In early 2019, the VA Medical Center (VAMC) in Seattle, Washington, made a breakthrough. A pending surgical procedure called for the removal of a tumor from a Veteran’s kidney, complicated by a unique congenital configuration of the veins and arteries. The surgical team needed to assess the best approach to minimize the risk of catastrophic blood loss while removing the tumor.

The solution to this complex medical problem was not an implant, device, or medication, but an innovative pre-surgical collaboration and 3D printing technology. Working together for the first time, the surgical and medical imagery teams and the 3D printing specialist produced an exact model of the patient’s kidney. In a 2019 article, Dr. Beth A. Ripley, a VA radiologist and Deputy Chief Officer of Diagnostic Imaging Services at the Seattle VAMC, described how the process worked:

First, a physician uses software to trace out the important anatomy on each image slice. Next, those traces are stitched together into a digital three-dimensional blueprint of the anatomy. Finally, this digital 3D blueprint is sent to a 3D printer, where the anatomy is physically reconstructed to scale. The end result is a near-perfect replica of the patient’s anatomy which the surgeon or patient can hold in their hands and inspect from all angles.

The medical staff used the finished product both to explain the procedure to the patient and as a planning tool for themselves. The ability to examine the 3D model prior to surgery saved time and operating costs, reduced risk for the patient, and, ultimately, led to a successful outcome. The tumor was removed and the patient made a full recovery.

VHA’s integrated 3D printing network has steadily expanded since it was launched at VA’s Puget Sound Healthcare System in January 2017. By 2020, the number of VHA medical facilities that possessed 3D printing capabilities had grown to thirty. The printing of 3D models has also branched out beyond kidneys and been applied to treat many different conditions. In one case, a model created to plan hip surgery for an amputee showed it would too risky and the operation was cancelled. The technology has been used for non-surgical purposes as well, such as printing customized hand braces that allow an exact match when replacing an existing worn brace.

While 3D printed items may not fit the textbook definition of historical artifacts, the 3D tumor contributes to our understanding of the history of medical innovation in VA. The contemporary nature of the object also highlights the importance of preserving certain seminal artifacts in “real time” before they would otherwise be lost, discarded, or tucked away in a closet as curiosities.

Working with VHA officials, the VA History Office obtained the 3D tumor in September 2021 and brought it to the National VA History Center’s temporary storage site in Dayton, Ohio, for safekeeping. The 3D tumor joins the growing collection of medical devices developed by VA researchers that have benefited Veterans and improved patient care and treatment worldwide.

By Michael Visconage

Chief Historian, Department of Veterans Affairs

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 93: Occupational Therapy Floor Loom

During World War I and afterwards, the United States committed to rehabilitating sick and wounded soldiers so they could resume productive lives in the civilian workforce. The emerging field of occupational therapy played a crucial role in the rehabilitative process.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 92: Pension Attorney Promotional Pamphlet

The expansion of the Civil War pension system was a cash windfall for pension attorneys. These lawyers used their legal know-how to help Veterans obtain benefits, but they were also accused of exploiting their clients and fleecing the government.

History of VA in 100 Objects

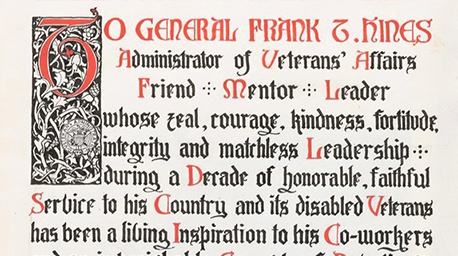

Object 91: Hines Scrapbook Dedication

In 1933, VA staff presented agency chief Frank Hines with a scrapbook commemorating his ten years of service to Veterans. Intended as a personal keepsake for Hines, the scrapbook also offers a snapshot of a particular time in VA history.