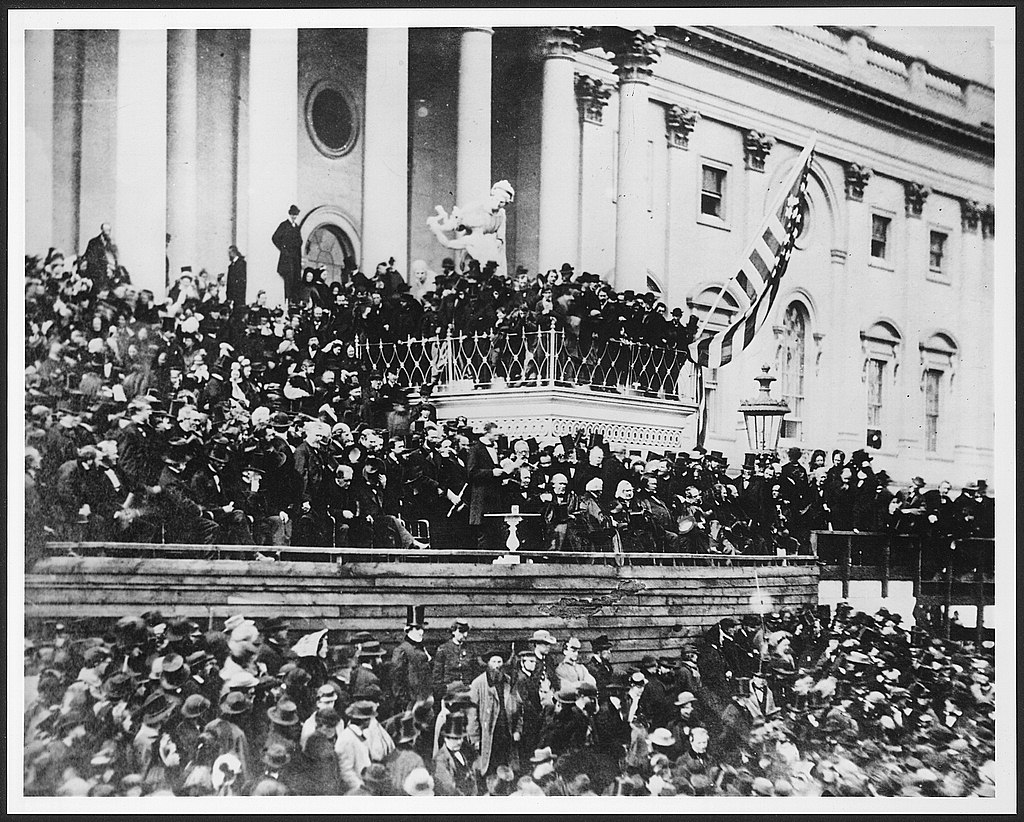

On March 4, 1865, as the Civil War entered its final weeks, President Abraham Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address from the East Portico of the U.S. Capitol. Four years earlier, he had stood in the same spot when he spoke to the crowd that had assembled for his swearing in as the sixteenth President of the United States. On that occasion, he talked at length about Constitutional principles and concluded with a plea for national unity in a desperate attempt to stave off a conflict that would claim the lives of over 600,000 Americans.

Now, in 1865, with the defeat of the Confederacy drawing near, Lincoln kept his remarks brief. At 700 words, his second address was only one-fifth as long as the first. But what the speech lacked in length, it more than made up for in power and eloquence. He denounced slavery as a stain upon the land and characterized the war as a form of divine retribution to wash away the nation’s sins. He ended his address with a stirring call for healing and reconciliation, to which he added a solemn promise to those who had fought to restore the Union:

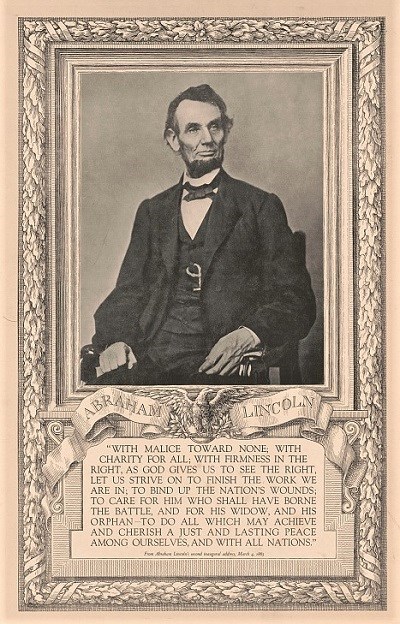

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

Lincoln did not live to see whether his hopes for a harmonious future for the nation would be realized. An assassin’s bullet ended his life just days after the Confederate Army surrendered at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. However, at the time of his death, the government had already taken steps to fulfil his pledge to Union Veterans and their families. In 1862, Congress passed a generous pension law that compensated soldiers not only for their injuries, but also for illnesses sustained in military service. The same year, Congress authorized the establishment of national cemeteries for the burial of Union war dead. And the day before Lincoln took the oath of office for the second time, he signed into law a bill creating a national soldiers and sailors asylum. The first of these homes opened in 1866. Over the next fifty years, the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers would grow into a network of residential communities at eleven different locations around the country.

Lincoln’s second inaugural address was destined to become his second most famous speech, surpassed in popularity only by the 1863 Gettysburg Address. Almost a century later, his appeal “to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan” inspired Sumner Whittier, the head of the Veterans’ Administration (the forerunner of the Department of Veterans Affairs), to adopt those words as VA’s motto. In 1959, they were inscribed in all capital letters on two plaques mounted to either side of the entrance to VA’s central office in Washington, D.C. Prominently displayed in this fashion, they reminded all who entered the building or passed within eyeshot of the nation’s enduring obligation to those who served. In 1999, Lincoln’s words also were incorporated into VA’s mission statement, encapsulating in succinct but poetic terms the agency’s commitment to caring for Veterans and their dependents.

Note: In 2023, VA revised its mission statement, reframing Lincoln’s words with more inclusive language to read: “To fulfill President Lincoln’s promise to care for those who have served in our nation’s military and for their families, caregivers, and survivors.”

By Barbara Matos, Executive Assistant, Office of Procurement Policy, Systems and Oversight, and Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D., Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 100: Burn Pits 360 Logo

A year after returning from Iraq with severe respiratory problems in 2008, Capt. Le Roy Torres and his wife founded Burn Pits 360 to raise awareness of the health hazards of burn pit emissions. Over a decade of persistent advocacy by Burn Pits 360s and other Veterans groups paid off with passage of the PACT Act in 2022, the largest expansion of Veterans benefits since the 1944 GI Bill.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 99: Bank Check from Manila Loyalty Room

After World War II, U.S. Army investigators in the Philippines turned over a huge collection of captured documents, intelligence reports, press clippings, and Japanese banks checks to the VA office in Manila. The Manila office stored the collection in the “Loyalty Room,” so named because VA used the checks and other records to evaluate the wartime allegiance of Filipino Veterans applying for benefits.