Just after New Year’s Day in 1962, World War II Army Veteran Benjamin B. Belfer sent a letter to his U.S. Senator, Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, suggesting a simple yet powerful way for the government to honor deceased service members. The tradition at the time was for family members to receive the folded American flag that had been draped over the Veteran’s casket during the funeral service. Belfer proposed presenting the next of kin with a memorial certificate signed by the president of the United States in addition to the burial flag. The certificate, he wrote, would be “a keepsake that will never be forgotten by the family and relatives and friends of the departed Veteran.”

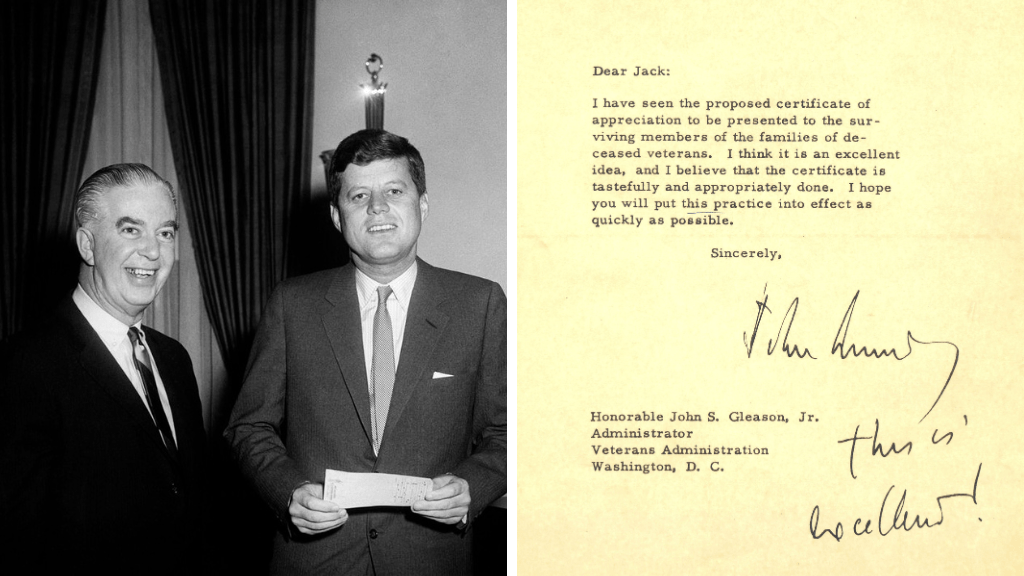

Belfer, who was the secretary-treasurer of the Minneapolis Joint Veterans Council, had become friendly with Humphrey 15 years earlier. The two had met when Humphrey was mayor of Minneapolis and Belfer was commander of the Minneapolis post of the Jewish War Veterans. After receiving Belfer’s letter in early January 1962, Humphrey wasted no time in sharing his idea with the head of the Veterans Administration, John S. Gleason, Jr. Gleason also saw the value in the proposal and in mid-February he put his staff to work on creating a design for the certificate and choosing the wording of the text. On March 6, the finished certificate was shown to President John F. Kennedy, Jr.. The following day, Kennedy sent Gleason a short note expressing his wholehearted approval. “I think it is an excellent idea, and I believe that the certificate is tastefully and appropriately done,” he wrote, adding that the issuing of certificates should begin “as quickly as possible.” Below his signature, he scrawled “this is excellent!” to emphasize his support for the project. In accordance with his wishes, the first 503 certificates went out in the mail in White House envelopes on March 20.

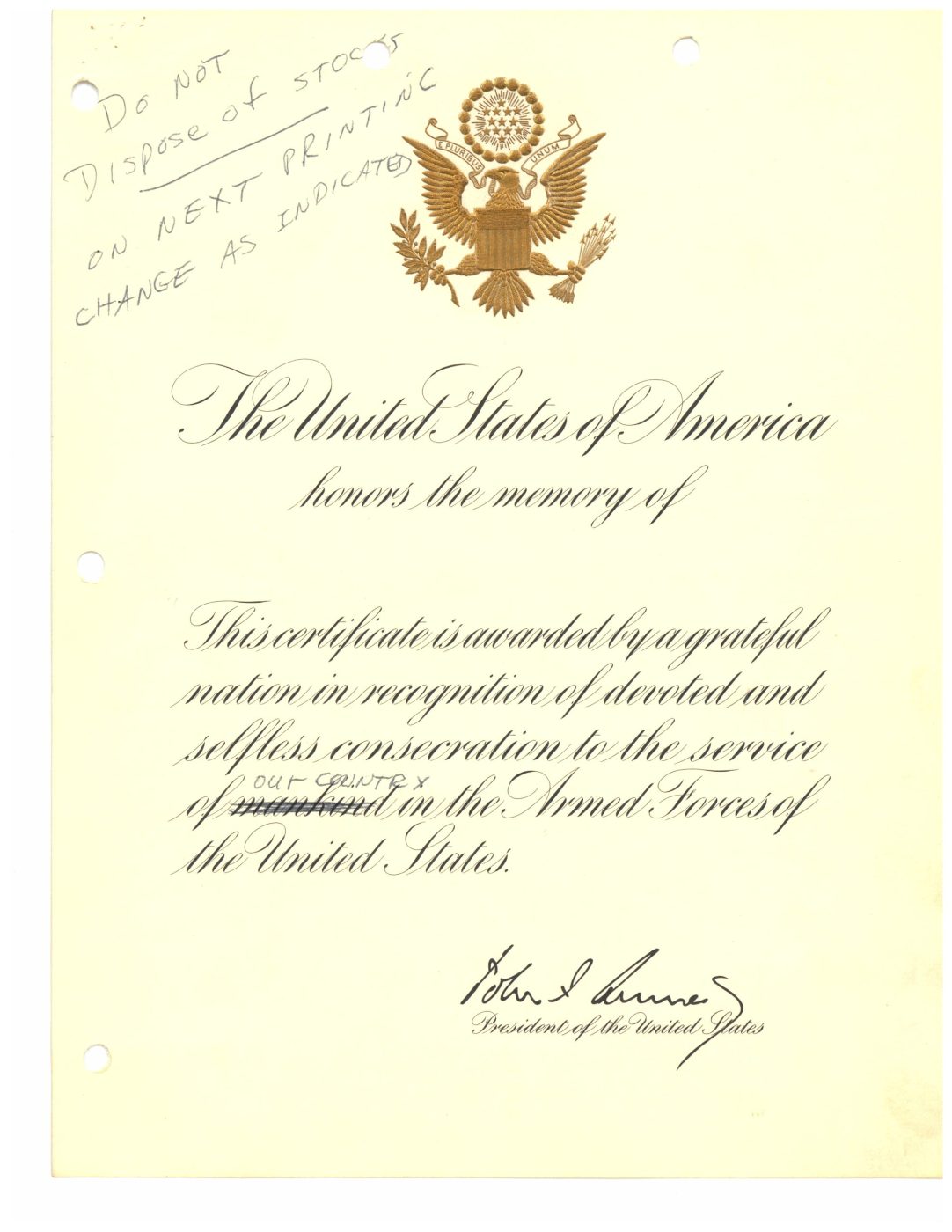

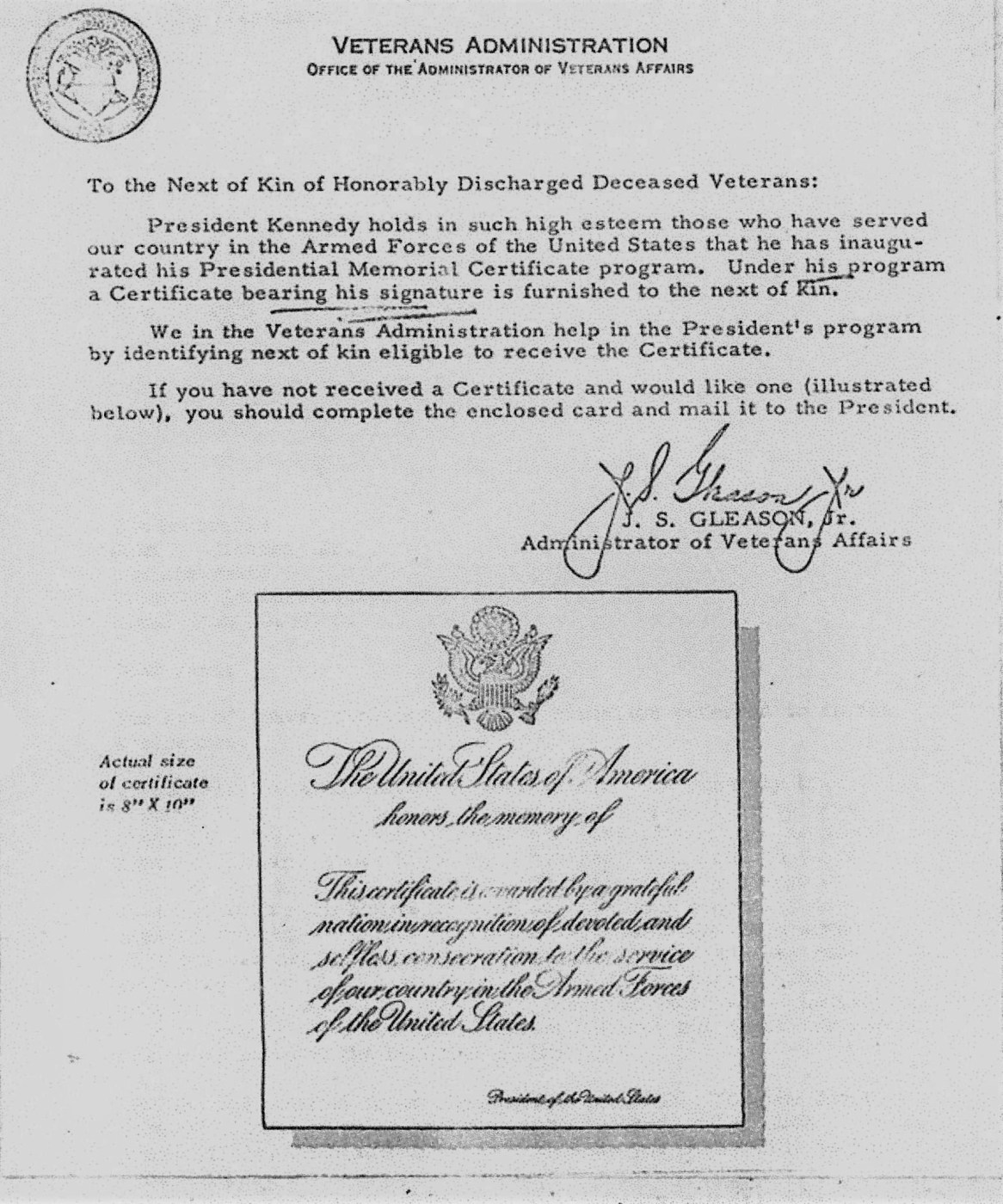

The Presidential Memorial Certificates were printed on 8.5 by 10-inch mid-weight, light-grey color paper stock and bore an embossed gold seal of the United States at the top. Beneath the name of the deceased appeared a brief message reading, “This certificate is awarded by a grateful nation in recognition of devoted and selfless consecration to the service of mankind in the Armed Forces of the United States.” In September 1962, at President Kennedy’s request, the wording was changed from “service of mankind” to “service of our country.” At first, VA limited the program to family members of Veterans who died after the March 1962 start date. Once VA received notification of a Veteran’s death, the Central Office automatically mailed the certificate to the deceased’s next of kin. VA sent out 220,000 certificates by this method over the first 16 months of the program.

The program proved enormously popular and the White House fielded a growing number of inquiries from relatives of Veterans who had died prior to March 1962 asking about their eligibility to receive a certificate. In April 1963, President Kennedy approved expanding the program to include these family members, too. To get the word out, VA arranged for a short note about the program along with an application card to be added to the monthly benefit checks that went out to surviving dependents. VA also made the certificates available upon request from the next of kin. VA estimated it would take about a year to get the memorial certificates into the hands of survivors of Veterans whose deaths predated the start of the program.

The assassination of President Kennedy on November 22, 1963, brought this effort to an abrupt halt. The issuing of certificates was suspended until President Lyndon B. Johnson gave the order to resume the program in early December. A few months later, however, the future of the program was cast into doubt when the Comptroller General of the United States completed a report questioning its legality. Released in May 1964, the report found that the spending of VA funds for the certificate program had never been authorized by law. The Comptroller General called for VA to either obtain ”specific statutory authority for the use of appropriations for the program” or discontinue it. In July 1964, VA took advantage of the language in a newly passed appropriation bill allowing VA to spend money on “expenses incidental to . . . [the] recognition of war veterans” to provide certificates to the next of kin of deceased Veterans who served in wartime. The following June, Congress placed the program on firm legislative footing by granting VA explicit authority to award certificates honoring all deceased Veterans who had received an honorable discharge.

Since the settling of its legal status, the Presidential Memorial Certificate program has continued without pause under every sitting president. In 2016, a new law broadened eligibility to include survivors of Active-Duty personnel, some Reservists and National Guard members, and Veterans with other-than-dishonorable discharges. Decades earlier, VA Administrator Gleason thanked World War II Veteran Benjamin Belfer for his suggestion “which will mean so much to the surviving relatives of our honored deceased Veterans.” The more than 20 million family members who have received a memorial certificate to date have reason to thank Belfer as well.

By Lily London

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, VA History Office Department of Veterans Affairs

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.