In June 1941, Charles Ray Smith—aviation mechanic, Army Veteran, and past commander of the American Legion post in Gridley, California—died suddenly after a surgical procedure at age 52. His brothers and young son had the body cremated at the new crematorium at what is now Los Angeles National Cemetery. Afterward, his ashes were placed in the nearby indoor columbarium, Bay 300, Row A, “Cinerarium” 1—the first interment. Cremation was a practical choice for Smith’s family and their decision reflected the move away from casket burials on the West Coast at this time.

In the United States, cremation of the dead and interment of the ashes or cremains in above-ground structures known as columbaria grew increasingly popular in the 1920s. Before contagious disease was fully understood, cremation was touted as a sanitary way to dispose of bodies—and perhaps a necessity in a pandemic. By the time scientific advances in the 1930s disproved this idea, many Americans viewed cremation as an appealing burial option. This was particularly true in California, where one-third of all U.S. crematories were in operation. Environmentally practical and architecturally stylish columbaria became a common asset in the state’s cemeteries.

At the Los Angeles Veterans cemetery, which opened in 1889 on the grounds of the Pacific Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, the graves of Veterans who served from the Civil War through World War I filled much of the acreage. With space at a premium and cremations on the rise, VA built an indoor columbarium and chapel-crematorium in 1940-1941. The Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal-era agency that carried out public works projects, provided the money and the manpower for their construction. The WPA completed other improvement projects at the cemetery, landscaping the grounds, resetting headstones, and building a rostrum.

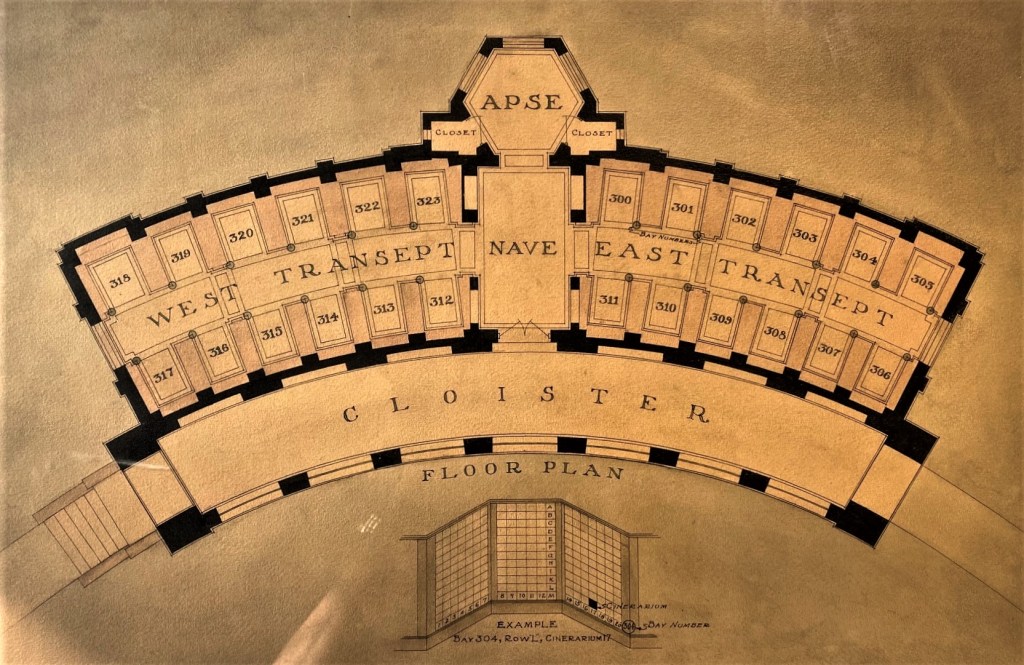

The arc-shaped columbarium, with a covered arcade or “cloister” on the front, was strategically placed midway down the cemetery’s greensward as a backdrop to the low brick rostrum. Inspired by California’s historic eighteenth-century Catholic missions, the structure incorporated “second-hand brick” with “squeezed joints,” terra cotta roof tiles, and stucco. The use of clear, insulating hollow glass block in the windows added a forward-looking material. First introduced to consumers in 1933 at the Chicago Century of Progress Exhibition, glass block gained favor through the decade.

Inside the columbarium, a central vestibule connects two wings lined with two-dozen bays. Each bay has three walls filled with niches, twelve rows from floor to ceiling that are unmistakably reminiscent of post office boxes. The niche covers are made of an early metal alloy. Skylights and clerestory windows draw in natural light to create a pleasant setting “to visit the dead,” a stark distinction from previous generations of dark, somber columbaria. The plans for the Los Angeles columbarium included a matching structure to the east, which would have created a symmetrical focal point in the cemetery, but the second structure was never realized.

The nondenominational chapel erected by the WPA at the cemetery’s entrance provided related functions such as viewing rooms and the crematorium. The small number of chapels proposed or built at national cemeteries after World War II were short-lived. By the late 1970s, the Los Angeles chapel was used for administrative and committal-service functions, and the crematorium equipment had been removed.

Decades after Private Smith was inurned at Los Angeles and shortly after VA assumed responsibility for the national cemetery system in 1974, the agency made outdoor columbaria a requirement at all new cemeteries. The first was completed at Riverside National Cemetery in California. By the early 1980s, they were also being built at existing cemeteries in locations unsuitable for caskets, such as hillsides and along perimeter walls. VA cremation burials had reached 9 percent, and the addition of columbaria enabled older closed cemeteries to reopen.

The future of Los Angeles National Cemetery, where available gravesites were generally depleted by 1976, has been revived with an all-columbaria tract opened in 2019 that eventually will accommodate 90,000 cremains. The need for such facilities is greater than ever, as cremation interments accounted for over 55 percent of all VA burials in 2021, just under the national rate. Meanwhile, VA is investing in its historic columbarium with a comprehensive rehabilitation project that will include a new tile roof, repairs to structural components and windows, and interior finishes. This unique building illuminates the shift in burial practices that occurred between the world wars and, like so many trends, it started in California.

By Sara Amy Leach

Senior Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

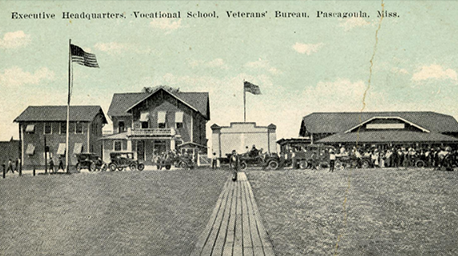

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.