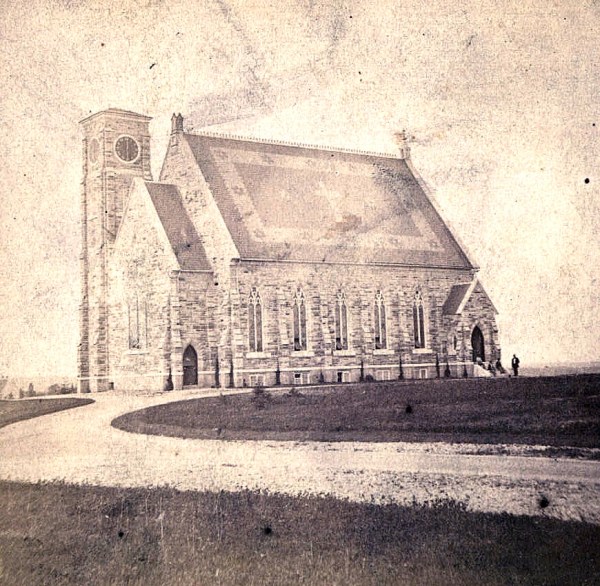

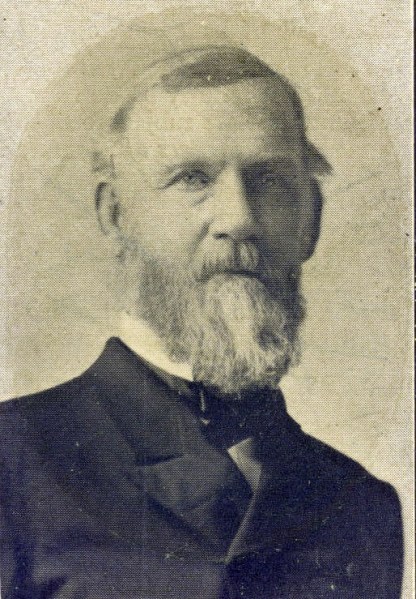

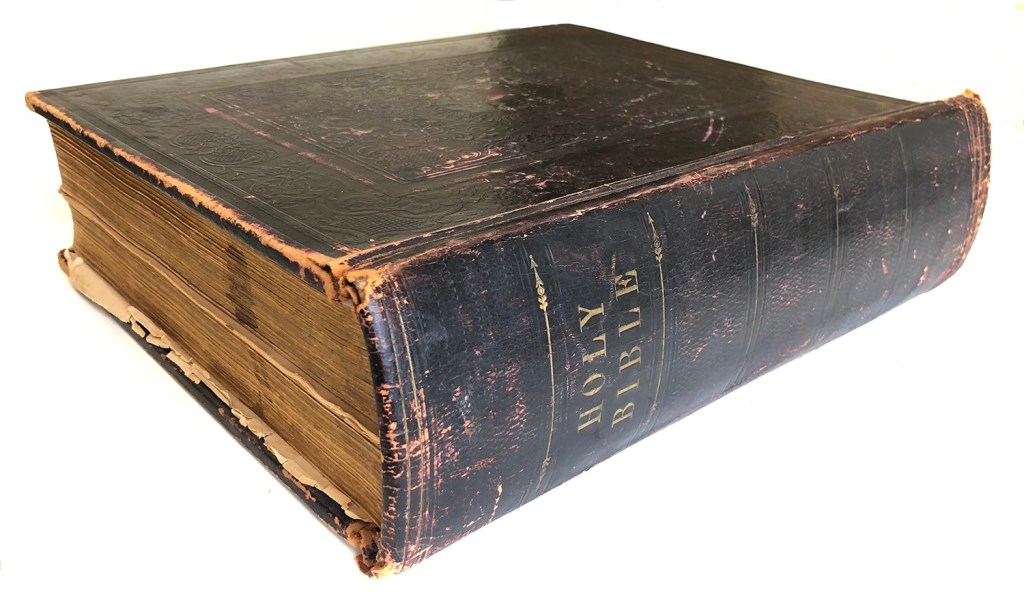

While many stories in the Bible have resonance for readers, the Book of Job held extra meaning for Civil War Veterans living at the Central Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (NHDVS) in Dayton, Ohio. The 1861 edition of the Dayton Bible that was used in countless services at the chapel displays telltale color changes to certain pages due to light exposure and cracking along one part of the binding. These blemishes suggest that it was frequently opened to the chapters relating Job’s story. The sermons given by Reverend William B. Earnshaw about Job, a righteous man tested beyond measure, must have provided relief and comfort to the ex-soldiers who had witnessed and endured the horrors of battle.

The Dayton Bible highlights the important role that religious faith and chaplains played in the lives of the National Home residents as well as later generations of Veterans. When the NHDVS system was established in 1867, chaplains like Earnshaw were provided housing on the different National Home campuses and paid a salary of $1,500 per year plus forage for one horse. Religious services were held for both Protestant and Catholic Veterans and large weekly attendance numbers resulted in “much good, and largely contributed to the moral improvement of the mend and the peace and good order of the establishment.”

As the network of Soldiers Homes and later Veterans hospitals expanded across the nation in the early 1900s, ministry became a largely part-time affair performed by civilian clergy from the surrounding community. World War II changed everything, as sixteen million Veterans returned home, many needing medical assistance from the Veterans Administration. VA established a Chaplain Service in 1945 in the Department of Medicine and Surgery and named Reverend Crawford W. Brown, a former Army chaplain, as its first director. In the post-World War Two period, as the service was formalized, it added chaplains of different faiths and became an integral part of the care Veterans received at VA facilities. Chaplains made rounds, providing counseling and comfort to patients. They also led services in hospital chapels.

In 1964, the Veterans Administration Chaplain School was established at the Jefferson Barracks VA Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri, to better equip and train chaplains to meet the specific needs of Veterans. Today, there are over 800 full- and part-time chaplains representing a spectrum of religious faiths and traditions. Furthermore, every VA hospital contains a chapel for reflection and services. While the program has grown and evolved from the earliest days of Reverend Earnshaw’s ministry, the mission remains largely the same as it was in the 1870s: “To assure Veterans and their families the best possible spiritual guidance, religious services, and care.”

Reflecting its significance, the Dayton Bible was selected as the first object to be officially placed into the collection of the National VA History Center in 2021. The chapel where Reverend Earnshaw once preached from that copy of the Bible about the trials of Job still serves as a house of worship for Veterans and their families of the Protestant religion.

By Katie Rories

Historian, Veterans Health Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

American prisoners of war from World War II, Korea, and Vietnam faced starvation, torture, forced labor, and other abuses at the hands of their captors. For those that returned home, their experiences in captivity often had long-lasting impacts on their physical and mental health. Over the decades, the U.S. government sought to address their specific needs through legislation conferring special benefits on former prisoners of war.

In 1978, five years after the United States withdrew the last of its combat troops from South Vietnam, Congress mandated VA carry out a thorough study of the disability and medical needs of former prisoners of war. In consultation with the Secretary of Defense, VA completed the study in 14 months and published its findings in early 1980. Like previous investigations in the 1950s, the study confirmed that former prisoners of war had higher rates of service-connected disabilities.

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.