North Vietnamese Army Divisions crossed the border of South Vietnam and rapidly advanced toward Saigon in March 1975. In a desperate attempt to stop the enemy from taking the capital city, President Nguyen Van Thieu ordered the Army to defend Xuan Loc, 20 miles northeast of Saigon. From April 9 to April 21, 1975, the South fought valiantly against the invaders but could not hold them back. Thieu, who had led the Republic of South Vietnam for eight years, resigned and left the country.

By April 27, the Communists had surrounded Saigon. Many who worked for U.S. agencies were counting on their sponsors to take them out of the country. I was a major and physician in the Army of Vietnam Medical Corps at the Saigon Military Hospital. I had no connections, but my father-in-law did. He was a political leader and former Army general who had attended the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He arranged with the CIA for my wife, his daughter, to escape on April 28. When I said goodbye to her, we were only married for 16 months, and she was pregnant. My father-in-law said the U.S. Embassy was responsible for us, and Americans had a plan for everything. He was confident the CIA would take us out the next day.

The house where we waited for instructions was close to the embassy. It belonged to a South Vietnamese senator the CIA had already flown out of the country. Before entering, my father-in-law whispered, “Careful, the maid could be a Viet Cong spy.” At noon on April 29, the phone finally rang. A car would pick us up in front of the embassy in ten minutes.

Leaving the house, we saw Marine helicopters landing and lifting off from the embassy’s grounds. People were besieging the guarded entrance, attempting to climb the 15-foot high walls topped with coils of barbed wire. The crowd was a solid mass, hundreds deep, with desperate Vietnamese pushing forward. We couldn’t get anywhere near the embassy gate. All night, we stood in the crowd and waited, still convinced the Americans would save us. President Richard Nixon had promised to aid us if the North invaded. Weeks before, the head of the U.S. Information Agency announced on Saigon television that America would not abandon us.

Early in the morning of April 30, we heard North Vietnamese tanks in the streets. The enemy was closing in. We stopped at the Catholic Archbishop’s house, where about 50 people were hiding in the basement listening to the radio. Suddenly, a different announcer was on the air. That could only mean the enemy had seized the radio station. There would be no rescue for us. The general became distraught and said I would be in great danger if the Communists found me with him and that I should be on duty at the hospital. He cautioned me not to say anything about my wife. If they discovered I was married to the daughter of a staunch anti-communist, it would go badly for me. I didn’t know what to say. I felt powerless and looked at my feet. He wrapped his arms around me. I could feel his compassion. Quickly, he turned and left. At that moment, it struck me that my life would change.

Returning home, I told my mother that the arrangements for my escape had failed, but my wife had gotten away. She became angry. My mother said that for generations our family had been Catholic and followed the teachings of Confucius, including the loyalty of a husband and wife to one another. Confronting me, she wanted to know why my wife left without me when it was her duty to stand by me. I tried to explain that if she had stayed, her future, our child’s future, like mine, would be in doubt.

I talked with my brother, a distinguished physician and Army captain, about whether to wear our uniforms to the hospital. It was hard to know what to do. We decided to burn every document connecting us to the Americans, including photos from when I was selected to train at the West Haven Veterans Hospital in Connecticut from 1967 to 1969. While in the United States, I watched the nightly news about America’s widespread opposition to the war. It was troubling to see the flag-draped caskets of U.S. soldiers arriving at airports around the country. It was no surprise when President Lyndon Johnson said he would not run for president. I knew then the war would not end well for South Vietnam. A colleague at the hospital wanted to help me cross into Canada. He said returning to Vietnam would not change the direction of the war. I understood what he meant but could not accept his offer. I had sworn an oath to my government and was obligated to return to my country. Within the ethical framework of Confucianism, there is a relationship between the ruler and the subject. For me, the ruler was the government of South Vietnam. I was the subject.

There was chaos in the streets when my brother and I made our way to the hospital on the morning of April 30. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer. On the speaker system, I urged patients to stay calm and directed nurses to remain at their stations.

At 10:24 a.m., the radio reported the surrender of Saigon. The hospital adjutant asked me whether to lower the flag of South Vietnam. Solemnly, sadly, I said yes. A truck filled with North Vietnamese soldiers stopped at the hospital’s main entrance. The officer in charge shook my hand and bowed slightly to the Buddhist priest. He ignored the Catholic priest. Communists viewed Catholics with contempt for opposing them. I told the officer we were treating South and North Vietnamese soldiers. He nodded. Then, he ordered his troops to surround the building.

Doctors and medical personnel from the North began arriving at the hospital. They questioned me about how I profited from my former position in the Army. I found the question insulting. I told them I was not wealthy, worked only at the hospital, and owned no house or car. I said they should investigate if they didn’t believe me. WhyI served in the armed forces was another question. I explained that accepting a government scholarship obligated me to serve in the military. One doctor pulled me aside and, speaking in hushed tones, wanted to know what I thought about communism. I hesitated to answer. I said, “You don’t respect religion, and your orders come from abroad.” He was silent. Although what I said was true, in time, I painfully realized I should have never said that.

It became apparent that the Northern doctors and medical personnel did not have the same institutional training as we had in the South. Their experience was limited to the jungle. In one instance, one of their soldiers attempted to kill herself by overdosing on sleeping pills. She was comatose. Their doctors didn’t know what to do and asked for help. Fortunately, our physicians soon returned, and I became their unofficial head. I was permitted to briefly leave my post at the hospital to visit my family. While heading home, an aide to my father-in-law recognized me on the street. He told me that, for the moment, authorities had confined the general to his house. I was relieved to learn he was still alive.

Six weeks later, in June, I was ordered to report for “reeducation,” with instructions to bring money and food. Before leaving the hospital, the head Communist physician beckoned me and said I would return in a month. Having read about the aftermaths of the revolutions in Russia and China, I doubted that. Whatever was ahead, I knew it would be hard, and I prepared for the worst.

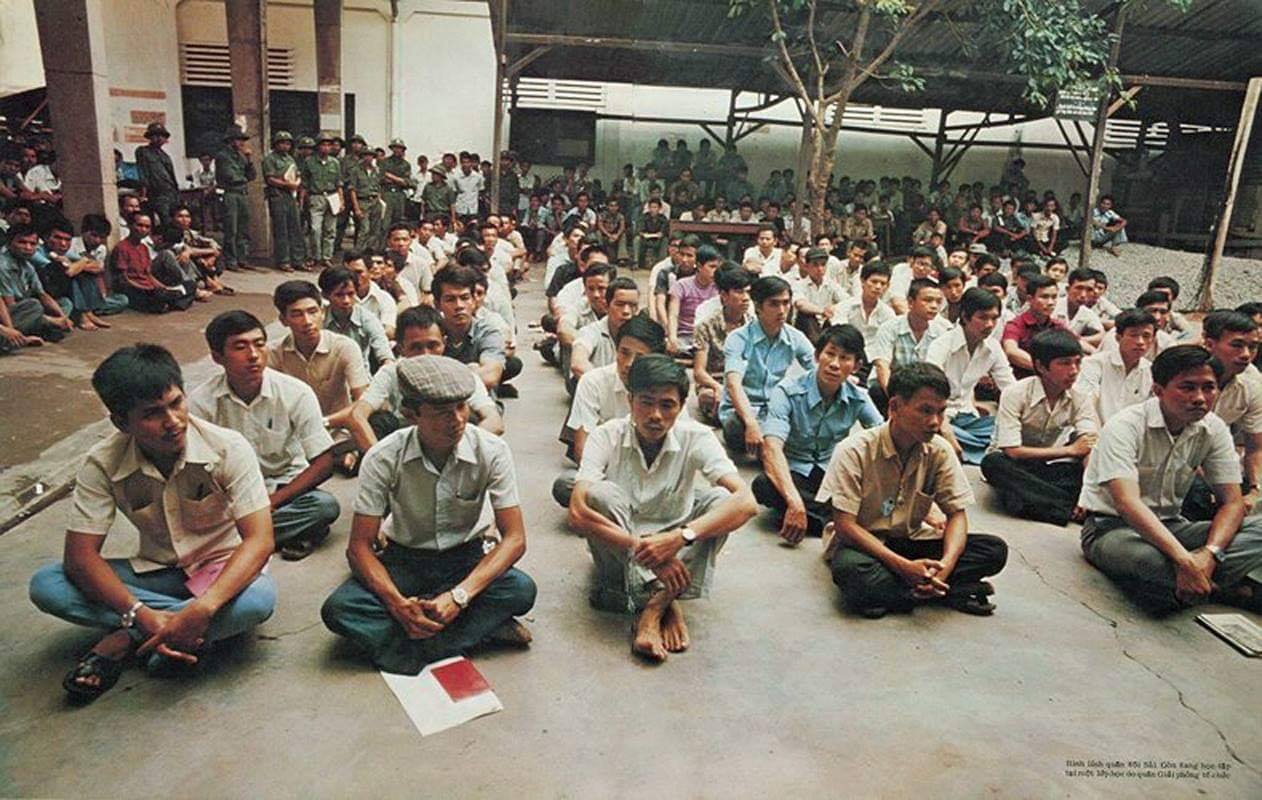

I didn’t know then that as early as 1961, the Communists had planned for reeducation camps to teach the ways of the new government. Tens of thousands of South Vietnamese who had supported the United States or the former government were now being sent to these camps─not just military officers, like me, but also government officials, teachers, religious leaders, artists, and writers. The higher the rank, the longer the imprisonment. There were between 90 to 100 camps.

Ironically, my initial assembly location was a Catholic school with pictures of Jesus on the walls. Thinking he was already at reeducation, a fellow Army officer asked when it would start. The official said that this was not the place. Agitated by being questioned, the Communist viciously accused the man of never having worked and of looking down on subordinates. Turning to the rest of us, the official said reeducation would rehabilitate us to reenter society as honest people. A pharmacist I recognized from the hospital gave me a look, but I did not acknowledge him. I didn’t want to draw attention to us.

I left for Long Giao Camp in a Chinese truck to begin the formal reeducation program that night. It was northeast of Ho Chi Minh City, in southern Vietnam. During the war, it was a New Zealand military base. The camp cadre organized us into groups of ten to live and work together. We were not allowed to talk with prisoners in other groups, and we soon realized each group had a spy. I longed for my wife. My heart went out to the father and son who were in different groups and could not speak to each other. I was forbidden to use my medical skills to treat fellow captives. Meals were always the same: rice with some salt, a bit of cabbage, and manioc. Manioc is a root plant that fills you up but has no nutrients. We never had enough to eat. There was an understanding among us: if it moved, eat it like giant centipedes and grass lizards.

The objective of reeducation was to wipe out our knowledge of democracy. We had no rights─only to obey. Well-trained and rehearsed instructors lectured us. There were nine topics, one each week. Lectures included their triumphant victory over us and emphasized the single-minded commitment of other countries to communism. We had to clap after every lecture!Group discussion was mandatory. When called upon to respond to a lecture, I parroted whatever the instructors said.

They told us our Army was shameful, that it was a product of the French─trained and nurtured by the Americans. Serving in the Army of South Vietnam, even one day, was considered a crime against the people and deserving of death.According to them, the government of South Vietnam had been an instrument of the Americans. Capitalism was described as the exploitation of the working class by wealthy colonialists who dominated poor countries, and the United States was the chief imperialist and policeman of the world.

I had to write a declaration containing information about my whole family, including how much money they had and how they died. The writing took weeks, and the final document had to be perfect. The most absurd requirement was to confess my alleged crimes under the former “puppet” government to the authorities and the other captives so they could criticize me. Admitting many crimes earned praise from the cadre. Self-criticism was last. I had to apply the principles of communism to my life from elementary school to the present. My statement had to contain sincere words and express repentance. One Air Force pilot was so eager to appear repentant, he wrote that he dropped more bombs than his aircraft could even carry!

After the lectures, declarations, confessions, and self-criticism, we were allowed to write letters for the first time. I wrote to my mother, but the underlying meaning of the words was for my wife. I desperately wanted her to know she was always in my thoughts. If the authorities knew that my wife was in America, they would confiscate my mother’s home. My letters praised my captors to a ridiculous degree. They expected it.

Allowing us to write letters raised our expectations the government would release us, but months passed without the cadre mentioning it. Then, the guards claimed it was too dangerous to let us go. We had destroyed the people’s rice fields, wasted the country’s resources, and contributed to many deaths. They insisted we needed protection because the people would kill us if we returned to our homes.

To deny us time to organize and resist, they moved and mixed us with prisoners from other camps. In December 1975, along with other higher-ranking officers, I was moved to Tan Hiep, my second camp, north of Ho Chi Minh City, in southern Vietnam. During the war, it held North Vietnamese and Viet Cong soldiers. Now, we were their captives. The camp had 25 concrete buildings with tin roofs. Multiple barbwire fences and mines surrounded it. Thirty-minute visits were sometimes permitted. My mother and sister came. It was the first time I had seen them since reporting for reeducation seven months earlier.

When walking to the fields to work, I exchanged friendly glances with villagers. Despite what the Communists said about the people hating us, I never got that feeling. On the contrary, people felt sympathy for us. We no longer resembled officers. Our clothes were torn. Few of us had shoes. Once, a man stopped on the road, pretending to fix his bicycle. When guards weren’t looking, he said softly, “How are you?” From passing trains, passengers waved to us from open windows and made the Vsign. Others riding on the tops of rail cars cheered us. These signs bolstered my spirits. I was at Tan Hiep Camp until April 1978, when the government moved me to my third camp.

Bui Gia Map in southern Vietnam was in a remote area near the Cambodian border, northwest of Ho Chi Minh City. When we arrived, it was late. Trucks left us in a thick jungle so dense it felt engulfing. There were no shelters. Quite unexpectedly, I found a clear spot to pitch my tent. It rained hard that night, and water leaked into the opening. I used my poncho to seal the entrance. Lying there in the dark, I wondered how I had found such a good spot on the jungle floor. Then it came to me. In that part of the country, the custom is to clear an area in the jungle and bury the dead in unmarked graves. Was there a body under me? With no light coming in, I felt entombed.

The next day, with makeshift tools we started building shelters out of bamboo and palm branches using vines for nails. To supplement our rice diet, we tilled the soil to grow maize. The lack of food always made me feel weak. I frequently fell asleep on the ground, even when it was cold. Often, I was too tired to move. There were other days when I was so hungry that sleep was impossible. Still, I felt luckier than many others. I was smaller and thinner and didn’t need as much food. There was a little creek nearby where hundreds bathed. If our group was the last to leave, happiness was finding a cup of clean water.

My best moment in the camps was receiving a six-month-old postmarked letter from my wife in America. The letter came from a relative in France, who sent it to my mother in Ho Chi Minh City, who mailed it to me. Inside was a picture of my child. I had a son! Seeing his image, I wept with joy. That photo, my Catholic faith, and my belief in the teachings of Confucius filled me with the hope for a better tomorrow. I grew to accept my fate: the war, my family situation, and imprisonment. I understood these realities were beyond my control.

The Socialist Republic of Vietnam desperately needed doctors, and in December 1978, the government decided that military physicians were technically non-combatants and released us. After over two and a half years in three camps in southern Vietnam, the government permitted me to return to Ho Chi Minh City. My faith in a better tomorrow was about to come true. That’s what I thought.

The government and the society I returned to had fundamentally changed from when I left in 1975. The authorities exercised complete control over every aspect of living. Everyone was in an organized group: young adults, workers, seniors, and families. All groups met weekly. The local police chose the leaders—who acted as their informants. My identification stated I was a former major in the armed forces of the rebellious government and a Nguy. The word in English closest to it is traitor. Nguy means someone who turned against the country and worked for an illegal government. I was required to report to the police every month.

Before the war, I was a visiting professor at what is now the Ho Chi Minh City Medical University, the largest teaching hospital in the country. When I applied for a position there, the director was impressed with my credentials. However, when I showed my identification to the hospital personnel clerk, he said it was inconceivable for a Nguy to be on the staff of this prestigious hospital. I wondered if this is what the camp cadre meant when they said all would participate in the collective ownership of society.

After the rejection from the first teaching hospital, another accepted me. When physicians who were my former students passed in the halls, they winked cautiously. They were being careful not to be perceived as associating with me. My superior was a doctor who was an opportunist. When the Communists took over, it seemed she transformed into a revolutionary overnight. An encounter at the hospital revealed her attitude toward me. While talking to nurses in the hallway, I was handed an envelope with my name on it. She happened to walk by and rudely grabbed it, tore it open, and read the contents. It was a poem from a patient thanking me for my care! Embarrassed, she returned the opened letter and hurried away. Her behavior was a sign the authorities were watching me. I was sure of it when I stopped at the hospital to visit a patient on my day off. I heard the police checked if I had been officially on call. I redoubled my efforts not to talk much—not to former students or friends. Revealing my real feelings was too dangerous. I realized my chance to reunite with my family depended on keeping a low profile.

In 1979, the United States, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees signed the Orderly Departure Program to permit immigration. One objective of the agreement was for family reunification. Hoping the government would let me leave, I asked my wife to apply for me.

During the Vietnam War, the People’s Republic of China supported the North Vietnamese. However, when the war ended, relations between the two countries deteriorated and reached a breaking point in 1978. The Socialist Republic of Vietnam invaded and occupied Cambodia, ending the rule of the Chinese-backed Khmer Rouge. In response, Chinese forces crossed the border into Vietnam in 1979. The hospital director ordered me to set up a small infirmary with medical supplies and a surgeon on Vietnam’s border with China. When the director visited, he saw me pulling water from the well and collecting wood for the kitchen. He commented favorably on my simple life and brought up my return to the hospital. The director knew my wife was in the United States. He said the government could intervene with the Americans to send her back, allowing me to keep working at the hospital. I was silent. As much as I wanted to be with my wife and son, I would not have them live under communism.

When I returned to the hospital from the infirmary on the border in late 1979, there was a notice for me to report to the Ho Chi Minh Office of Culture─actually the office of the secret police. People interrogated by them were often never heard from again. Recently, several high-profile physicians managed to escape the country. I did my best to cover their absence as long as I could. I wanted to escape too, but the cost was $1,500 to $2,000 in gold─a fortune for me! At first, I thought the secret police intended to question me about those who had fled. Instead, the official brought up my wife and asked how I wanted to solve my family situation. I told him I hoped the government would let me join them. The questioning then turned to my resources. I told him I earned the equivalent in rice of $15 a month at the hospital. To help me subsist, my mother sold her jewelry, furniture, clothing, and my only jacket. My wife had left a pair of shoes behind. The heels were uneven because she had a back condition. My mother even had to sell them. Despite my explanation about my financial situation, I was sure he still suspected I was planning to escape to be with my family.

I felt empty when learning what happened to my brother, the physician. While attempting to escape, his overloaded boat encountered a terrible storm that swept the vessel’s food and water overboard. My brother and others died of hunger and thirst. To stay alive, the survivors ate the dead. Out of respect for my brother, they did not eat him. Instead, they tore the flesh from his thighs to use as bait to catch fish.

The party chief liked to tell others that although separated from my wife and young son, my letters were never about political matters. By this time, I knew that if I wrote about my true feelings, the authorities would never let me leave.

I had asked my wife to apply for me to join her under the Orderly Departure Program. I reached the depths of despair when, instead of completing the application, my wife wrote she was divorcing me. I was heartbroken. But I realized there was no guarantee the Communists would free me. She was still young, and raising a child alone was difficult. I was thankful she was raising our son.

As the years passed, each new hospital director wanted me to assume control of a major medical department. The hospital administration always assured me they would not stand in the way if the government said I could leave the country. I had no choice but to accept the positions. For instance, I was made Chief of Intensive Care. Another time, I replaced a long-time party member as Chief of Medicine. Appointing a Nguy for these positions was extraordinary. Once, I was even named “Physician of the Year,” but I was always under their watchful eyes. I was surprised when the medical school associated with the main hospital in Ho Chi Minh City, where I had taught before my imprisonment, asked me to be a guest lecturer again.

In 1988, the Ho Chi Minh City official in charge of intellectuals sent a car for me. I was nervous about the meeting because I had heard U.S. bombs killed her husband. She began by talking about medicine. Slowly, the conversation turned to my political attitude. She wanted to know how I felt about the government. I was careful about my answers. I repeated what the authorities had told me about the revolution’s interests to rebuild the country, reconcile the nation, and protect families. I softly reminded her that I had served the government for over a decade and had never seen my son. After several sessions, she seemed to accept my answers and gave up trying to persuade me to stay and, as she put it, continue to pursue my medical career in Vietnam.

In 1989, the Orderly Departure Program included a new provision. Prisoners who had been in the camps for three years could now come to the United States. I was in the camps for close to three years and might have qualified, but I had to be married. Soon after that announcement, the U.S. delegation managing the program wanted to meet with me. When I arrived, the official had my file on his desk. He looked at me, smiled, and told me to have patience a little longer. There was another provision under consideration for those who did not have three years in the camps but had trained in the United States.

Two years later, in December 1991, at 56, my faith in a better tomorrow came true. I arrived in America. And, for the first time, I embraced my 16-year-old son. It was too painful to share the details of my captivity with him. I only said that the government would not let me leave.

After qualifying as a medical doctor in the United States, I started a private practice serving a growing Vietnamese community in Atlanta. Over the years, I regularly traveled to Vietnam with a team of other volunteer doctors to treat the medically underserved. I am almost 90 now, too old to return to the country of my birth─torn apart by war.

For most of my life, I have rarely spoken about what it was like facing the Communists. The truth is I didn’t want to remember. Now, with my life growing short, I hope my story can be a voice for the tens of thousands with untold stories from this period from among the two million Vietnamese living in America today.

___________________________________________________________________________

Mike Sunshine is a retired U.S. Army Reserve colonel, Vietnam Veteran, and Army War College graduate. After a business career in marketing communications, he received an appointment to the Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Moving to the State Department, he served 46 months in the Middle East, first in Iraq and later in Afghanistan. His last posting was with the Multi-National Force and Observers in Sinai, where he was a peacekeeper overseeing the military treaty between Israel and Egypt.

Published with the permission of the author. Copyright © by Mike Sunshine 2023. All rights reserved. No part of this narrative may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the author.

By by Major Dich Van Nguyen

As told to Mike Sunshine