In May 2009, twelve VA doctors and scientists gathered in a small conference room in Rockville, Maryland, to brainstorm about the design of VA’s first-ever large-scale genetic research program. They wanted to collect medical information from Veterans along with blood samples to extract DNA, with the goal of creating a genomic biobank or database for researchers to explore how genes affect health and disease. The groundwork for such a program had already been put in place by Joel Kupersmith, VA’s Chief Research and Development Officer. Dr. Kupersmith championed the initiative in early discussions with VA Secretary R. James Nicholson and commissioned a series of independent focus groups and a follow-up survey of Veterans to assess their attitudes around the new field of genetic research.

Dr. Kupersmith and other VA officials were highly encouraged by the results of the survey, which were published in the journal Genetics in Medicine the month of the meeting in Rockville. An overwhelming 83 percent of Veterans who completed the online survey supported the creation of a database for genetic research at VA, with 71 percent saying they would participate in the program themselves. Still, that left open the question of how many Veterans should be enrolled. The database needed to be large for research studies to yield statistically significant results on a wide range of health conditions. Timothy O’Leary, the Director of VA’s Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service, challenged the group to think big. They started with 100K and continued throwing out even larger numbers before settling on one million Veteran participants. Over dinner, they also came up with a name: the Million Veteran Program.

For VA to undertake a research program of this magnitude was more than ambitious; it was also unprecedented. At the time, the largest research initiative VA ever conducted was a colonoscopy study with 10,000 participants. To date, most genetic research studies involved a few thousand people at best.

Yet, several factors made VA ideally suited to execute a program on this scale. The agency oversees the largest health care system in the United States. With nine million Veterans enrolled in VA health care, VA has access to an enormous patient population, many of whom want to give back and help their fellow Veterans. For the past 30 years or more, VA has also employed a sophisticated electronic health record system to track Veteran treatment and medical information.VA also has a well-developed research infrastructure and supports research efforts at more than 100 VA medical centers and other facilities nationwide.

Over the next two years, under the leadership of Dr. Kupersmith, a dedicated team in the Office of Research of Development and the field shepherded MVP through the planning and development stages, pitching the program to Congress and other stakeholders, lining up VA medical centers as enrollment sites, and writing the research protocol. This last task proved complicated, as enrollees would be agreeing to share genetic and health data not just for one specific research project but for any number of approved studies in the future. This, too, had never been done before at VA. The MVP team cleared this important hurdle when VA’s Central Institutional Review Board approved the protocol in 2010.

Enrollment in MVP began in early 2011 at nine different sites. Recruitment efforts ramped up from there. Over the next five years, MVP opened 52 main enrollment sites plus more than 65 satellite locations across 37 states. The program also launched an enormous and still ongoing mail campaign to solicit participation, sending out letters and questionnaires to millions of Veterans. By March 2014, a quarter million Veterans had joined the program. MVP reached the half-million mark on August 1, 2016. The COVID-19 pandemic slowed its march to one million participants, but the program is closing in on that milestone, with nearly 900,000 Veterans enrolled as of June 2022.

Even in the program’s early stages, VA investigators took advantage of the genetic and health data collected from participants to initiate studies on a range of pressing health problems afflicting Veterans. The first studies using the MVP database focused on such conditions as heart and kidney disease, post-traumatic stress disorder, Gulf War Illness, and substance use. Since 2015, as more research projects have gotten underway, the scope of inquiry broadened to include diabetes, prostate and breast cancer, and anxiety and depression, to name just a few of the many health conditions MVP researchers are studying.

The program has also been enlisted in the fight against COVID-19. One VA study, the results of which were published in April 2022, established a link between genetic variants associated with severe COVID-19 and other medical conditions that place individuals at high risk if they contract the virus. Another study found that Black Veterans who carry a genetic variation linked to kidney disease were more than twice as likely to die from COVID-19, which triggered severe kidney infection in many of these patients. This discovery was made possible thanks to the diversity of Veterans in MVP, which has more people of African descent than any other research program in the world.

Other MVP studies promise to yield equally important insights into how genes interact with lifestyle issues and environmental factors to impact health. Over time, the knowledge gained through these studies will lead to groundbreaking improvements in the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of illness and disease for Veterans and all people.

Learn more about VA’s Million Veteran Program and its research projects.

*This entry has been revised to include additional detail about the contributions of Dr. Joel Kupersmith to MVP.

By Claudia Gutierrez, Public Relations Specialist, Million Veteran Program, and Jeffrey Seiken, Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

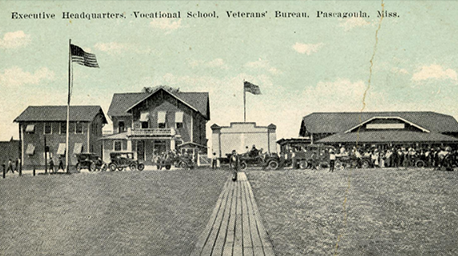

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.