Flush with national pride after the War of 1812, U.S. lawmakers decided to show their gratitude to the redoubtable men who had won the first war against Great Britain. In 1818, Congress passed a law granting a lifetime pension to anyone who served for at least nine months in the Continental Army, Navy, or Marines during the American Revolution, provided the individual was “in need of assistance from his country for support.” Overwhelmed by the number of applications for pensions, Congress in 1820 revised the law to require claimants to supply proof of their financial distress.

Even under these more stringent terms, more than 15,000 Revolutionary War Veterans qualified for a pension. Joseph Winter was one of the unlucky few who did not. The German-born Winter lived in a settlement among his fellow immigrants near Bethlehem, Pennsylvania before the war, where he supported himself and his family as a weaver. His wife and children died sometime after the Revolution. As he grew older, his vision deteriorated and he could no longer perform the work required by his chosen trade. With no family to turn to, no means of earning a livelihood, and no pension, Winter became homeless.

On a snowy night in December 1829, portrait painter John Neagle encountered Winter on the streets of Philadelphia. The sight of the destitute Revolutionary War Veteran saddened and dismayed Neagle. Despite communication difficulties, as Winter’s first language was German, Neagle invited him home to hear his story.

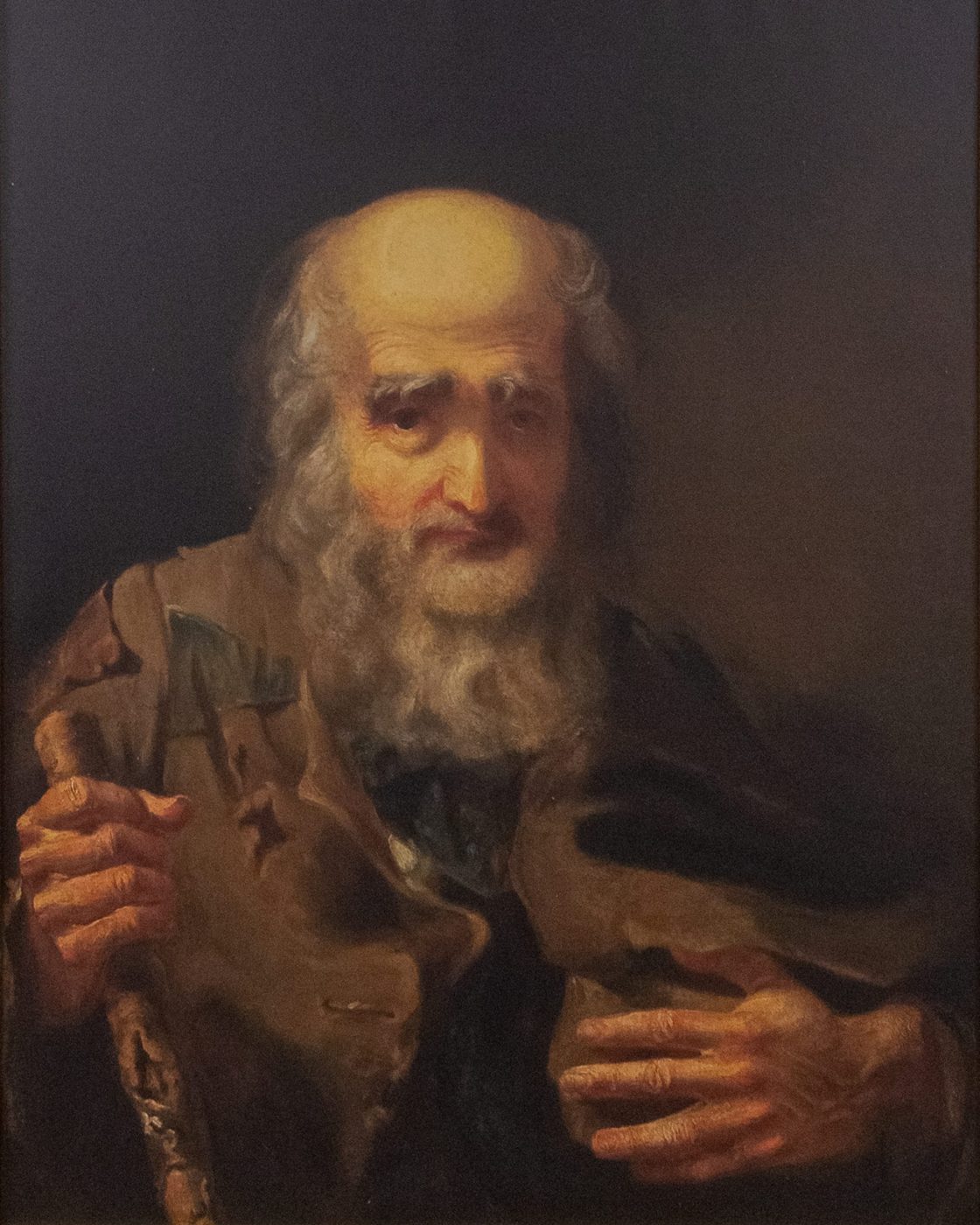

Neagle used his local grocer as a translator. After learning the details of Winter’s life and his services in the Revolution, Neagle decided to paint his portrait. While many artists had produced portraits of Revolutionary War veterans, the subjects were all shown in the prime of their lives. Neagle chose to represent Winter as he was in 1829, old, downtrodden, wearing threadbare clothes, his face lined with the hardships he had experienced. At the same time, Neagle was careful to portray Winter with dignity, in a manner calculated to invite sympathy for his situation and his suffering.

The completed portrait attracted a great deal of attention. Another artist, John Sartain, created an engraving of the picture that was sold under the title Patriotism and Age. Through the portrait and the engraving, Winter became the symbol for thousands of elderly veterans. The popularity of the engraving drew the government’s attention to the plight of these men who earlier in their lives had fought for the nation’s independence. In 1832, Congress passed a comprehensive pension act, which offered a monthly payment to almost all surviving Veterans of the conflict, the members of the state militias included and without regard to finances or disabilities. Four years later, Congress extended the same benefits to widows of Revolutionary War Veterans.

What became of Winter after his meeting with Neagle is unknown. However, his image, captured in the portrait and engraving, serves as a powerful reminder that the problem of Veteran homelessness is as old as the nation itself.

By Olivia Holly-Johnson

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.