National cemeteries originated out of necessity during the American Civil War. In the summer of 1862, as casualties mounted at an alarming rate, Congress empowered President Abraham Lincoln to purchase and enclose burial plots as national cemeteries to inter the growing number of Union dead. The National Cemetery Act of February 22, 1867, formalized details of the system and appropriated funds for temporary and then permanent features, including walls, grave markers, and “at the principal entrance of each of the national cemeteries…a suitable building to be occupied as a porters lodge.” The statute also funded the hiring of disabled Civil War Veterans as superintendents to live and work in the lodges.

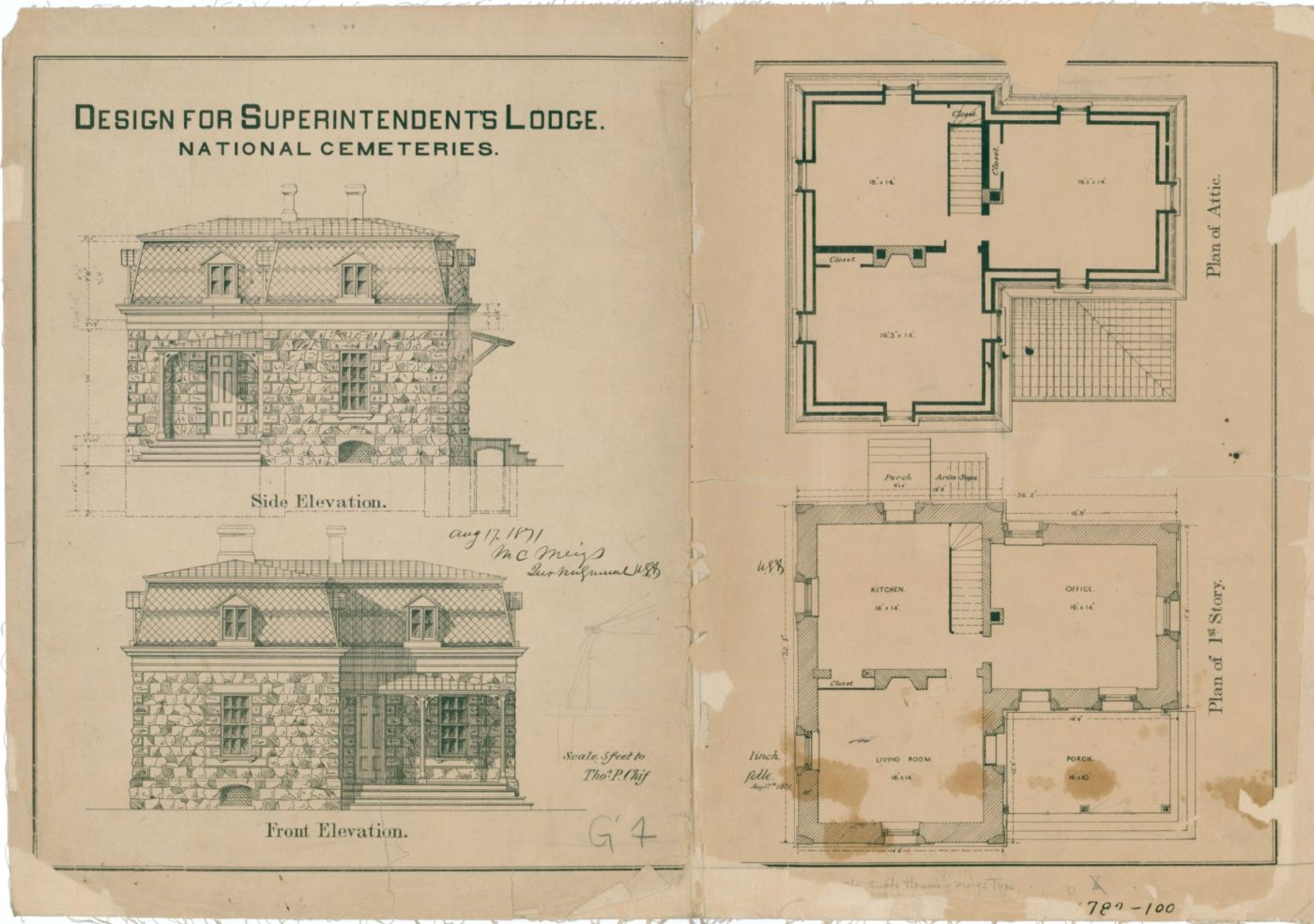

The first lodges—small, inadequate, wood frame structures—were temporary. In the 1870s, the U.S. Army’s Office of the Quartermaster General, which was responsible for the cemeteries, began to replace the original lodges with standardized permanent lodges built in the French Second Empire style, popular from 1852 to 1870. The design represented federal authority in the South where many national cemeteries were located. Brigadier General Montgomery C. Meigs, the Quartermaster General from 1861 to 1882 and a brilliant engineer, oversaw this program.

Edward Clark, who served under Meigs during the Civil War and afterwards became the Architect of the U.S. Capitol, designed them. Suggestions from superintendents led him to draft in 1869 a plan for an L-shaped building, one-and-a-half stories high, with six-rooms and a mansard roof. A prototype was erected in 1870 at the Richmond National Cemetery in Virginia. The layout was unique among Army construction at the time. The L-shape segregated the superintendent’s living quarters from his workspace, with separate entrances for each. The mansard roof also subverted strict Army regulations about space allowances for lower ranks by creating unaccounted-for living space above the first floor. Thomas P. Chiffelle, a surveyor, engineer, quartermaster clerk, and West Point classmate of Meigs, drew the definitive version of the lodge in August 1871.

Government contractors built fifty-five such lodges in brick or stone between 1871 and 1881. Since the Quartermaster General was the final approving authority, they were often described as “Meigs’ lodges” or were said to be constructed according to the “Meigs Plan.” In the early twentieth century, the lodges were deemed antiquated and some were replaced; after 1950, the government stopped building new lodges. Today, the National Cemetery Administration (NCA) has preserved eighteen French Second Empire lodges. Designated as historic resources, some are used as offices by NCA staff and other tenants. Despite being updated with plumbing, electricity and other modern touches, these iconic structures still serve as historical touchstones, reminding visitors of the post-Civil War origins of the national cemetery system.

Visit the National Cemetery Lodges: Documented for the Historic American Landscapes Survey website for more information.

By Richard Hulver, Ph.D.

Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.

History of VA in 100 Objects

After World War I, claims for disability from discharged soldiers poured into the offices of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the federal agency responsible for evaluating them. By mid-1921, the bureau had awarded some amount of compensation to 337,000 Veterans. But another 258,000 had been denied benefits. Some of the men turned away were suffering from tuberculosis or neuropsychiatric disorders. These Veterans were often rebuffed not because bureau officials doubted the validity or seriousness of their ailments, but for a different reason: they could not prove their conditions were service connected.

Due to the delayed nature of the diseases, which could appear after service was completed, Massachusetts Senator David Walsh and VSOs pursued legislation to assist Veterans with their claims. Eventually this led to the first presumptive conditions for Veteran benefits.