Following the Civil War, the United States was left with historic devastation as an estimated 360,000 Union soldiers and 260,000 Confederate soldiers lost their lives in the conflict. Many Veterans were left with severe injuries, some life-altering.[1] To care for Union Veterans, Congress authorized the establishment of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (National Home).

The idea for establishing a domiciliary and hospital for Union Veterans was generated by Delphine Baker, a volunteer nurse during the Civil War in both Chicago and St. Louis. At the time, organizations like the U.S. Soldiers Home in Washington, D.C. and the Naval Home in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania housed officer and career Veterans, but not volunteer servicemen. Unique in its mission, the National Home served all volunteer soldiers. [2]

Characterized by an independent spirit, Baker transported supplies from her city to nearby hospitals to support the war effort. In poor health, she had to discontinue this practice in 1861. By 1862 she had developed a new way to help the Union cause through the development of the National Banner, a monthly journal that published pieces on literature, science, and art and used its profits to assist injured soldiers and Veterans.[3] Two years later in 1864 she moved to New York and established the National Literary Association which continued the mission of the National Banner on a larger scale.

Through the Association, Baker began galvanizing support for the creation of a national home for disabled Civil War soldiers, gaining the approval of Henry Longfellow, Clara Barton, Horace Greeley, and even Ulysses S. Grant.[4] The petition gained over one hundred signatures, leading to its introduction to Congress on March 1, 1865. Introduced by Senator Henry Wilson, the chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs and the Militia, it was described as “a little bill to which there can be no objection.”

Just two days later, on March 3, the bill passed. A strong supporter of Veterans, President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill into law the same day. Just one year later in 1866, the first National Home was opened in Togus Springs, Maine. Two more were established a year later in Dayton, Ohio and Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[5]

The Dayton campus, also known as the Central Branch, officially opened on March 26, 1867 and Perry Trudden was admitted as the first resident.[6] With Thomas B. VanHorne as the landscape architect, the Central Branch of Dayton, Ohio began to take shape with the 627-acre home becoming a tourist attraction which drew 100,000 visitors annually as of Henry Howe’s recollections in 1888.

The structure of the Dayton home was familiar to Veterans considering it was constructed in a similar fashion to military installations. As the campus expanded, multiple buildings with 19th and 20th Century architecture styles were added.[7] Standing out prominently on the campus is the Gothic Revival Protestant Chapel, which is one of the 28 pre-1930 buildings still standing today and the first stand-alone church at a National Home.[8] The grounds were impeccably fashioned, complete with a grotto and exotic animals including swans and alligators.[9]

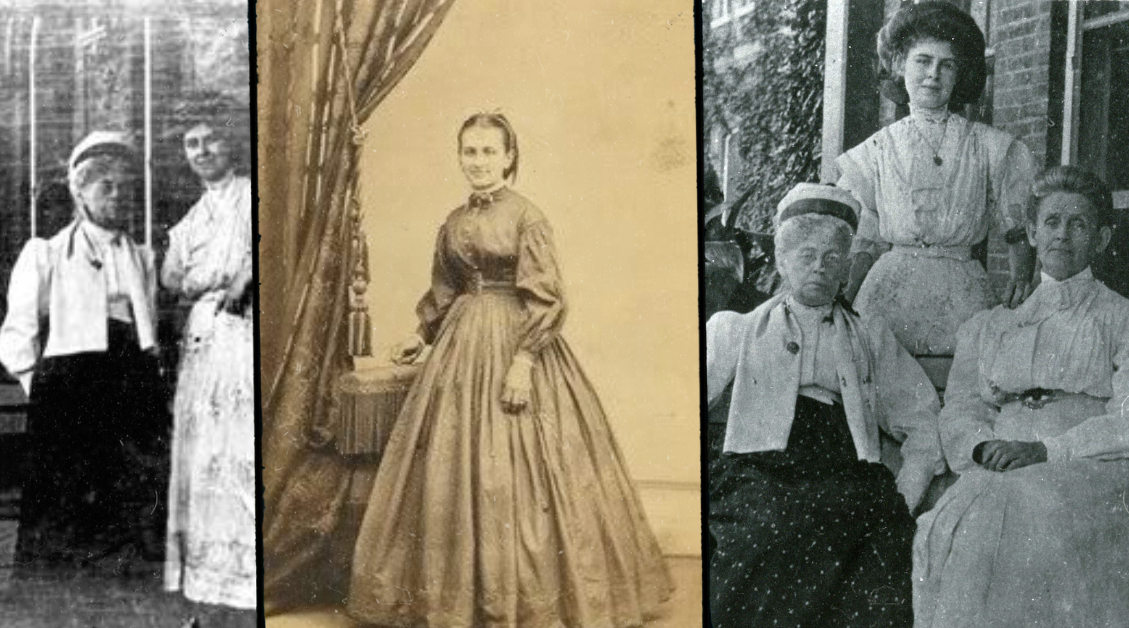

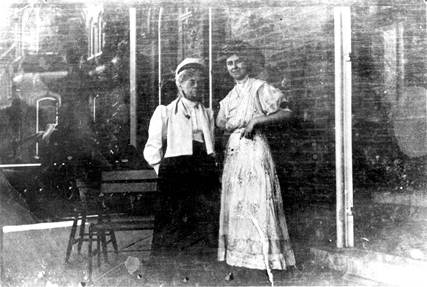

Keeping the Home in line was Emma Miller, a devoted caretaker of Civil War Veterans who served as the Matron, the first woman to hold such a position. After the loss of her husband in the Civil War, Miller worked closely with a civilian-run group, the U.S. Sanitary Commission, to help returning Veterans and their families. When the Central Branch home was opened, she was appointed as Matron. [10] Known for her great care, Miller was a perfect fit for the position at the newly opened Dayton Home. In this capacity, Miller oversaw the daily necessities to keep the Home functioning, including securing food, taking stock of rations, restocking hospital supplies, overseeing distribution of goods, and cleaning.[11]

The “Little Mother” of the Home was eventually promoted to Superintendent of the General Depot, meaning Miller facilitated the manufacturing and distribution of supplies for Homes across the Nation. Her success led to her appointment to the Board of Managers of the National Home system.[12] Upon her death in 1914, Miller received full military honors at her funeral, the only civilian to have such an honor.[13] Later the first dormitory for women Veterans at Dayton was named in her honor.

Reflecting on her contributions, Colonel White, governor of the Home wrote, “She showed through her long period of service to the nation she loved a faithfulness, devotion, and efficiency which would do credit to any soldier that every fought for the flag.”[14]

Through the vision and foresight of two women, Delphine Baker and Emma Miller, the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers system was established and maintained. With their leadership, generations of Veterans were cared for and supported, ensuring they received the best care possible following their service to the Nation and establishing the basis for today’s system of Veteran hospitals.

[1]. “Civil War Soldiers’ Stories,” LOC, Library of Congress, accessed March 2, 2023, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/civil-war-and-reconstruction-1861-1877/civil-war-soldiers-stories/.

[2]. Trevor K. Plante, “The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers,” Prologue Magazine, vol. 36, no. 1 (Spring 2004), https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2004/spring/soldiers-home.html.

[3]. “Delphine Baker: Advocate for the Soldiers’ Home for Civil War Veterans,” Women History, accessed March 8, 2023, https://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2008/03/delphine-baker.html.

[4]. “Delphine Baker Access Ramp,” The American Veterans Heritage, American Veteran’s Heritage Center, accessed March 8, 2023, https://americanveteransheritage.org/what-we-do/grotto-gardens/tour.html/title/7-delphine-baker-access-ramp.

[5]. Trevor K. Plante, “The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers,” Prologue Magazine, vol. 36, no. 1 (Spring 2004), https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2004/spring/soldiers-home.html.

[6], “History of the VA Center, Dayton, Ohio,” Dayton History Books, Dayton History Books Online, accessed July 13, 2021, https://www.daytonhistorybooks.com/page/page/5086090.htm.

[7], “A Nation Repays Its Debt: The National Soldiers’ Home and Cemetery in Dayton, Ohio,” National Park Service, National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior, accessed July 13, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/articles/a-nation-repays-its-debt-the-national-soldiers-home-and-cemetery-in-dayton-ohio-teaching-with-historic-places.htm.

[8]. “Central Branch Dayton, Ohio,” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, accessed March 21, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/places/central-branch-dayton-ohio.htm.

[9]. Suzanne Julin, “National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers Assessment of Significance and National Historic Landmark Recommendations,” NPS History, National Parks Service History eLibrary, accessed September 3, 2021, http://npshistory.com/publications/nhl/special-studies/national-home-disabled-vol-soldiers.pdf.

[10]. “Emma Miller — VHA’s First Female Employee — Forged a Path for Today’s Women Leading HPO Programs,” VA Homeless Programs, US Department of Veterans Affairs, last modified March 15, 2021, accessed March 1, 2023, https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/updates/2021-03-15-Emma-Miller-VHAs-First-Female-Employee.asp.

[11]. “1885, NHDVS Investigation,” VA History Office files.

[12]. “Little Mother of Soldiers Dies at Soldiers’ Home,” The Dayton Journal, 1914 and “Emma Miller — VHA’s First Female Employee — Forged a Path for Today’s Women Leading HPO Programs,” VA Homeless Programs, US Department of Veterans Affairs, last modified March 15, 2021, accessed March 1, 2023. https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/updates/2021-03-15-Emma-Miller-VHAs-First-Female-Employee.asp.

[13]. “Emma Miller — VHA’s First Female Employee — Forged a Path for Today’s Women Leading HPO Programs,” VA Homeless Programs, US Department of Veterans Affairs, last modified March 15, 2021, accessed March 1, 2023, https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/updates/2021-03-15-Emma-Miller-VHAs-First-Female-Employee.asp.

[14]. “Little Mother of Soldiers Dies at Soldiers’ Home,” The Dayton Journal, 1914

By Parker Beverly

VA History Office intern and Wake Forest undergraduate student

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."