In August 1945, the United States detonated atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending World War II and ushering in the dawn of the Atomic Age. Two years later, the Veterans Administration started harnessing this technology for a very different purpose—to conduct medical research. VA’s use of nuclear energy to diagnose and treat disease expanded in the 1950s, culminating at the end of the decade in the installation of a small nuclear reactor beneath the VA hospital in Omaha, Nebraska.

The father of VA’s nuclear program was Dr. George M. Lyon, a Navy Veteran and member of the Manhattan project who joined VA in 1947 as Special Assistant for Atomic Medicine. His position had been established to help VA prepare for the evaluation of claims from Veterans exposed to atomic radiation. The year of his hiring, however, the Atomic Energy Commission began making radioisotopes available to medical investigators for clinical research under a strict licensing arrangement.

Produced in a nuclear reactor, radioisotopes are unstable forms of chemical elements that emit radiation as they decay. They proved of tremendous value to researchers because their properties made it possible to study different physiological processes with great precision. To coordinate the use of this material in its hospitals, VA created a Radioisotope Section and appointed Dr. Lyon its first chief.

By mid-1948, radioisotope labs were up and running at eight VA hospitals. That same year, Lyon recruited Dr. A. Graham Moseley, Jr., a chemistry professor at Marshall College in West Virginia, to be his deputy. Like Lyon, Moseley had held a war-time commission in the Navy and both men assisted with the nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific in 1946.

Dr. Moseley deserves much of the credit for the growth of VA’s nuclear medicine program. When Lyon was promoted in 1952, Moseley took over as head of Radioisotope Research and he continued to run the section until his retirement in 1966. During the 1950s, the number of VA hospital labs equipped to conduct medical research using radioisotopes grew to sixty. A survey of VA medical investigations at the end of the decade reported that more than 600 radioisotope projects had been approved. Researchers employed radioisotope tracer techniques to study such processes as coronary blood flow, fat digestion and absorption, and the rate of cholesterol synthesis within an autopsied human aorta.

As the field matured, VA physicians increasingly employed radioisotopes for clinical purposes, too. For instance, radioisotopes were used to evaluate liver and kidney function, determine the location of brain tumors, and treat hyperthyroidism. In 1966, the year of Dr. Moseley’s retirement, more than 60,000 VA patients benefited from radioisotope diagnostic procedures while another 600 received therapeutic doses of radioisotopes. That same year, VA established a Nuclear Medicine Service in the Department of Medicine and Surgery to coordinate the clinical application of radioisotopes across 88 nuclear medicine clinics and hospitals.

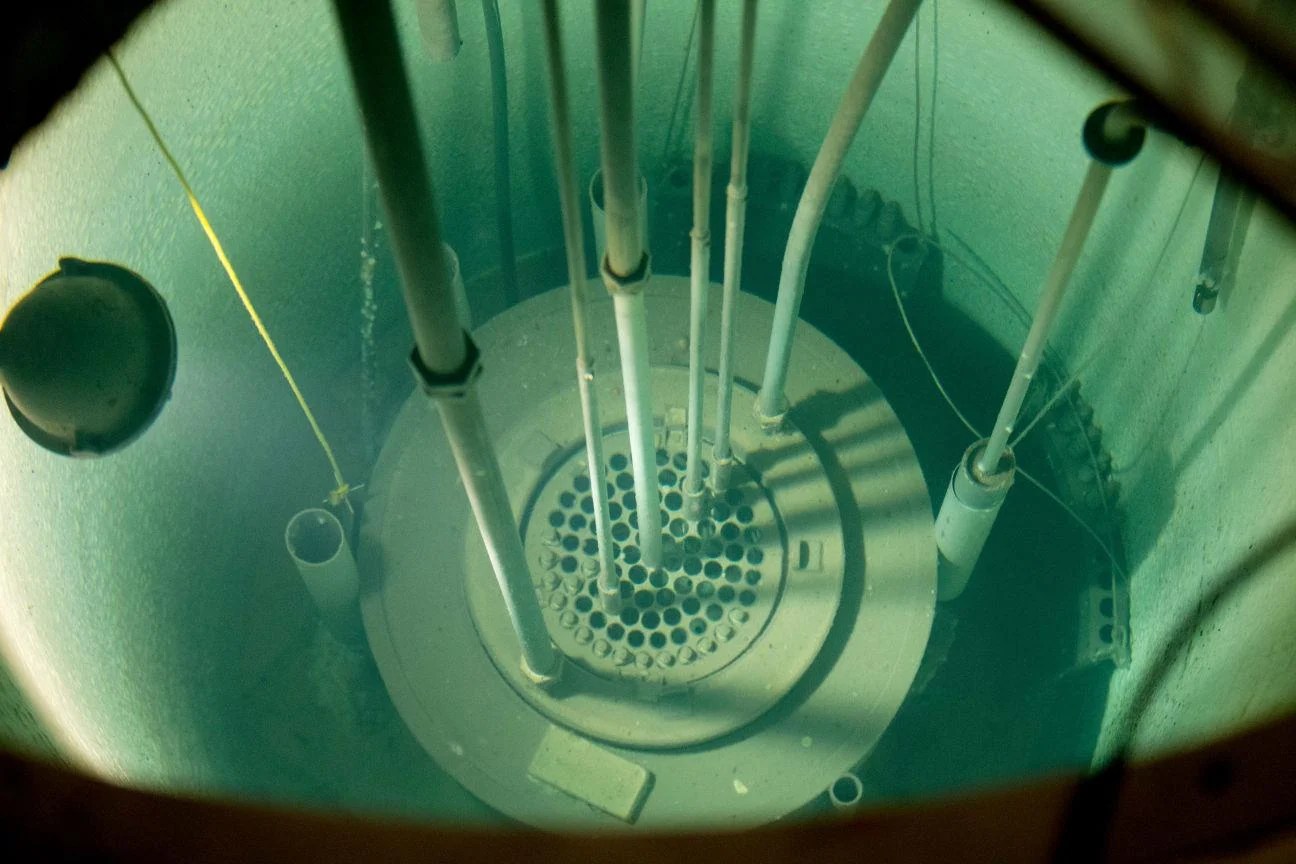

In the early 1960s, the Omaha VA hospital emerged as one of the centers of radioisotope research and diagnosis thanks to the nuclear reactor buried in its basement. The hospital purchased the low-power General Atomic reactor in 1959 at a total cost of $154,000, installation included. The hospital’s radioisotopes chief, Dr. Richard E. Ogborn, supervised a staff of about 30 and his facility was funded as a national laboratory from 1959 to 1965.

The reactor was used to bombard samples of blood, bone, and organs with neutrons, a process known as neutron activation analysis. By observing and measuring the decay rate of the gamma radiation, researchers can determine with great accuracy the type and amount of trace elements—for instance, iodine or sodium—present in the sample. The information gleaned from this procedure helped VA doctors understand the role of these elements in health and disease.

The ability of Ogborn’s lab to analyze the irradiated samples received a big assist in 1960 through the acquisition of another piece of equipment—the first desk-top computer to be used for medical research at VA. The computer enabled his team to process up to 5,000 samples a year.

Dr. Ogborn left Omaha in 1966 to become the director of VA’s newly minted Nuclear Medicine Service. Tragically, he died a few months later in June 1967. The reactor at the Omaha VA hospital remained in operation for another 34 years. It was finally shut down in 2001 due to security concerns soon after the September 11th terrorist attacks. In 2016, workers decommissioned and dismantled the reactor. All radioactive waste was removed and a final radiological survey confirmed that the site had been decontaminated.

Although Ogborn did not live to see it, the nuclear medicine program that he and Drs. Lyon and Mosely helped launch has become an integral part of the medical care VA provides to Veterans. Every year, thousands of VA patients undergo nuclear imaging procedures to diagnose medical problems or radiation therapy to combat disease. VA has been widely recognized as a pioneer in the field.

Perhaps the program’s greatest achievement came in 1977 when Dr. Rosalyn Yalow received the Nobel Prize in medicine for the work she started in the radioisotope unit at the Bronx VA hospital in New York in the 1950s. Her research in collaboration with Dr. Solomon A. Berson led to the development of radioimmunoassay, a revolutionary technique to measure hormones and other biochemicals in small samples of blood or tissue.

By Katie Rories

Historian, Veterans Health Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.