In July of 1862, Congress authorized President Lincoln to establish the first national cemeteries, dedicated “for the soldiers who shall die in the service of the country”. This was before there was a federal agency dedicated to Veteran’s affairs, so the responsibility fell to the Army Quartermaster General (AQG). This led to the first standardization of burial practices for U.S. war dead, and though the practices changed through the decades, it represents the first model of excellence to honor Veterans upheld by the National Cemetery Administration (NCA) today.

When the United States joined World War I, the American Grave Registration Service (AGRS) set out to repatriate (bring back the remains of) all fallen Americans. This changed when General John J. Pershing expressed his desire for proper cemeteries and monuments to be dedicated to his men on European soil. So the government gave surviving family members of fallen soldiers the choice for their relatives to be returned for burial in the U.S., or for internment in cemeteries constructed at the battlefields.

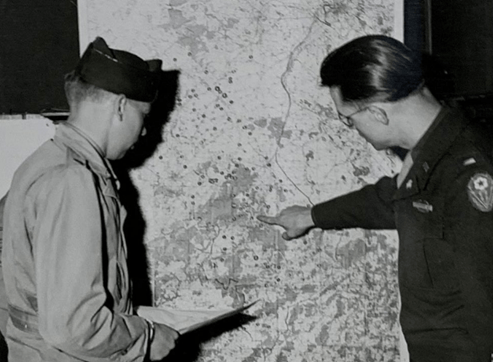

During the Second World War, the national cemetery system faced an influx of burials not seen since their founding. Even so, there was a degree of uncertainty where fallen American soldiers would be put to rest. Some assumed families of the deceased would prefer for their loved ones to be returned to the United States for burial, but the Western Europeans were more than happy to continue to care for American war dead in the way they had after the First World War. Ultimately, surviving family members were once more given a choice in the disposition of their loved ones’ remains; they could be buried in an overseas cemetery permanently cared for by the American Battlefield Monuments Commission (ABMC), or they could be returned home for reinternment in a national or local cemetery.

Families waited years before their loved ones were returned. This was especially true when remains could not be identified. “Unknown” individuals were usually buried overseas, but modern science allows for remains previously unidentified to be recognized and returned home. In other words, the work to return those who died overseas continues today. Take for example the story of Private James Loterbaugh, an American soldier from Roseville, Ohio. He died in Germany in 1944, but his remains could not be positively identified until 2023, when the DPAA (Defense POW-MIA Accounting Agency) confirmed their identity. In the summer of 2025, more than 80 years since his death, James Loterbaugh was laid to rest in Dayton National Cemetery.

Museums collect artifacts because of the stories they tell. The following objects from the National VA History Center tell the story of how families of fallen World War II soldiers chose to honor their loved ones and preserve the memory of their service forever.

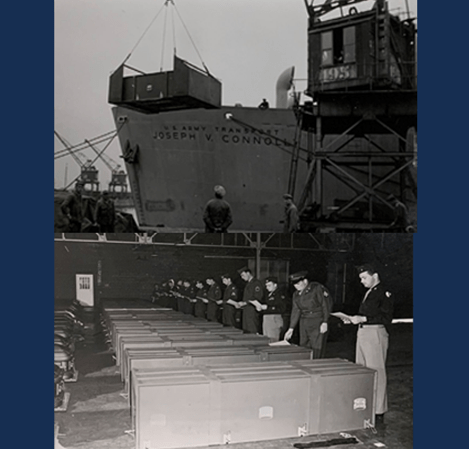

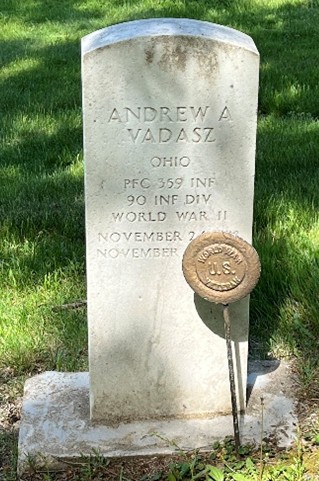

First is a large metal and wood box with handles and latches on each side. The text on the box reads “ANDREW A. VADASZ, PFC USAGF, FOR GIVEN FUNL. HOME, S PROSPECT ST., HARTVILLE, OH”, telling us that this is the case used to transport the remains of a fallen soldier back home to Ohio.

Private Andrew Vadasz was born in 1918, and his short but meaningful life would end in Eastern France in 1944. In July 1948, local newspapers reported the arrival of a ship transporting the remains of more than 200 Ohioans, including Private Vadasz, back to the U.S. Four years after his death, Pvt. Andrew Vadasz was laid to rest in his hometown cemetery, with the National Cemetery standard headstone.

Private Vadasz’s family chose to honor their son by returning him to Ohio. Other families who lost loved ones in the war chose for their remains to be honored in the places where they died.

This flag was presented to the family of Flight Officer Mark O. Lapolla, from Suffern, New York. F.O. Lapolla’s plane went missing in January 1945 and was pronounced dead the following year. His family chose for their son to be interred in the Florence American Cemetery in Florence, Italy. In such cases the families were given the National Colors which were draped over their loved ones’ casket prior to burial, folded according to tradition.

Over the last 250 years, loved ones lost in war have been remembered and honored for their sacrifice in many ways. Our team at the National VA History Center shares the story of America’s service to Veterans by preserving this history for future generations. Understanding the value of these stories, The National Cemetery Administration describes the WWII Burial Program as “a promise kept to those who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country.” (NCA 2020). Inspired by those who came before us, the VA History Office continues to discover stories of the promises kept to those who served.

For more information about the WWII Burial Program, check out the NCA Publication written as part of the World War II 75th Commemorative Series here.

Share this story

Related Stories

Curator Corner

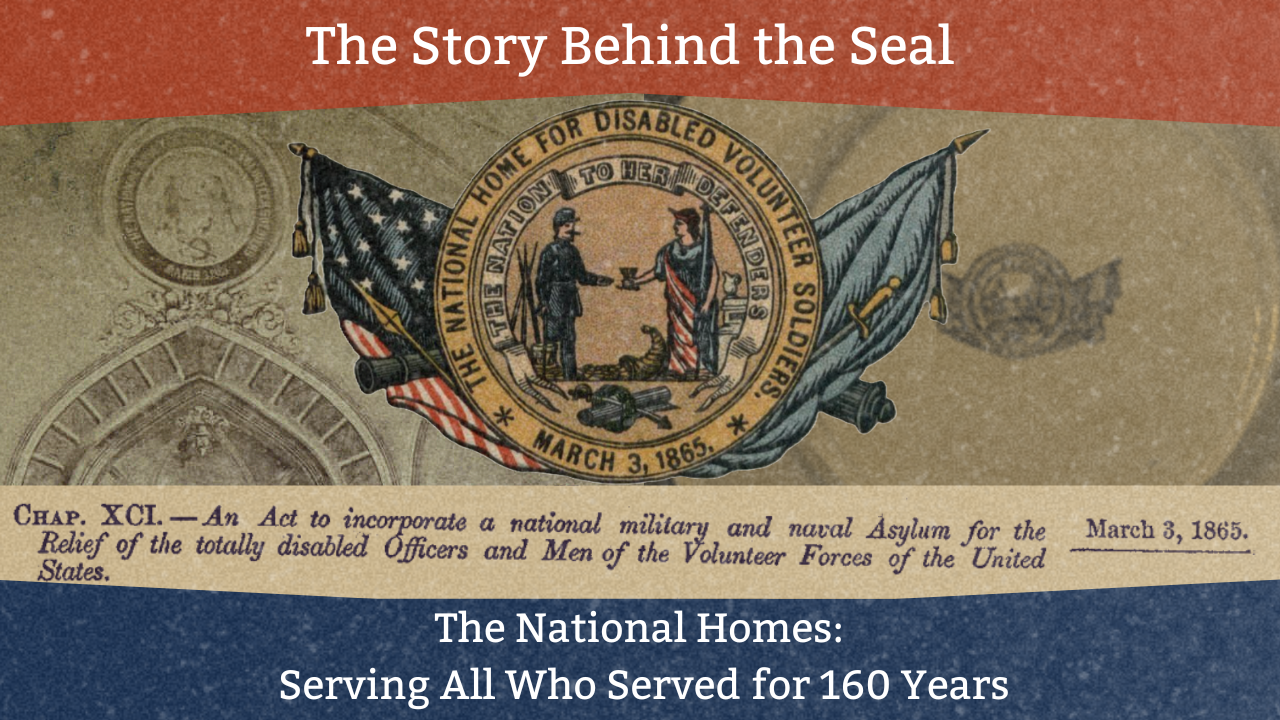

The Story Behind the National Homes’ Seal

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers turns 160 years old in 2025. The campuses are the oldest in the VA system, providing healthcare to Veterans to this day.

At the time of their establishment, they were the first of their type on this scale in the world. Within the NHDVS seal is the story that goes back 160 years ago.

Curator Corner

What’s in the Box? Fire Safety and Prevention at the National Homes

Fire safety may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about Veteran care, but during the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers period (1865-1930), it was a critical concern. With campuses largely constructed of wooden-frame buildings, housing thousands of often elderly and disabled Veterans, the risk of fire was ever-present. Leaders of the National Homes were keenly aware of this danger, as reflected in their efforts to establish early fire safety protocols.

Throughout the late 19th century, the National Homes developed fire departments that were often staffed by Veteran residents, and the Central Branch in Dayton even had a steam fire engine. Maps from this era, produced by the Sanborn Map Company for fire insurance purposes, reveal detailed records of fire prevention equipment and strategies used at the Homes. These records provide us with a rare glimpse into evolving fire safety measures in the late 19th and early 20th Century, all part of a collective effort to ensure the well-being of the many Veterans living there.