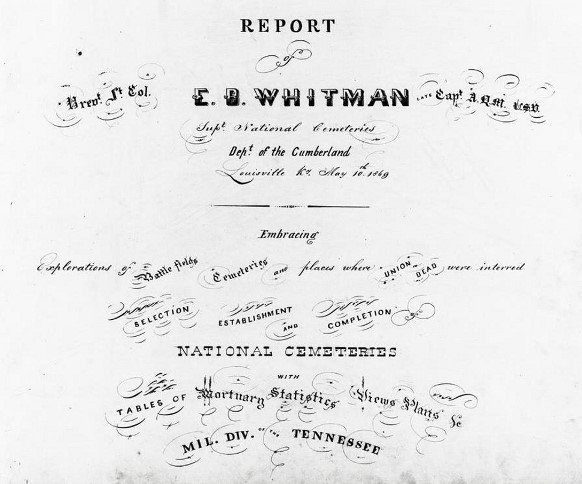

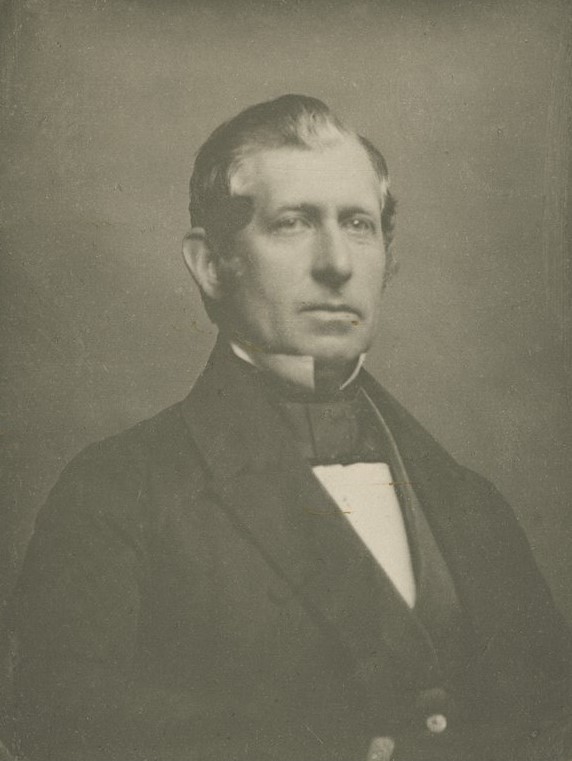

The U.S. Army’s plan for the recovery of Union dead across the battle-ravaged South after the Civil War came about through the labors of a remarkable if little known officer, Edmund B. Whitman. He spent four years overseeing the collection of thousands of remains and creating “mortuary records” of reburials in new national cemeteries. After completing his “Harvest of Death,” to use his phrase, he produced in 1869 an extraordinary report that recounted the breadth, sequence, and challenges of his reinternment mission.

The mortuary statistics contained within the report’s 130-plus pages are important, but the illustrations are no less valuable. The artwork includes sketches and plats of twenty national cemeteries, as well as individual “cemeterial district” maps showing where the dead were found and subsequently reburied. Whitman had some experience doing this kind of work. The Harvard College graduate was an educator in the East until 1855, when he moved to Kansas Territory as a representative of the New England Emigrant Aid Society. In the late 1850s, he partnered with Albert D. Searl to survey and map farms, railroads, and make “town plats, and historical views of scenes.”

Whitman was 49 when he enlisted in the Union Army in July 1862. Appointed a captain and assistant quartermaster, he spent the war years in Tennessee and its environs. In December 1865, Major General George H. Thomas tasked Whitman with “visiting battle-fields, cemeteries, and places where Union dead are interred” throughout the Department of the Cumberland, which encompassed Tennessee and Kentucky, as well as parts of Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. He set out on his first expedition through this territory on March 1, 1866, accompanied by officers, soldiers, and clerks. Promoted to brevet major in June 1866, Whitman was given the additional responsibility of “locating, purchasing, and establishing National Cemeteries, and preparing Mortuary Records.” The disinterment of remains began in October. In January 1867, Whitman was named Superintendent of National Cemeteries. Although his appointment applied only to the Department of the Cumberland, the system he developed was adopted nationally.

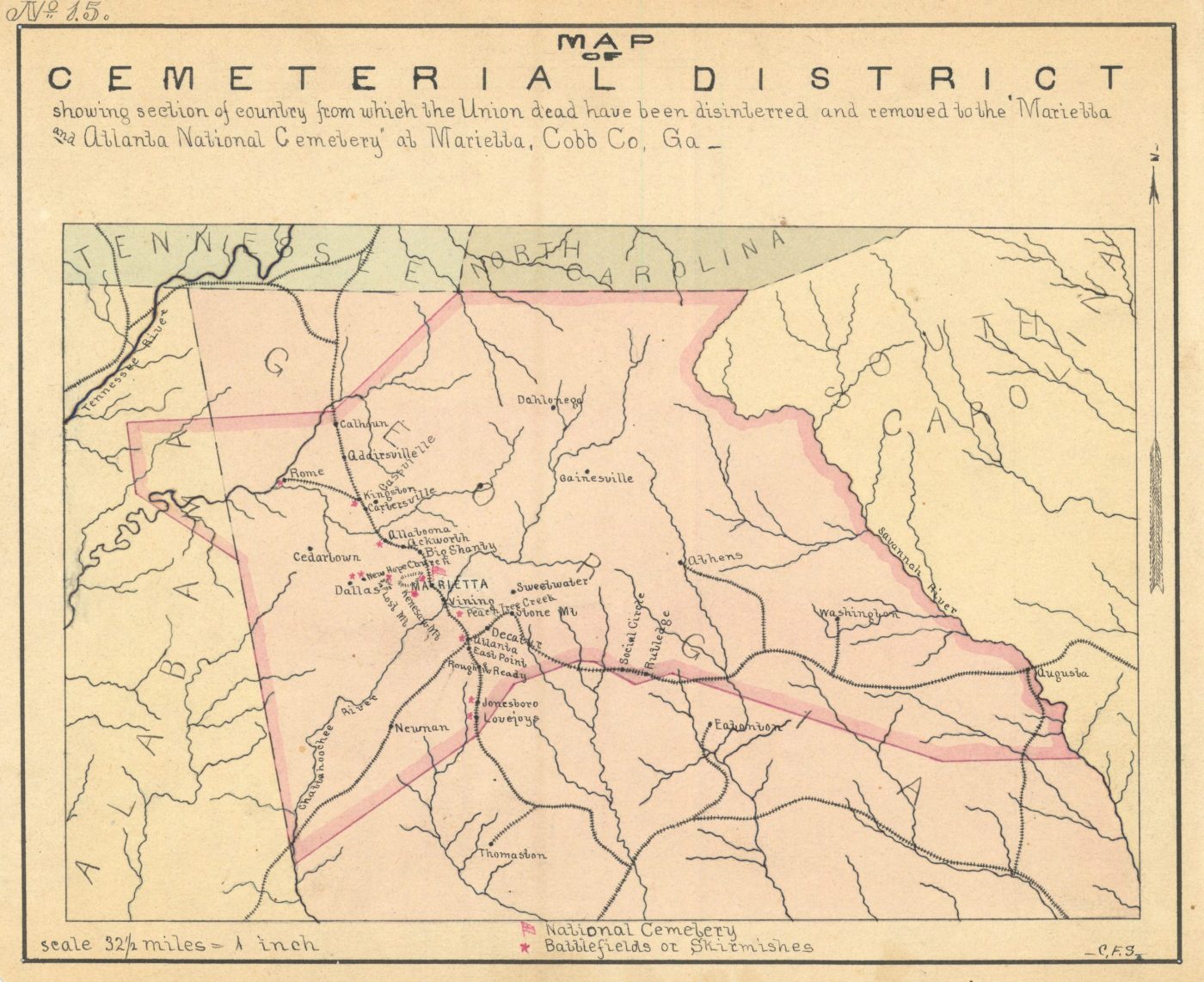

Whitman identified four “principles which should govern in the selection of national cemetery sites”: 1) “Distinguished localities, of great historical interest” to honor the Union’s sacrifice; 2) “points conspicuous . . . on the great thorough-fares of the nation”; 3) “central points, convenient of access”; and 4) “favorable conditions for ornamentation, so that surviving comrades, loving friends, and grateful States, might be encouraged to expend liberally of their means, for such purposes.” These criteria were reflected in the “cemeterial districts” Whitman delineated after three major expeditions and several shorter trips in search of the dead. Charles F. Smith drafted individual maps of the two dozen or so districts; these were published separately from the final report. Diminutive, delicate, and inked in black with pink, green and other pastel watercolors, they show geographic features and, in red ink, a flag at the cemetery. Their cheery appearance belies the human loss they illustrate.

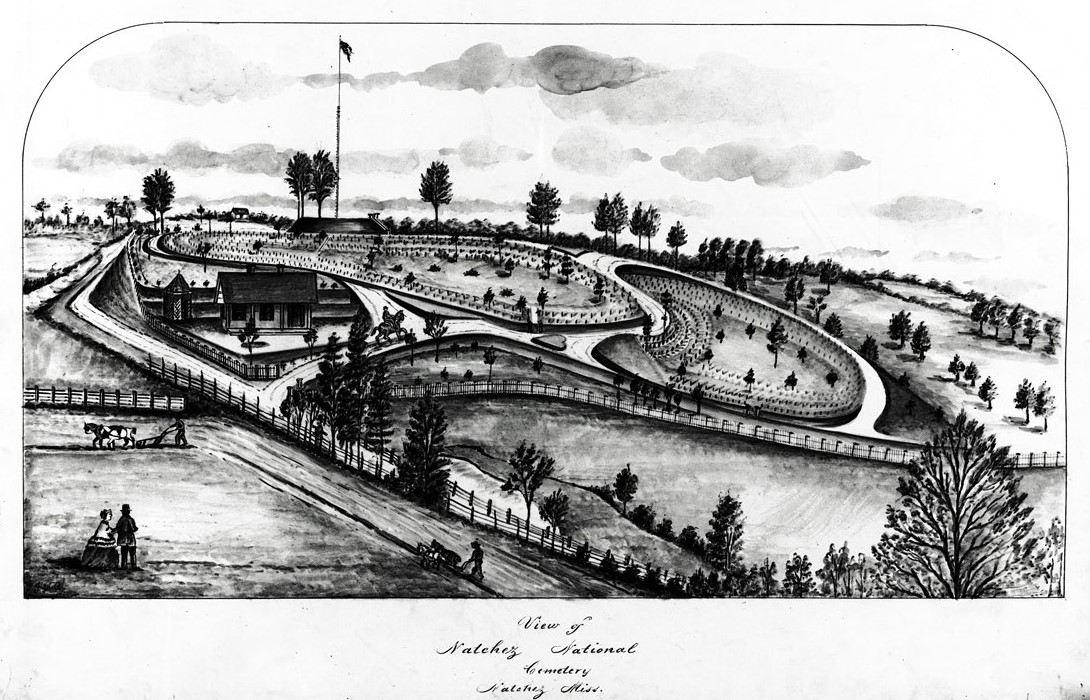

In the report proper, technical “surveys [and] elaborate sectional plats” were paired with charming and imaginative cemetery views from the perspective of approaching pedestrians. Philip M. Radford, a Nashville-based civil engineer, produced the eighteen sketches. Since photographs of national cemetery landscapes in the late 1860s are scarce, Radford’s work offers a rare view of the early construction in the cemeteries, wooden structures such as lodges, a “head board house,” and a “pump” (well) shelter.

Collectively, the plats are notable for illustrating one-quarter of all the national cemeteries established by 1872 when reburials were complete. The Army did not produce a national cemetery atlas until 1892-1893. Individually, the plats show the range of designed landscapes and how the dead were buried in sections, by state, enlisted and officer, Black and White. No federal policy about posthumous segregation has been found for this era, but Whitman was clear that he would not tolerate the practice. “No distinction is to be made in regard to color so far as the removal to the National Cemeteries is concerned,” he wrote in 1867. “[Black troops] are in every way, to be treated as if they were white soldiers.” The war created more unknown dead than any U.S. conflict. Remains that could not be identified were buried together. Whitman observed that this was the most sorrowful outcome for the government, the men who sacrificed their lives, and their loved ones.

Whitman quantified the results of his work. His men visited nearly 2,000 localities, found in excess of 40,000 scattered graves, and recorded more than 10,000 names. They collected remains from “no less than 6,283 distinct spots” and reinterred more than 114,500 remains into national cemeteries within the Military Division of the Tennessee. He mustered out of the Army on July 15, 1868, at the rank of brevet lieutenant colonel, but he spent another year as a civilian producing this report, which “formed the basis of the elaborate system of National Cemeteries.” His efforts led to passage of the 1867 National Cemetery Act, the first substantive legislation to define these shrines and provide permanent grave markers to honor service members. Whitman’s accomplishment, handsomely illustrated in this report, was echoed in a Society of the Army of the Cumberland eulogy: “The beautiful cemeteries of the Southern States will remain a perpetual memorial of Colonel Whitman.”

This report and individual district maps are part of the U.S. Army Quartermaster records (RG 92) at the National Archives facilities in Washington D.C., and College Park, Maryland, respectively.

By Sara Amy Leach

Senior Historian, National Cemetery Administration (Retired)

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.

History of VA in 100 Objects

After World War I, claims for disability from discharged soldiers poured into the offices of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the federal agency responsible for evaluating them. By mid-1921, the bureau had awarded some amount of compensation to 337,000 Veterans. But another 258,000 had been denied benefits. Some of the men turned away were suffering from tuberculosis or neuropsychiatric disorders. These Veterans were often rebuffed not because bureau officials doubted the validity or seriousness of their ailments, but for a different reason: they could not prove their conditions were service connected.

Due to the delayed nature of the diseases, which could appear after service was completed, Massachusetts Senator David Walsh and VSOs pursued legislation to assist Veterans with their claims. Eventually this led to the first presumptive conditions for Veteran benefits.