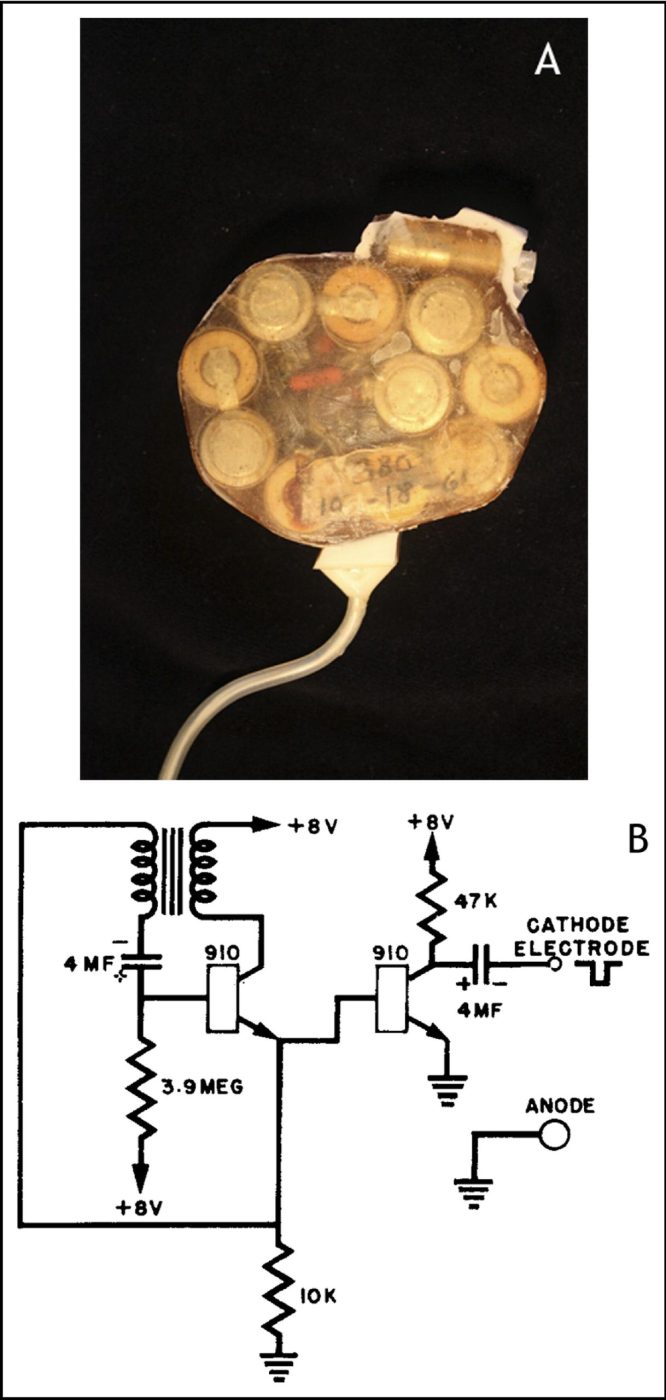

In 1960, a VA research team led by surgeon William Chardack inserted what he described as a “battery-operated gadget about twice as big as a spool of Scotch tape and much the same shape” under the skin of a patient suffering from a complete heart block. The compact “gadget”- better known as the cardiac pacemaker – sent electrical signals to stimulate the heart and help it maintain a regular rhythm. A bundle of ten mercury zinc cells generated the pulses. While other researchers had created external pacemakers, Dr. Chardack’s device was revolutionary because it was implantable and powered by its own battery pack. The internal cardiac pacemaker developed by his team transformed the field of cardiac medicine.

Work on the pacemaker began in 1958 at the VA hospital in Buffalo, New York. Dr. Chardack’s team included another surgeon, Andrew Gage, and electrical engineer Wilson Greatbatch. Together, they focused on the many possibilities of electricity in medicine. The group was known as the bow tie team on account of their penchant for wearing bow ties to work each day. It was the engineer Greatbatch who actually designed the pacemaker and he built the first 50 by hand in his backyard workshop. They tested a prototype of the device on a dog so they could observe the benefits of cardiac electrotherapy. Two years later, they were ready to implant the cardiac pacemaker in a human. The operation was a success and the man lived for another two years before dying of unrelated causes. Subsequent patients who received the pacemaker lived for as long as 20 years after the surgery.

The bow tie team continued to refine their invention in the 1960s and early 1970s. In 1972, with Dr. Chardack assisting, Dr. Gage implanted the first nuclear-powered cardiac pacemakers in patients at the Buffalo VA hospital. The same year, Greatbatch pioneered the use of long-lasting lithium-iodine cells as a power source for pacemakers.

Although surgical techniques and pacemaker technologies have evolved over the years, the basic design remains similar to the device introduced to the medical world by Dr. Chardack and his collaborators in 1960. The cardiac pacemaker developed by VA researchers has improved the length and quality of life for thousands of Veterans and millions of people worldwide.

By Parker Beverly

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, Veterans Health Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.