VA national cemeteries contain numerous memorials honoring the service members who became prisoners of war (POW) or went missing in action (MIA) from the Revolutionary War to the present. While all pay powerful tribute to the sacrifices and suffering of POWs and MIAs, the memorial at Riverside National Cemetery in southern California is notable for an additional reason. In 2004, while it was still under construction, Congress designated it the “Prisoner of War/Missing in Action National Memorial.”

Since opening in 1978, Riverside has become the nation’s largest national cemetery as well as one of the busiest, averaging more than 8,000 burials a year. Over 290,000 grave sites are spread across 1,236 acres. The POW/MIA memorial stands east of the main gate. The dramatic bronze sculpture created by Vietnam Veteran Lewis Lee Millett, Jr., forms the centerpiece of the memorial plaza. The statue depicts an American serviceman, exhausted, kneeling in agony, bound by captors with arms pinned behind his back by a bamboo rod, looking upward. Millett based the sculpture on U.S. Air Force Captain Lance Sijan, who ejected from his damaged aircraft over Laos in November 1967 and evaded capture for more than a month before he was finally taken prisoner. After being tortured and enduring severe privation, he died in captivity on January 22, 1968. President Gerald Ford presented Sijan’s parents with a posthumous Medal of Honor in 1976.

Millett himself served in Vietnam in 1972 and afterwards was assigned to the 101st Airborne from 1974 to 1977. His father was the much-decorated Veteran of three wars, Colonel Lewis Lee Millett, Sr.* As an Army captain in the Korean War, the elder Millett received the Medal of Honor for his heroic conduct leading a bayonet charge against a hilltop position. POWs were an important issue to the Millett family. Millett, Jr., donated his $80,000 artist’s commission for the sculpture to the memorial and pledged to do the same with all proceeds from the sale of replicas of the statue. Funding for the monument, which cost around $675,000, came entirely from private donations.

Millett said that he wanted his work to convey the message that “No American is expendable. No American should be left behind. That should be a national as well as military motto.” A semi-circle of nine vertical black marble slabs around the central figure provides a sense of imprisonment. An inscription on one of the end slabs captures the meaning and spirit of the memorial:

We honor here the sacrifice of hundreds of thousands of Americans held Prisoner of War, and those still listed as Missing in Action since the time of the American Revolution. Some died from disease and starvation, some perished in death marches, some were tortured, and some were lost, gone forever from their families…All were deprived of their liberties so that you may enjoy yours.

Riverside National Cemetery is also home to the Medal of Honor memorial, dedicated in 1999, and the Fallen Soldier/Veterans’ Memorial, completed a year later. Dedication of the POW/MIA memorial occurred, fittingly enough, on September 16, 2005, the date earmarked by presidential proclamation as National POW/MIA Recognition Day.

Visit our virtual exhibit, “Prisoners of War – Honoring those in National Cemeteries,” to learn more about heroic survival stories of POWs.

*Lewis Lee Millett, Sr. died November 14, 2009, and is buried in Riverside National Cemetery (Sec. 2, Site 1910).

By Richard Hulver, Ph.D., Historian, National Cemetery Administration, and Nalia Warmack, Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

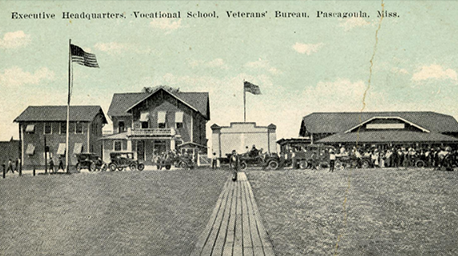

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.