In August 1945, the United States detonated atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending World War II and ushering in the dawn of the Atomic Age. Two years later, the Veterans Administration started harnessing this technology for a very different purpose—to conduct medical research. VA’s use of nuclear energy to diagnose and treat disease expanded in the 1950s, culminating at the end of the decade in the installation of a small nuclear reactor beneath the VA hospital in Omaha, Nebraska.

The father of VA’s nuclear program was Dr. George M. Lyon, a Navy Veteran and member of the Manhattan project who joined VA in 1947 as Special Assistant for Atomic Medicine. His position had been established to help VA prepare for the evaluation of claims from Veterans exposed to atomic radiation. The year of his hiring, however, the Atomic Energy Commission began making radioisotopes available to medical investigators for clinical research under a strict licensing arrangement. Produced in a nuclear reactor, radioisotopes are unstable forms of chemical elements that emit radiation as they decay. They proved of tremendous value to researchers because their properties made it possible to study different physiological processes with great precision. To coordinate the use of this material in its hospitals, VA created a Radioisotope Section and appointed Dr. Lyon its first chief. By mid-1948, radioisotope labs were up and running at eight VA hospitals. That same year, Lyon recruited Dr. A. Graham Moseley, Jr., a chemistry professor at Marshall College in West Virginia, to be his deputy. Like Lyon, Moseley had held a war-time commission in the Navy and both men assisted with the nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific in 1946.

Dr. Moseley deserves much of the credit for the growth of VA’s nuclear medicine program. When Lyon was promoted in 1952, Moseley took over as head of Radioisotope Research and he continued to run the section until his retirement in 1966. During the 1950s, the number of VA hospital labs equipped to conduct medical research using radioisotopes grew to sixty. A survey of VA medical investigations at the end of the decade reported that more than 600 radioisotope projects had been approved. Researchers employed radioisotope tracer techniques to study such processes as coronary blood flow, fat digestion and absorption, and the rate of cholesterol synthesis within an autopsied human aorta. As the field matured, VA physicians increasingly employed radioisotopes for clinical purposes, too. For instance, radioisotopes were used to evaluate liver and kidney function, determine the location of brain tumors, and treat hyperthyroidism. In 1966, the year of Dr. Moseley’s retirement, more than 60,000 VA patients benefited from radioisotope diagnostic procedures while another 600 received therapeutic doses of radioisotopes. That same year, VA established a Nuclear Medicine Service in the Department of Medicine and Surgery to coordinate the clinical application of radioisotopes across 88 nuclear medicine clinics and hospitals.

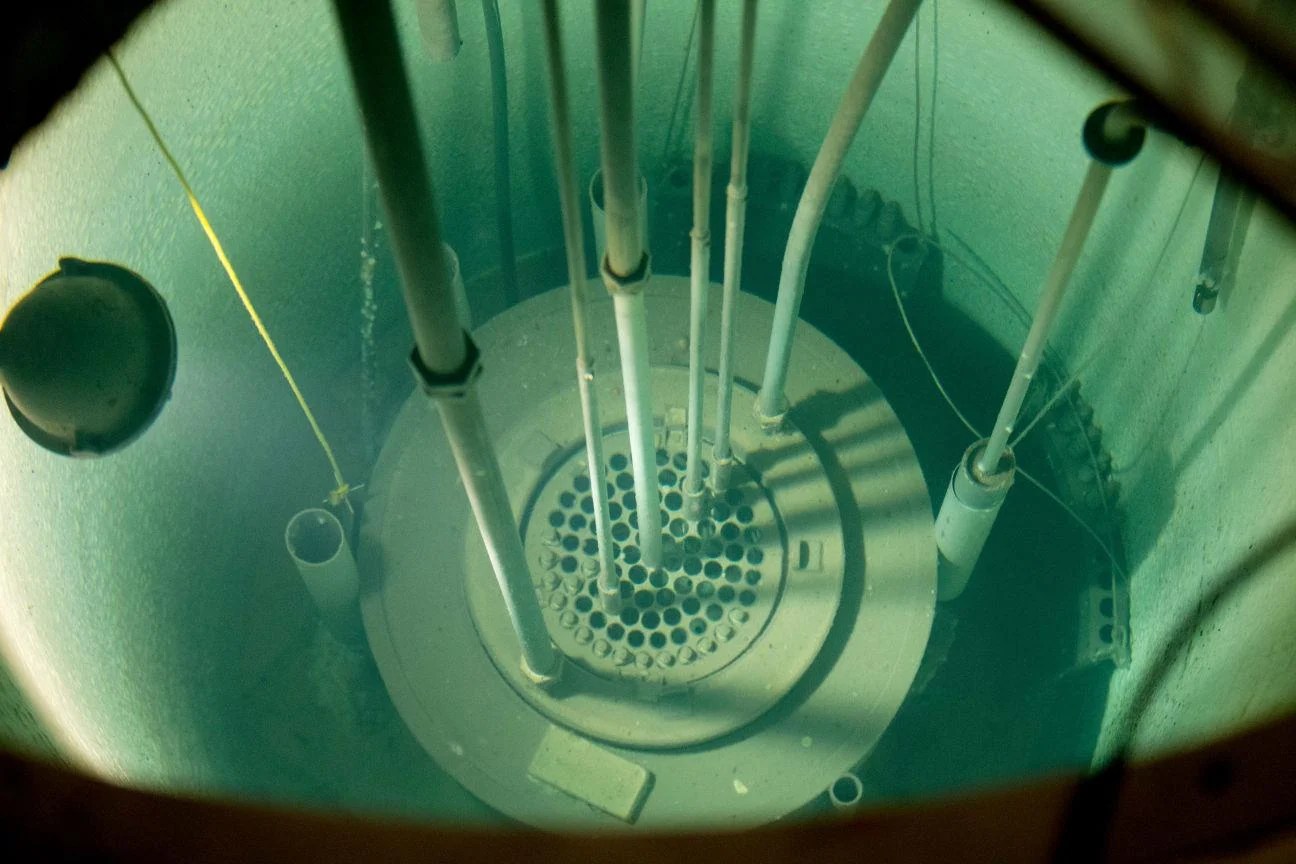

In the early 1960s, the Omaha VA hospital emerged as one of the centers of radioisotope research and diagnosis thanks to the nuclear reactor buried in its basement. The hospital purchased the low-power General Atomic reactor in 1959 at a total cost of $154,000, installation included. The hospital’s radioisotopes chief, Dr. Richard E. Ogborn, supervised a staff of about 30 and his facility was funded as a national laboratory from 1959 to 1965. The reactor was used to bombard samples of blood, bone, and organs with neutrons, a process known as neutron activation analysis. By observing and measuring the decay rate of the gamma radiation, researchers can determine with great accuracy the type and amount of trace elements—for instance, iodine or sodium—present in the sample. The information gleaned from this procedure helped VA doctors understand the role of these elements in health and disease. The ability of Ogborn’s lab to analyze the irradiated samples received a big assist in 1960 through the acquisition of another piece of equipment—the first desk-top computer to be used for medical research at VA. The computer enabled his team to process up to 5,000 samples a year.

Dr. Ogborn left Omaha in 1966 to become the director of VA’s newly minted Nuclear Medicine Service. Tragically, he died a few months later in June 1967. The reactor at the Omaha VA hospital remained in operation for another 34 years. It was finally shut down in 2001 due to security concerns soon after the September 11th terrorist attacks. In 2016, workers decommissioned and dismantled the reactor. All radioactive waste was removed and a final radiological survey confirmed that the site had been decontaminated.

Although Ogborn did not live to see it, the nuclear medicine program that he and Drs. Lyon and Mosely helped launch has become an integral part of the medical care VA provides to Veterans. Every year, thousands of VA patients undergo nuclear imaging procedures to diagnose medical problems or radiation therapy to combat disease. VA has been widely recognized as a pioneer in the field. Perhaps the program’s greatest achievement came in 1977 when Dr. Rosalyn Yalow received the Nobel Prize in medicine for the work she started in the radioisotope unit at the Bronx VA hospital in New York in the 1950s. Her research in collaboration with Dr. Solomon A. Berson led to the development of radioimmunoassay, a revolutionary technique to measure hormones and other biochemicals in small samples of blood or tissue.

By Katie Rories

Historian, Veterans Health Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the 19th century, the federal government left the manufacture and distribution of prosthetic limbs for disabled Veterans to private enterprise. The experience of fighting two world wars in the first half of the 20th century led to a reversal in this policy.

In the interwar era, first the Veterans Bureau and then the Veterans Administration assumed responsibility for providing replacement limbs and medical care to Veterans.

In recent decades, another federal agency, the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA), has joined VA as a supporter of cutting-edge research into artificial limb technology. DARPA’s efforts were spurred by the spike in traumatic injuries resulting from the emergence of improvised explosive devices as the insurgent’s weapon of choice in Iraq in 2003-04.

Out of that effort came the LUKE/DEKA prosthetic limb, named after the main character from "Star Wars."

History of VA in 100 Objects

American prisoners of war from World War II, Korea, and Vietnam faced starvation, torture, forced labor, and other abuses at the hands of their captors. For those that returned home, their experiences in captivity often had long-lasting impacts on their physical and mental health. Over the decades, the U.S. government sought to address their specific needs through legislation conferring special benefits on former prisoners of war.

In 1978, five years after the United States withdrew the last of its combat troops from South Vietnam, Congress mandated VA carry out a thorough study of the disability and medical needs of former prisoners of war. In consultation with the Secretary of Defense, VA completed the study in 14 months and published its findings in early 1980. Like previous investigations in the 1950s, the study confirmed that former prisoners of war had higher rates of service-connected disabilities.

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.