Unlike previous wars, the federal government in the Civil War arranged to care for returning soldiers too weakened by their wounds, the lingering effects of disease, or the hardships of military life to care for themselves. In the decades after the war, the government established a network of eleven residential facilities known collectively as the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. First reserved for Union Veterans, the National Homes eventually admitted former soldiers and sailors of any conflict save for those who fought for the Confederacy.

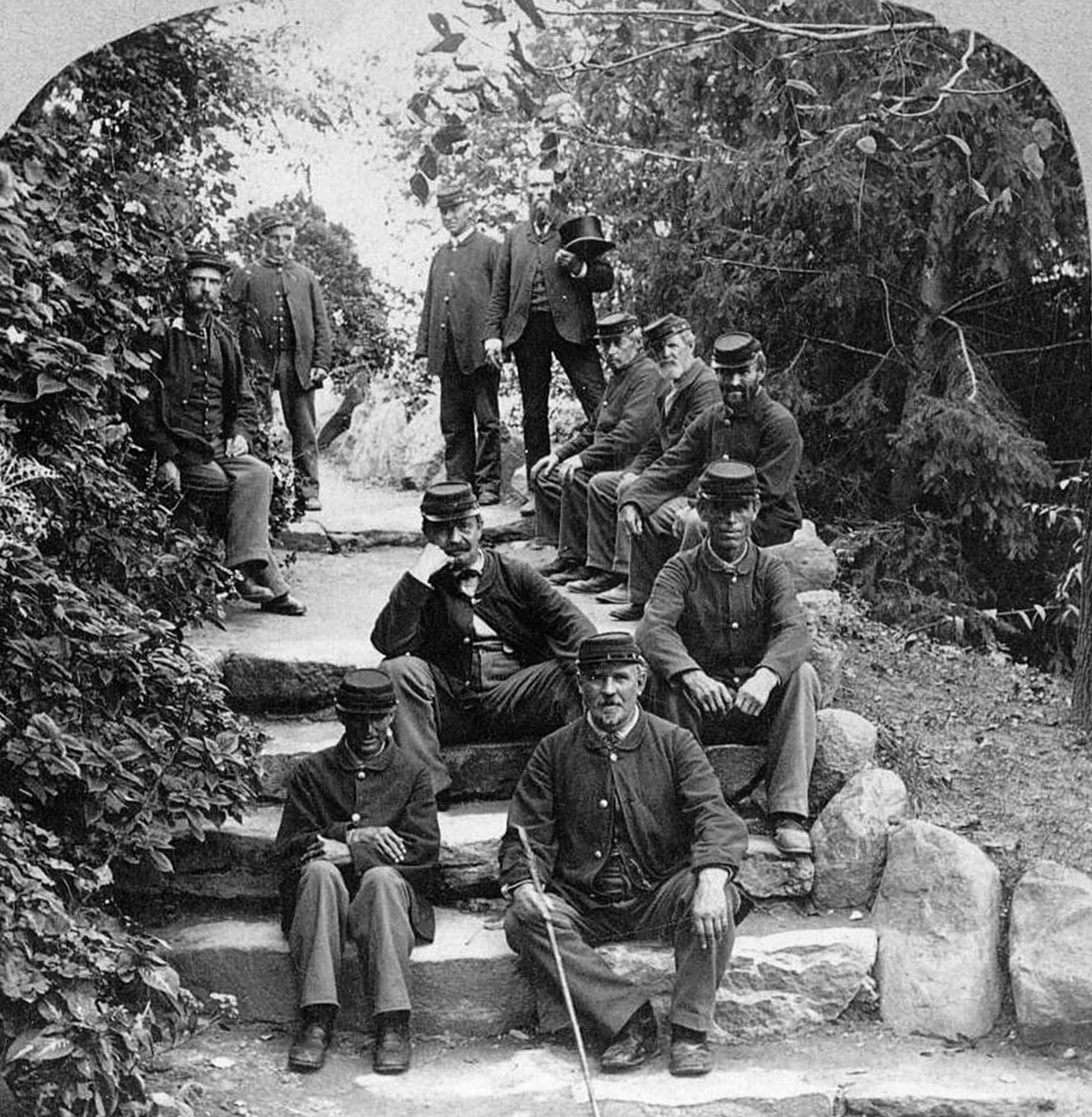

National Home branches were organized along military lines. Residents lived in barracks, ate in mess halls, wore uniforms, and followed Army regulations. At the same time, the Board of Managers for the National Home sought to invest the sites with many of the trappings of home and community, adding such amenities as chapels, libraries, theaters, and playing fields. Great care also went into the shaping of the physical environment. The board employed landscape architects to design the grounds of each branch to create an attractive, idyllic setting for residents and visitors alike. Influenced by the picturesque landscape movement, they adorned the National Home campuses with man-made ponds and lakes, ornate flower gardens, elaborate plantings of shrubs and trees, winding trails, and other features to beautify the properties.

The Central Branch in Dayton, Ohio, exemplifies the landscape architecture at the National Homes. It opened in 1867, joining the Northwestern Branch in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and the Eastern Branch in Togus, Maine, as the first three sites in the National Home system. The Board of Managers located the branch on several hundred acres of farmland three miles west of Dayton’s downtown. Thomas B. Van Horne, an experienced landscape architect who served as a chaplain in the Union Army during the Civil War, created the layout for the grounds here as well as at the Milwaukee Home. The Dayton campus had a military bearing, with barracks arranged in orderly rows adjoining the western side of the central parade ground. But Van Horne turned the eastern part of the property into a scenic park. Walking paths encircled the four artificial, spring-fed lakes that were formed by widening and deepening the pits left by the limestone quarried for building material. Groves of trees, decorative gardens, patterned flower beds, and a rock grotto with waterfall and drinking springs also graced this side of the campus.

One of the earliest residents, Frank Mundt, was a florist and gardener by trade and he scoured the surrounding countryside for wildflowers and vines, which he then transplanted to the grotto area to luxuriant effect. Residents also cultivated many species of exotics plants and flowers in the Home’s two conservatories for display on the property. Over time, the Dayton Home supplemented the splendors of the natural world with creatures from the animal kingdom, establishing a zoological garden that included an aviary for birds, a deer park, and an alligator pond. At the height of the Home’s popularity around the turn of the century, over 500,000 people turned out annually to tour the grounds and view the wildlife menagerie and other sights.

While not quite as big of a draw as Dayton, the other branches of the National Home also attracted thousands of visitors from the surrounding areas. Their aesthetically pleasing grounds, gardens, and waterways offered visitors a welcome refuge from city life and a public space to experience and enjoy nature. Many sightseers arrived by rail, trolley, or streetcar lines that connected the National Home sites to the nearby urban centers. Some branches also built hotels to accommodate guests who wished to stay overnight. The popularity of the National Homes as a tourist destination strengthened the ties between the Veterans and the local citizenry and integrated the branches into the social and economic life of the neighboring communities. Of course, the pleasures of wandering the carefully manicured campuses or picnicking by one of the man-made lakes were not reserved for visitors alone. The Veterans themselves enjoyed the therapeutic benefits of living in a wholesome environment with the attractions of nature close at hand. Many of the more able-bodied men also played a direct role in the upkeep of the grounds, tending the gardens and assisting with other beautification projects.

After World War I, the National Home branches were incorporated into the expanding hospital system for Veterans overseen by the Veterans Administration. Their populations dwindled over time as the focus of these facilities shifted to in-patient medical care rather than long-term residential services. The physical appearance of the campuses also changed as old construction was replaced with new and the ornamental landscaping features that once delighted visitors deteriorated or disappeared. The VA Medical Center in Milwaukee that now occupies the site of the Northwestern branch, for instance, retains only one of its four original lakes while the VA medical facility at the old Danville, Illinois, Home drained its lake and replaced it with a golf course. The grotto and gardens at Dayton also suffered from neglect and became badly overgrown. In recent years, however, the grotto has been renovated and a dedicated corps of volunteers has restored the floral gardens to something of their former glory.

For more on this subject, visit our digital exhibit Landscaping and Architecture at the National Home.

Note: This story was originally posted under a different headline and lead image. This was updated on Dec. 12, 2023 to its current form.

By Maureen Thompson, Ph.D., Historian, Central Alabama VA Medical Center-Tuskegee and Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D., Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.

History of VA in 100 Objects

After World War I, claims for disability from discharged soldiers poured into the offices of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the federal agency responsible for evaluating them. By mid-1921, the bureau had awarded some amount of compensation to 337,000 Veterans. But another 258,000 had been denied benefits. Some of the men turned away were suffering from tuberculosis or neuropsychiatric disorders. These Veterans were often rebuffed not because bureau officials doubted the validity or seriousness of their ailments, but for a different reason: they could not prove their conditions were service connected.

Due to the delayed nature of the diseases, which could appear after service was completed, Massachusetts Senator David Walsh and VSOs pursued legislation to assist Veterans with their claims. Eventually this led to the first presumptive conditions for Veteran benefits.