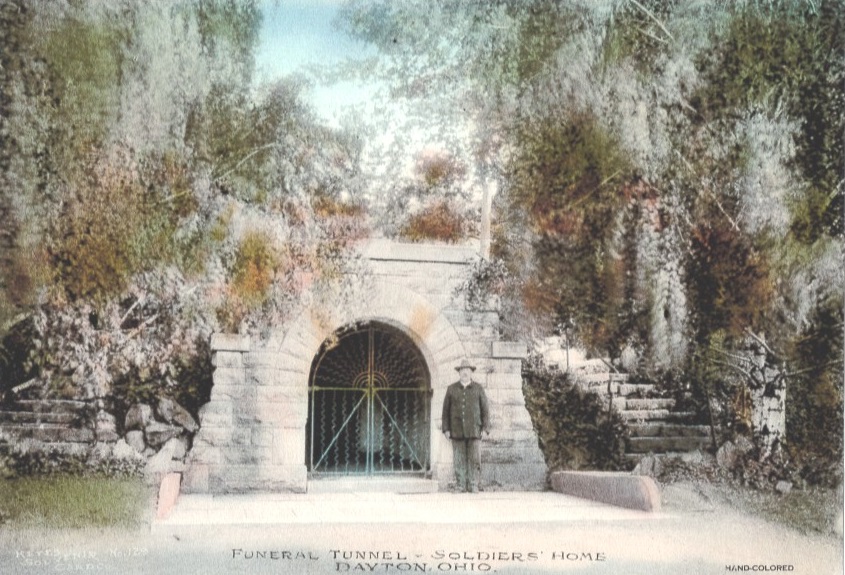

The Civil War Veterans who resided in the barracks or entered the hospital at the Central Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (NHDVS) in Dayton, Ohio, knew that the home cemetery was most likely going to be their final resting place. Then as now, burial was among the government benefits provided to those who served honorably. At the Dayton campus, home to more than 5,000 ”inmates” at the turn of the twentieth century, a Veteran’s last journey, reported the Cincinnati Enquirer, followed a literal “underground path of death.” Dayton’s Tunnel terminated at a gated portal on the edge of what is now Dayton National Cemetery.

This subterranean route, 300 feet long from hospital to cemetery, is a remnant of the late nineteenth-century network of tunnels excavated to hold pipes that moved steam heat, sewage, and utilities throughout the campus. It began below the chief surgeon’s headquarters in the Victorian three-story, 300-bed hospital at a “dead-room”—an underground apartment containing the morgue and storage for a supply of new coffins. Lights illuminated the tunnel, 8 feet across and 7 feet tall. It was improved in 1887 with a new receiving vault hailed as a “very great convenience to the institution.”

The Cincinnati Enquirer story about life at the home, published in 1891, describes the Veteran’s last journey and final honors. From the dead-room, “the casket containing the remains of the old hero is placed on a small, flat car” that transports it through the tunnel to the opening at the edge of the cemetery:

[At the entrance,] a guard in waiting unlocks the heavy iron gates, which swing open and the casket is received by the funeral corps and placed in the hearse in waiting. A line of forty or more soldiers has already been formed. The casket is borne to the church where the funeral services are held. Then the procession forms in line and the cemetery is reached in a short time. The body is interred and a salute is fired, and all is over.

One Veteran reflected, “Our little cemetery over yonder is growing larger and larger. Not a day passes that does not see one or more of us go through the tunnel.” He was right. Between 1890 and 1900, an average of 383 residents of the Central Branch died annually.

After the original hospital was demolished in the 1940s, the brick-lined passage was sealed off at both ends. To passersby, the opening in the cemetery remains the only visible evidence of the tunnel. Its current appearance contrasts starkly with its historic countenance, which is best preserved in picture postcards. The once-elegant portal is barely recognizable: the entrance is sealed up, the dressed stonework and metal gates are gone, and the stone steps descending into the cemetery on each side of the former opening are encroached by the steep grassy slope. The tunnel opening, like so many other long-lost features of the historic Central Branch, attracted thousands of visitors in its heyday. In an incongruous juxtaposition, the image was even printed on souvenir ceramic soap dishes sold at the home’s newsstand along with postcards.

The funeral tunnel at Dayton is a unique VA historic resource that has been documented and evaluated by engineers and historic preservationists using non-invasive ground-penetrating radar, digital photogrammetry, and low-light photography, among other techniques. Stakeholders at VA and non-profit partners are optimistic that the portal in the cemetery may be restored to its original appearance along with a representative portion of the tunnel to interpret the history of the Veteran’s last journey. The Dayton NHDVS campus, including the cemetery, was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 2012.

By Sara Amy Leach

Senior Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.

History of VA in 100 Objects

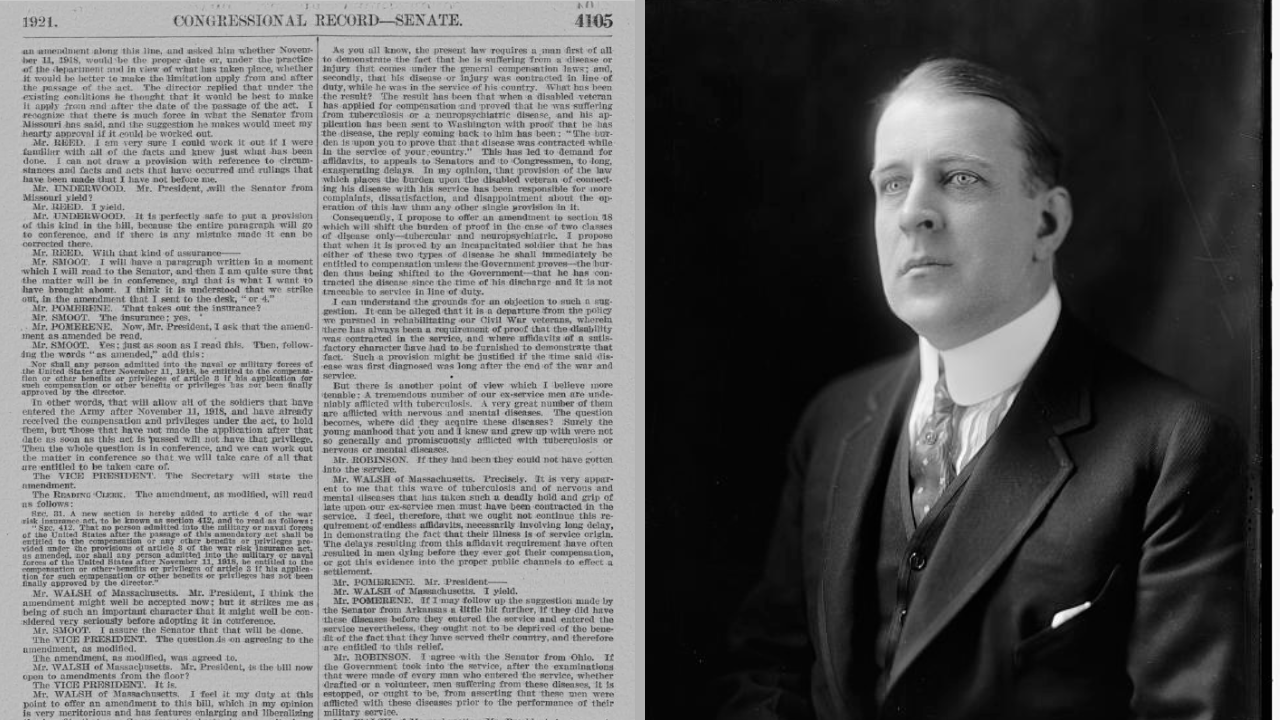

After World War I, claims for disability from discharged soldiers poured into the offices of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the federal agency responsible for evaluating them. By mid-1921, the bureau had awarded some amount of compensation to 337,000 Veterans. But another 258,000 had been denied benefits. Some of the men turned away were suffering from tuberculosis or neuropsychiatric disorders. These Veterans were often rebuffed not because bureau officials doubted the validity or seriousness of their ailments, but for a different reason: they could not prove their conditions were service connected.

Due to the delayed nature of the diseases, which could appear after service was completed, Massachusetts Senator David Walsh and VSOs pursued legislation to assist Veterans with their claims. Eventually this led to the first presumptive conditions for Veteran benefits.