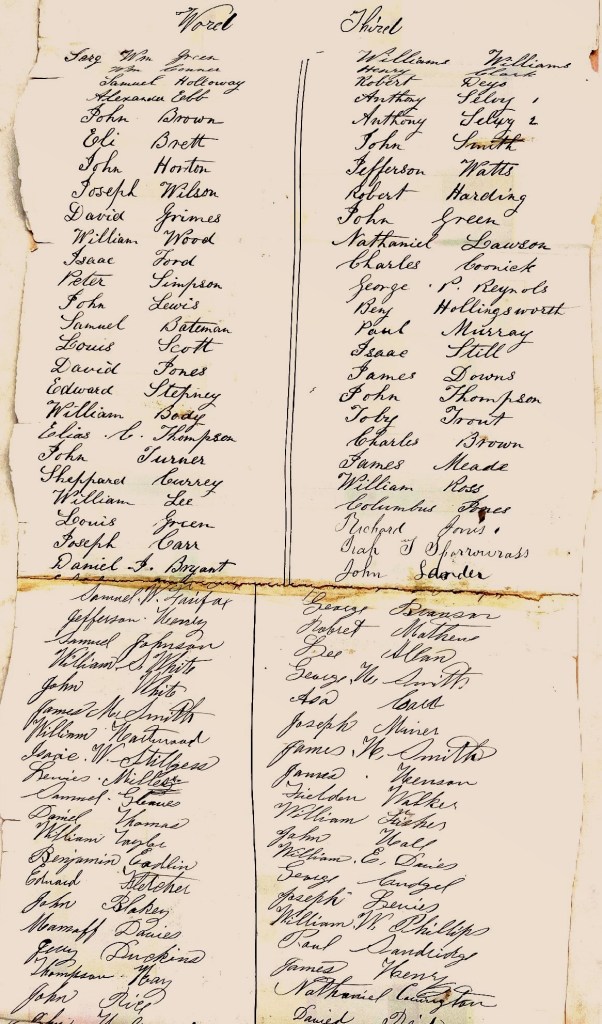

Just after Christmas in 1864, African American soldiers recuperating at the United States Colored Troops (USCT) L ‘Overture General Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia, submitted a petition for the right to burial alongside their White counterparts in the city’s Soldiers’ Cemetery, one of the first national cemeteries established by the U.S. government during the Civil War. To accompany the petition, the aggrieved soldiers included their names—443 in total—arranged by hospital ward and pasted together into a single roll that stretched nearly ten feet in length when unfolded.

Alexandria’s proximity to the nation’s capital, along with its railroads and Potomac River access, made it a key strategic military center and a place of sanctuary for those who had escaped slavery. The Union Army quickly occupied the city after Virginia seceded and it became the hub from which food, ammunition, forage, and soldiers traveled to Virginia battlefields. It also became a hospital center for sick and wounded soldiers from those battlefields. Numerous “contrabands”—the U.S. government’s designation for formerly enslaved African Americans who took refuge behind Union lines—congregated in the city as well. Black Union soldiers became a presence after President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, permitting the War Department to enlist African Americans without restriction in USCT regiments.

Much of the military activity in Alexandria centered around the Army’s Quartermaster Department, which was responsible for moving and supplying troops. Brevet Colonel James C. Lee supervised Alexandria’s quartermaster activities from 1863 to 1866. One of his duties was overseeing the burial of military dead in the area. Albert Gladwin, a White Baptist minister from the North who served as Superintendent of Contrabands in the city, worked concurrently with the military. Gladwin established the Contraband and Freedmen’s Cemetery to bury African Americans who died, largely from disease contracted in overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions.

Control between the military and Contraband Administration blurred with the arrival of the USCT. Quartermaster Lee set aside a plot in the Soldiers’ Cemetery for Black soldiers and some were buried there. Gladwin, however, felt that these dead were his responsibility and he proceeded to bury about 120 in his cemetery. The issue of where these men should be interred came to a head when hospitalized soldiers in the USCT made known that they would only escort their dead for burial in the military cemetery. The following day, Gladwin posted guards at the gates of the military cemetery, stopped a Black burial escort, arrested its hearse driver, and diverted the body to the Contraband and Freedmen’s Cemetery. That night, African American soldiers created their petition, which was forwarded to Colonel Lee. They presented their case in stirring language that still possesses the power to move:

We are not contrabands, but soldiers of the U.S. Army, we have cheerfully left the comforts of home, and entered into the field of conflict, fighting side by side with the white soldiers, to crush out this God insulting, Hell deserving rebellion. As American citizens, we have a right to fight for the protection of her flag, that right is granted, and we are now sharing equally the dangers and hardships in this mighty contest, and should share the same privileges and rights of burial in every way with our fellow soldiers who only differ from us in color.

The authority for resolving the dispute rested with Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs. Lee wrote to Meigs that “the feeling on the part of the colored soldiers is unanimous to be placed in the military cemetery and it seems but just and right that they should be.” Meigs wholeheartedly agreed. He ordered all Black soldiers to be buried in the military cemetery and had those already in the segregated cemetery reinterred so they could be laid to rest alongside their comrades in arms of either color. Gladwin was removed from his position two weeks later.

By Richard Hulver, Ph.D.

Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.

History of VA in 100 Objects

After World War I, claims for disability from discharged soldiers poured into the offices of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the federal agency responsible for evaluating them. By mid-1921, the bureau had awarded some amount of compensation to 337,000 Veterans. But another 258,000 had been denied benefits. Some of the men turned away were suffering from tuberculosis or neuropsychiatric disorders. These Veterans were often rebuffed not because bureau officials doubted the validity or seriousness of their ailments, but for a different reason: they could not prove their conditions were service connected.

Due to the delayed nature of the diseases, which could appear after service was completed, Massachusetts Senator David Walsh and VSOs pursued legislation to assist Veterans with their claims. Eventually this led to the first presumptive conditions for Veteran benefits.