A conversation about oranges inspired the invention of the medical imaging technique known as computed tomography or CT scan by William H. Oldendorf, a neurologist at UCLA and the Los Angeles VA Hospital. While attending a social event in the late 1950s, Oldendorf listened as an engineer described his efforts to use x-rays to identify oranges whose interiors had become dehydrated due to frostbite. Oldendorf was struck by the parallel between an orange and a patient’s head and wondered if a revolving beam of x-rays could be employed in a similar manner to create a detailed picture of the brain’s internal structure. Oldendorf had been looking for a more direct way of imaging the brain, sparing patients from existing procedures that were painful, invasive, and even a little dangerous. “Each time I perform one of these primitive procedures I wonder why no more pressing need is felt by the clinical neurological world to seek some technique that would yield direct information about the brain without traumatizing it,” he wrote in a 1961 paper.

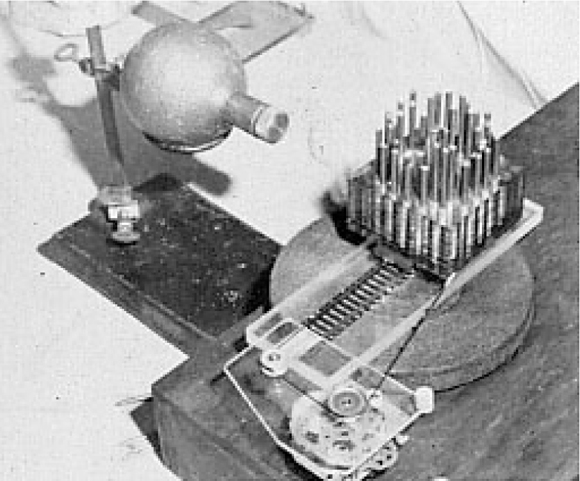

A second conversation propelled him further along the path of his groundbreaking work on neuroimaging. The VA hospital’s acting research chief asked Oldendorf if he would be interested in researching the topic and offered him $3,000 on the spot. With this funding in hand, he set out to develop a prototype scanner. He built the device in his garage using household items, including a frying pan and parts scrounged from his son’s model train set. For simplicity, he kept the x-ray source and the detector directly across from it stationary. Instead, it was the head, represented by iron and aluminum nails of varying size mounted on a record turntable, that rotated. In his patent application, however, Oldendorf also included several sketches in which the object under examination remains fixed while the x-ray apparatus rotates or moves around it in some fashion. He filed the patent in 1960. A year later, he published what would prove to be his seminal paper describing his experimental model and the concept of radiographic tomography. In 1963, the U.S. Patent Office approved his patent for a “Radiant Energy Apparatus for Investigating Selected Areas of the Interior.”

In the introductory section of the patent, Oldendorf stated that one of the goals “of the present invention [is] to provide such a system which is mechanically simple and inexpensive both to operate and to manufacture.” He ran into trouble persuading investors on these last points. X-ray manufacturers dismissed the device as too expensive to produce and they also questioned its usefulness. One company rejected his overture with a letter that concluded, “Even if it could be made to work as you suggest, we cannot imagine a significant market for such an expensive apparatus which would do nothing but make a radiographic cross-section of a head.” This assessment could not have been more shortsighted.

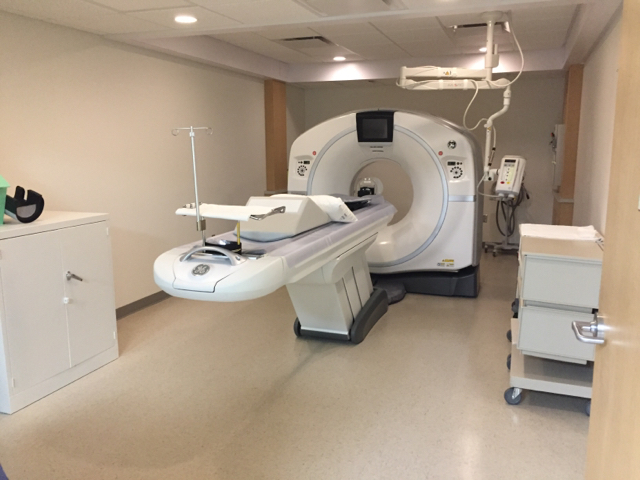

After failing to find a backer for his invention, Oldendorf turned his attention to other projects. In 1972, a commercial version of the CT scanner did finally reach the market, but it was based on a design developed and patented by Godfrey N. Hounsfield, an engineer and researcher at Electric and Musical Industries or EMI—the same company that released the Beatles’ records in the 1960s. Within a few years, multiple companies were producing new and improved versions of the scanner and its value as a diagnostic tool for doctors was indisputable. Hounsfield went on to win the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1979 with physicist Allan M. Cormack for their contributions to the “development of computer assisted tomography.” VA researcher Dr. Rosalyn Yalow, who was herself a Nobel laurate, also put forth Oldendorf’s name for the prize, but the Nobel Assembly made an eleventh-hour decision to exclude him from the award. His supporters attributed the snub to the committee’s tendency to favor research scientists over clinical physicians like Oldendorf. Legal considerations may have also played a role, as EMI was tied up in ligation with rival manufacturers over infringement of its patent rights on the CT scanner.

Although denied a Nobel Prize, Oldendorf received many other prestigious honors for his work. Notably, in 1975, Oldendorf and Hounsfield were named co-recipients of the Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award “For discoveries that led to a revolution in diagnostic radiology, enabling scanning by computer-assisted tomography (CAT).” The award citation hailed the CT scanner “as one of the most important contributions in this field since the discovery of the X-ray in 1895.” VA doctors who daily rely on CT scans to detect and treat traumatic brain injuries, tumors, and other internal conditions would certainly agree.

Katie Rories, Historian, Veterans Health Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.