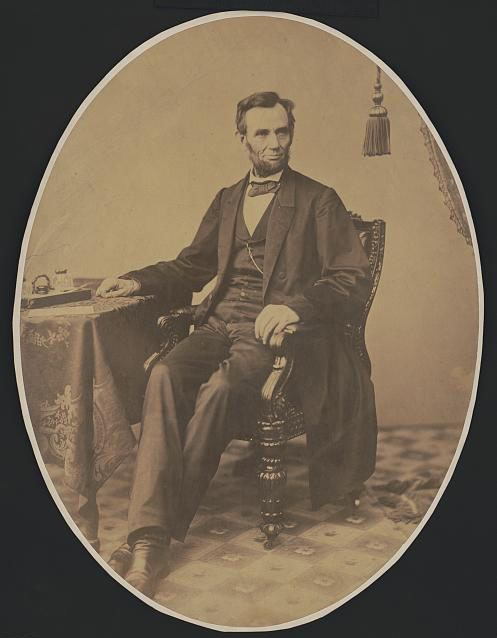

The President, his Gettysburg Address, and the national cemeteries are inextricably connected in American history

President Abraham Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address on November 19, 1863, on a battlefield near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Over three days of Civil War fighting on July 1-3 that year, more soldiers died here than any single battle fought in North America before or since. In just 272 words, Lincoln conveyed the importance of the proposition “all men are created equal” to America’s past, present, and future. Thousands had gathered to dedicate the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. His connection to the Department of Veterans Affairs is even deeper, as a portion of his promise to Veterans in his Second Inaugural address inspired VA’s motto.

The popularity of the sixteenth president, born on February 12, 1809, was rival only to President George Washington, the exalted father of the country and first person whose birthday, February 22, was designated a federal holiday. Lincoln was revered as the country’s savior, for reuniting the states by winning the Civil War.

State and unofficial recognition of Lincoln’s birthday had predated the expansive birthday program of 1909. But the centennial was big. The government and commercial interests produced readily accessible to a wide audience. Among the products Congress authorized was an order of seventy-seven Gettysburg Address tablets for placement in the national cemeteries. They were produced and delivered that year—but not in time for his birthday. “The delay was almost entirely due to difficulty in determining the text of the Gettysburg Address,” according to the [Washington, D.C.] Sunday Star (PDF, 1 page), because Lincoln had produced five versions of the speech. But on Memorial Day the government announced it would use the Col. Alexander Bliss (or Baltimore) version—the only copy dated and signed by Lincoln—to become the “standard use of the Lincoln Gettysburg Address.”1

The government also introduced common objects that would become ubiquitous: the Lincoln penny was the first U.S. coin to feature a historic figure; a 2-cent stamp with a portrait image based on an Augustus Saint-Gaudens sculpture was issued February 12, 1909. Sentimentality and popular culture emerged through, especially penny postcards, which were a relatively new, affordable, and popular means of writing to friends and family. At least three publishers promoted the Lincoln centennial by issuing colorful patriotic postcards. Another illustrates a facsimile of the standard Gettysburg Address tablet installed in national cemeteries in 1909.

Congress had authorized the cast-iron tablets in 1908. The cost, $3,000, is found in the War Department’s Report of the Chief of Ordnance of 1909-1911, which stated: “In the foundry and forge shop…a number of cast-iron tablets containing President Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address…have been made for placing in National Cemeteries.” Each tablet measures 56 inches tall and 33 inches wide, and weighs about 350 pounds. The most common paint scheme is a black background with white or silver letters and edging. Ornamental bolts were used to affix the tablets to metal posts in the cemetery landscape or on the wall of the superintendent’s lodge.

The U.S. Army’s Rock Island Arsenal in Illinois and the nearby Moline Scale Company produced the tablets, which are “one of the most interesting pieces of work—that is from a historical and patriotic standpoint, at least—ever executed by the company,” declared the [Davenport, IA] Daily Times. This meaningful object exists only because the nation observes Lincoln’s birthday, and the National Cemetery Administration (NCA) has upheld this commitment. For the bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth in 2009, NCA purchased sixty-two replica tablets and placed them in older cemeteries that did not have one, and in the more than forty new national cemeteries it has opened since 1973. One was used to replace a damaged tablet at Los Angeles National Cemetery; that historic tablet has been on display since 2018 in the lobby of VA headquarters in Washington, D.C.

The replicas, based on molds taken from a 1909 tablet, were also produced at Rock Island Arsenal. This project assured that Lincoln’s words and the tablet remains a relevant part of the cemeteries as the system continues to grow; as NCA builds new national cemeteries, the Gettysburg Address tablet is a required element. Learn more about these Gettysburg Address tablets at NCA History Program.

A note about the formidable presidential February birthdays: Congress in 1885 designated Washington’s birthday as a holiday for federal workers; Lincoln’s birthday was never so designated, though some states recognize it.2 In 1971, when the Uniform Monday Holiday Act went into effect, it moved federal observation of Washington’s birthday to the third Monday in February.3 That date, which falls between the two presidential birthdays, has unofficially become known as “Presidents Day.”4 A practical evolution this may be, but one that dilutes cultural memory along with the real birthdates of these remarkable leaders in American history.

Footnotes

- Lincoln spoke at the Baltimore Sanitary Fair, or Maryland State Fair for U.S. Soldier Relief, in spring 1864. He also provided a copy of the Gettysburg Address for inclusion in a book to be sold for fundraising, and Colonel Bliss was among those collecting material for the book. ↩︎

- Washington’s Birthday (Presidents Day) | National Archives. ↩︎

- By George, IT IS Washington’s Birthday! | National Archives. ↩︎

- George Washington and Abraham Lincoln – UM Clements Library (umich.edu) ↩︎

By Sara Amy Leach

Senior Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

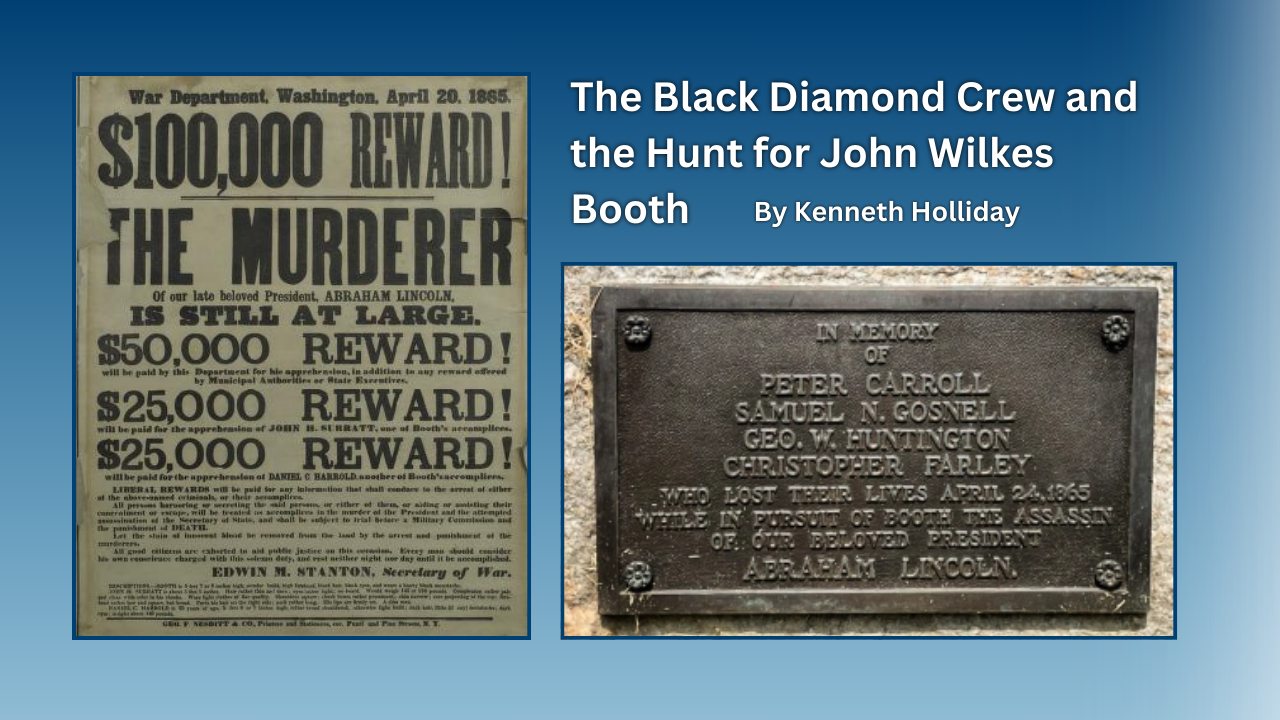

During the late evening, early hours of April 23-24, 1865, the Black Diamond, a ship on the Potomac River searching for President Abraham Lincoln's assassin John Wilkes Booth collided with another ship, the USS Massachusetts. The incident was a terrible accident during the frantic mission to locate the fleeing Booth before he escaped into Virginia. Unfortunately many lives were lost, including four civilians who had been summoned from a local fire department by the Army. For their assistance during this military operation, all four were buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery, some of the few civilians to receive that honor.

Featured Stories

In the mid-twentieth century, the lives of Dr. Ivy Brooks and Mildred Dixon, two trailblazing Black women physicians, converged at the Tuskegee, Alabama, VA Medical Center. Doctor's Ivy Roach Brooks and Mildred Kelly Dixon shared much in common. Both women were born in 1916 in the northeastern United States and received training in East Orange, New Jersey. They both launched careers in alternate medical professions before entering the fields of radiology and podiatry, respectively. Pioneering many “firsts” throughout their professional lives, both women faced and overcame the rampant racism and sexism of the era.

Featured Stories

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, American Expeditionary Force commander General John J. Pershing requested the recruitment of women telephone operators that were bi-lingual in English and French. Eventually 233 were selected out of over 10,000 applicants, and they served honorably through the war, earning the nickname of 'Hello Girls.'

However, their employment was not officially recognized as military service and therefore were neither honorably discharged, or eligible for the benefits other returning Veterans would receive. This kicked off a 60-year fight for 'Hello Girls' to receive legal Veteran status.