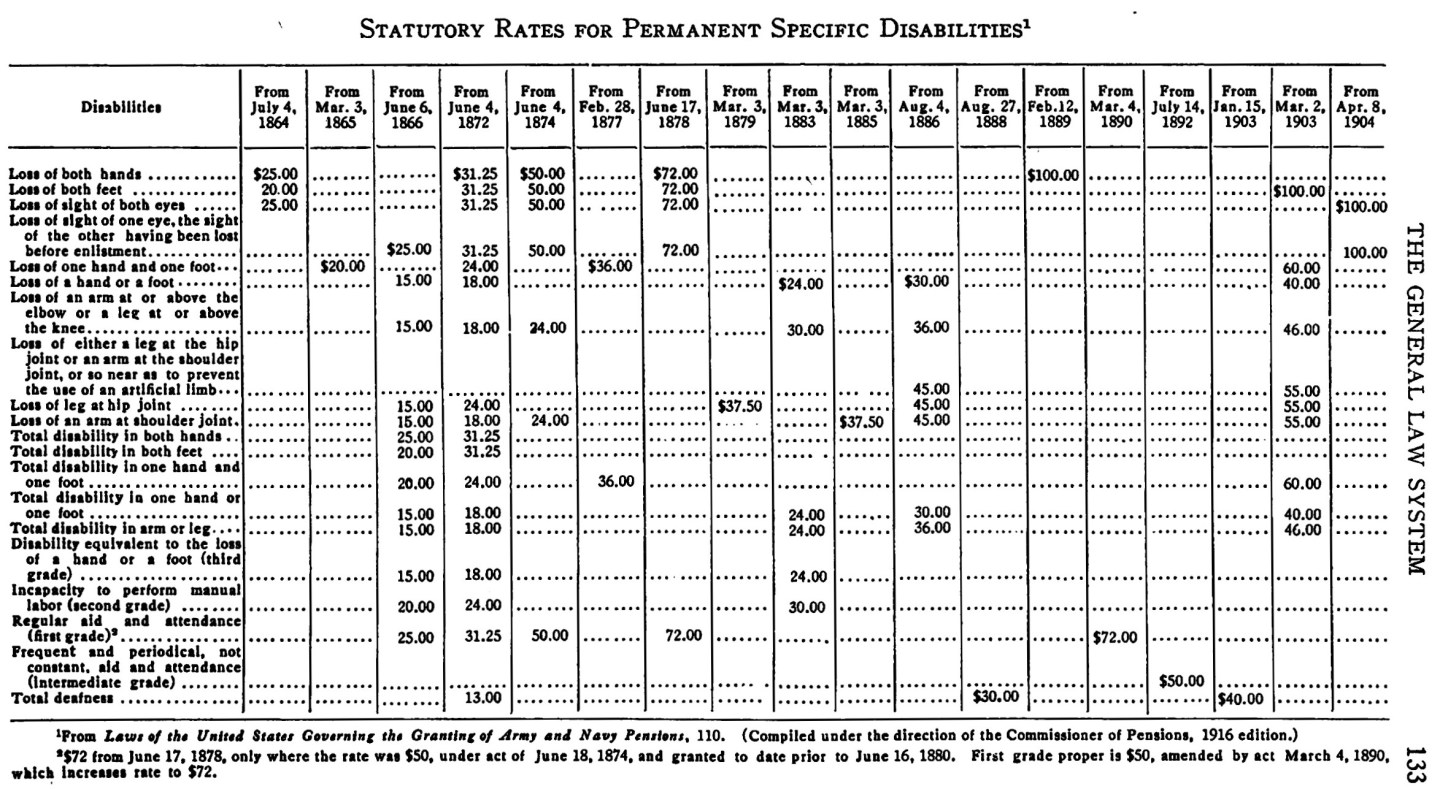

Congress diverged from this simple if highly subjective formula for calculating pension rates later in the war as casualties and the carnage on the battlefield mounted. In mid-1864, legislators approved an act establishing fixed rates that applied to all ranks for specific types of severe and permanent disabilities. The new law covered three conditions: the loss of both feet merited a monthly pension of $20 while the loss of both hands or the sight in both eyes was worth $25. Two additional laws passed in 1865 and 1866 added 14 other kinds of disabilities that qualified for a pension at a fixed rate of between $15 and $25. These rates were periodically increased in a series of later laws enacted between 1872 and 1904.

The modifications to the 1862 General Law were intended to provide clarity and consistency to the pension system, while also awarding more generous compensation to enlisted personnel and lower-ranking officers who suffered grievous injuries. But the new statutes introduced their own set of complications and ambiguities. Many of the disabilities covered were straightforward and simple to ascertain—for instance, loss of a leg at the hip joint or an arm at the shoulder joint earned the injured Veteran a monthly pension of $15. But the 1866 act also awarded $15—soon after increased to $18—for a “disability equivalent to the loss of a hand or foot,” a category of impairment that was open to interpretation. It also specified a payment of $20 for “incapacity to perform manual labor,” which seemed at odds with the terms of the 1862 law. An attempt to codify all existing pension laws in 1873 added another layer of complexity by empowering the Pension Bureau to establish fixed payment rates of between $1 and $17 for specific disabilities that fell short of being equivalent to the loss of a hand or foot.

Despite its shortcomings, the federal government applied the Civil War-era pension regulations to all who served in the U.S. Army and Navy after 1865, including those who fought in the Spanish-American War and Philippine Insurrection (1898-1902). When the United States entered World War I in 1917, however, Congress devised a different methodology for compensating service-connected injuries and placed it under the direction of a new agency in the Treasury Department, the Bureau of War Risk Insurance (BWRI). The BWRI calculated compensation for Great War Veterans according to a published rating schedule based on state workmen’s compensation laws. This process became the basis of the modern compensation system employed by VA today.

By Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D.

Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

American prisoners of war from World War II, Korea, and Vietnam faced starvation, torture, forced labor, and other abuses at the hands of their captors. For those that returned home, their experiences in captivity often had long-lasting impacts on their physical and mental health. Over the decades, the U.S. government sought to address their specific needs through legislation conferring special benefits on former prisoners of war.

In 1978, five years after the United States withdrew the last of its combat troops from South Vietnam, Congress mandated VA carry out a thorough study of the disability and medical needs of former prisoners of war. In consultation with the Secretary of Defense, VA completed the study in 14 months and published its findings in early 1980. Like previous investigations in the 1950s, the study confirmed that former prisoners of war had higher rates of service-connected disabilities.

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.