The U.S. Naval Asylum in Philadelphia was the first federal facility to provide institutional care for disabled and elderly Veterans. In 1811, Congress directed the Navy Department to establish such a home for the benefit of “disabled and decrepit Navy officers, seamen, and marines.” Funding was to come from the pot of money collected under an earlier law authorizing the deduction of 20 cents from the monthly pay of all sailors and Marines for the construction of naval hospitals. More than a decade would pass before workers broke ground on the building.

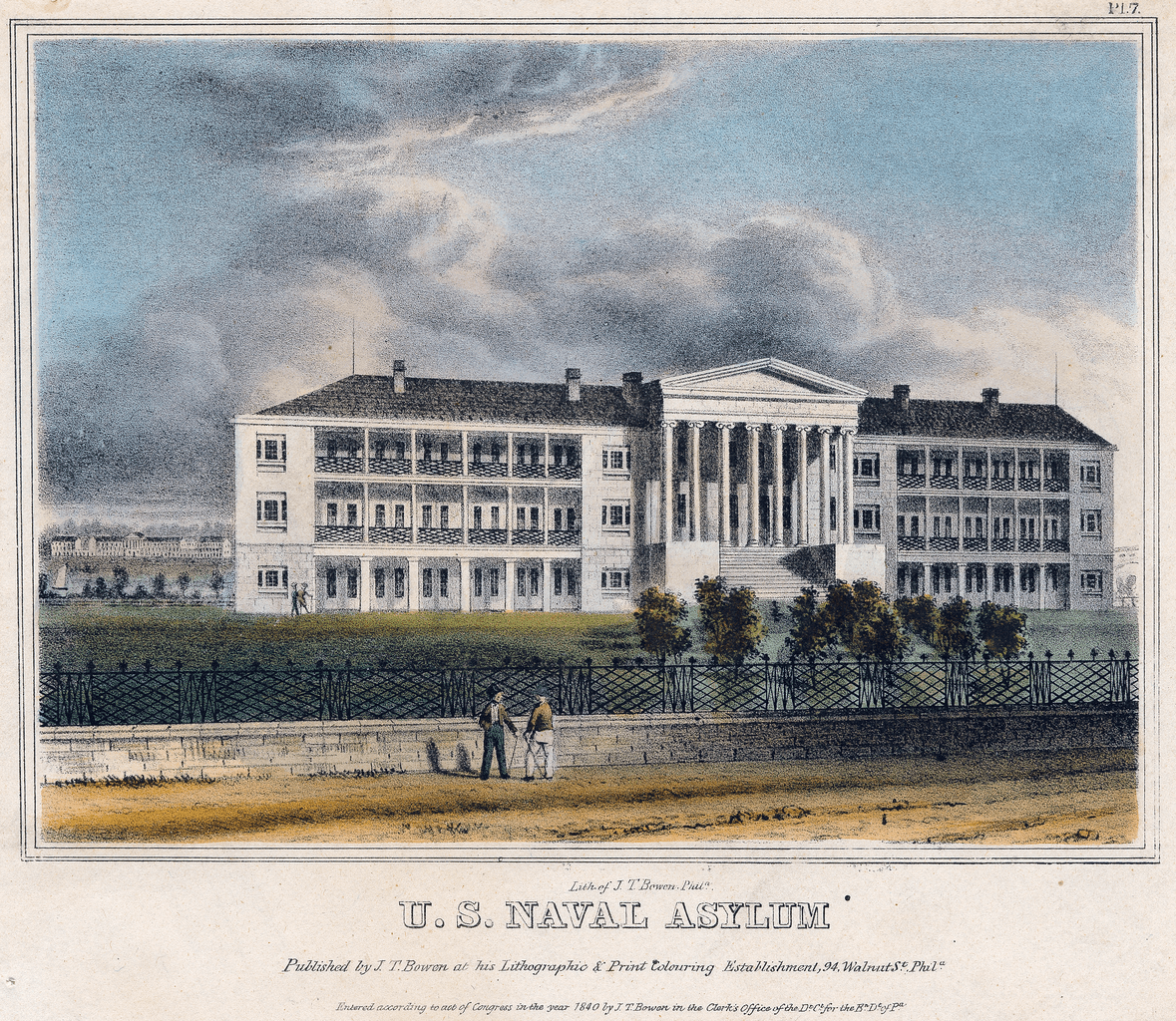

William Strickland, the noted Philadelphia engineer and supervising architect for the federal government, designed the structure in the popular Greek Revival style, which symbolized democracy to Americans. Construction started in 1827 but proceeded slowly due to funding problems. In 1834—some 23 years after the original act passed Congress—the Naval Asylum finally opened its doors to beneficiaries.

A senior naval officer summed up the purpose of the asylum in almost poetic terms when he wrote in an 1858 report: “It is fitting that a beneficent government should thus reward faithful services with the necessary comforts of life and provide for the wants of the last hours of these veteran servants of our country.”

The capacious building could accommodate up to 400 people in its 180 rooms, although some of this space was used as a naval hospital for the treatment of men on the active force. The rooms for beneficiaries filled at a slow pace, starting with five arrivals in 1834 and increasing to over 100 by 1845. Overall, some 541 men resided at the Naval Asylum in the years between its opening and the end of the Civil War in 1865.

The regulations governing admission changed several times during this period, but applicants were generally required to have served between 15 and 20 years. However, exceptions were sometimes granted. The 1834 regulations, for instance waived the service requirement for men who were disabled and had distinguished themselves by their heroism in battle or “other highly meritorious conduct in the public naval service.” Once admitted, residents could also be dismissed for drunkenness and other misdeeds. They could leave of their own accord, too.

Apparently satisfied with the services provided by the Naval Asylum, Congress in 1851 approved the opening of a second residency for Veterans in Washington, D.C. The U.S. Soldiers’ Home, as it came to be called, was reserved for men who had served in the Mexican War or in the Regular Army. After the Civil War, the government adopted this model of domiciliary care on a more ambitious scale through the establishment of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.

The National Home consisted of a network of residential communities in different parts of the country that offered room, board, and medical care to Union Veterans in need of assistance. The Naval Asylum in Philadelphia, meanwhile, after changing its name to the Naval Home in 1889, continued to operate well into the twentieth century until it closed in 1976 and relocated to Gulfport, Mississippi.

By Olivia Holly-Johnson

VSFS Intern, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.