The Don Ce-Sar Hotel has graced the Gulf of Mexico beachfront in St. Petersburg, Florida, for almost a century. Known as the Pink Palace for its rosy hue and castle-like appearance, the property was a playground for the rich and famous during its heyday in the 1930s. Added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975, the Spanish Mission-style resort remains a popular destination for vacationers today. But the Don Ce-Sar’s storied history also includes a lesser-known period when it catered to a very different clientele. During World War II, the government converted the hotel into a military hospital and then a convalescent center for airmen. Immediately after the war, the building became the site of the largest Veterans Administration regional office in the state. Over the next twenty years, in halls repainted a shade of government green, VA employees attended to thousands of Veterans seeking their GI Bill and other government benefits.

A visionary Irish immigrant, Thomas Rowe, built the Don Ce-Sar. He originally planned a six-story structure with 110 guestrooms but then decided to double that number by adding three more stories, bringing the total cost to over $1 million. The Don Ce-Sar opened in January 1928. Less than two years later, the Great Depression struck, but Rowe weathered the hard times. Business tycoons, entertainers, and the New York Yankees rented out blocks of rooms for the December-to-April season. Rowe died in 1940 and business declined after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941. With the future of the hotel uncertain, the government stepped in. Florida Senator Claude Pepper arranged for the Don Ce-Sar to be condemned, enabling the Army to purchase the property from Rowe’s widow for only $440,000. The government spent another $200,000 to remodel the interior into a hospital for the large population of soldiers stationed at area military bases. The Army installed laboratories, clinics, and offices on the ground floor, demolished walls separating guestrooms to create patient wards, and set up operating rooms on the eighth floor.

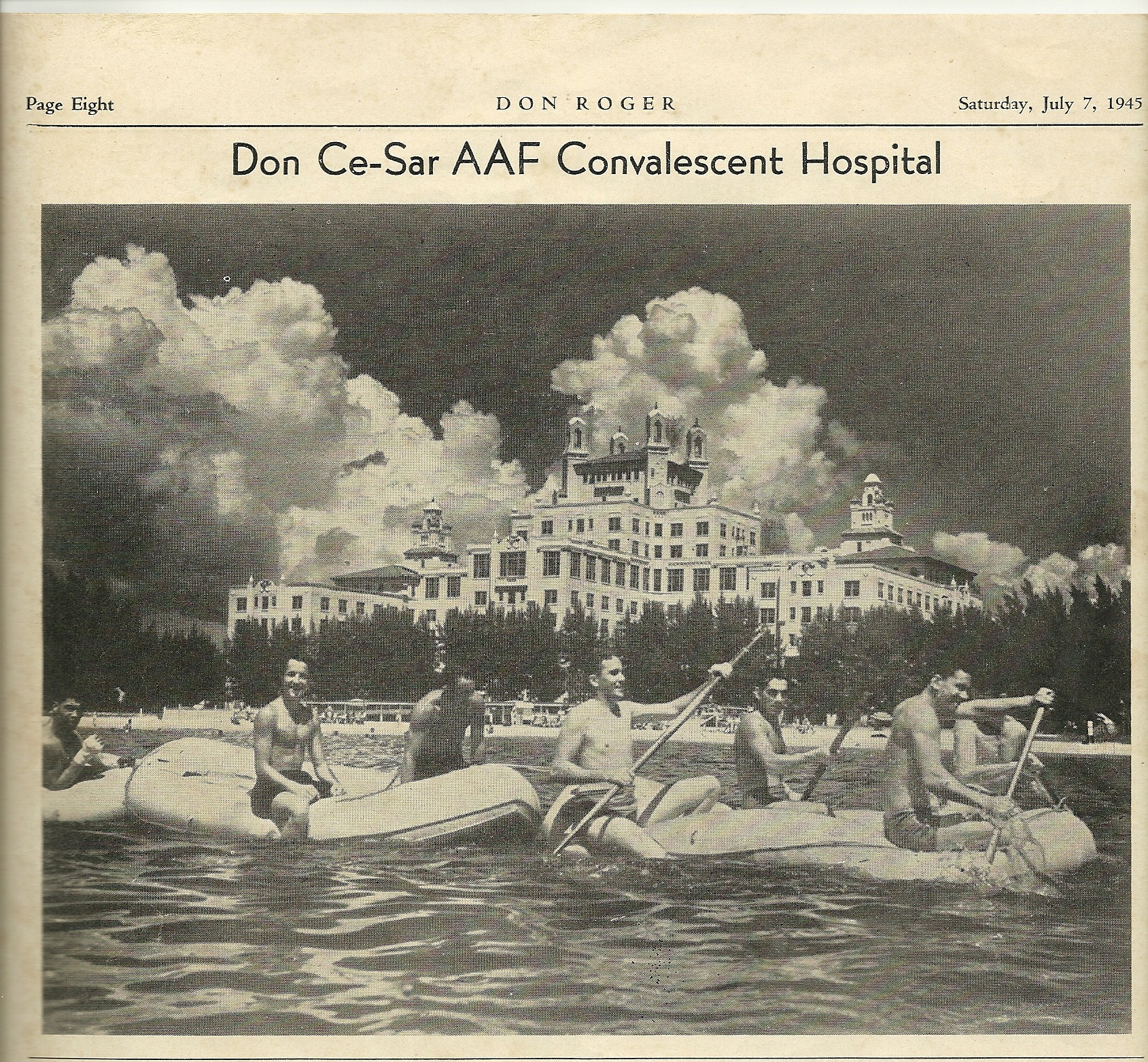

In early 1944, military authorities decided to repurpose the Don Ce-Sar more in line with its origins as a posh resort on Pass-a-Grille Beach. The Army Air Forces took over the hospital as a convalescent center for air crews suffering from combat fatigue. Patients basked in the sunshine, swam in the warm waters, went boating, and enjoyed other beach amenities. They also received psychiatric counseling. After six to eight weeks, doctors assessed their cases. Recovered airmen returned to their overseas units. The rest were assigned non-combatant duties or discharged from the service.

The Army vacated the facility after the war, but the government did not relinquish the Don Ce-Sar. The interior underwent a second remodel, this time to house the Veterans Administration regional office that had outgrown its downtown St. Petersburg building. As incongruous as it seems to put a federal office in a former beachfront hotel, VA needed space to process the surge in applications, claims, and correspondence generated by the GI Bill and the military’s demobilization. And the Don Ce-Sar had ample space to accommodate the 1,400 employees who staffed the office and the hundreds of steel file cabinets packed with Veterans’ records. The cabinets filled the grand ballroom and the regional office director took up residence in the penthouse apartment once occupied by hotel builder Rowe.

VA expected the arrangement at the Don Ce-Sar to be temporary. It planned to open regional offices in the state’s other two population centers, Miami and Jacksonville. Once those were established, the Don Ce-Sar would be downgraded to a sub-regional office with a smaller staff. The Miami office opened in May 1946 to provide services to Veterans in Florida’s ten southernmost counties. Not long after, VA decided against making changes to the Don Ce-Sar’s status. The Miami regional office lasted less than ten years. In 1955, VA calculated it could save $215,000 annually by consolidating benefits operations for the state in one location. Accordingly, in September, a convoy of moving vans transported more than 100 tons of records and 30 tons of office equipment from Miami to St. Petersburg.

In 1961, the concrete building showed evidence of deterioration and the government had to spend $235,000 to fix the roof and make other repairs. A subsequent evaluation concluded that the costs of updating the aging hotel would be prohibitive. In 1967, the VA regional office ended its stay at the Don Ce-Sar and moved into new offices in downtown St. Petersburg. In the early 1970s, the now vacant Don Ce-Sar appeared headed for the wrecking ball until a local developer bought it for $400,000—slightly less than what the government paid in 1941. Extensive renovations restored the hotel to its former splendor. With its grand reopening in November 1973, the Don Ce-Sar resumed its place as the Pink Palace overlooking the emerald-green waters of Florida’s Gulf Coast.

H/T to Jessica Carriveau, an Information System Security Manager who works out of the St. Petersburg Regional Office, now co-located with the VA Medical Center in Bay Pines, for suggesting this topic.

By Maureen Thompson, Ph.D.

Historian, Central Alabama VA Medical Center-Tuskegee

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

American prisoners of war from World War II, Korea, and Vietnam faced starvation, torture, forced labor, and other abuses at the hands of their captors. For those that returned home, their experiences in captivity often had long-lasting impacts on their physical and mental health. Over the decades, the U.S. government sought to address their specific needs through legislation conferring special benefits on former prisoners of war.

In 1978, five years after the United States withdrew the last of its combat troops from South Vietnam, Congress mandated VA carry out a thorough study of the disability and medical needs of former prisoners of war. In consultation with the Secretary of Defense, VA completed the study in 14 months and published its findings in early 1980. Like previous investigations in the 1950s, the study confirmed that former prisoners of war had higher rates of service-connected disabilities.

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.