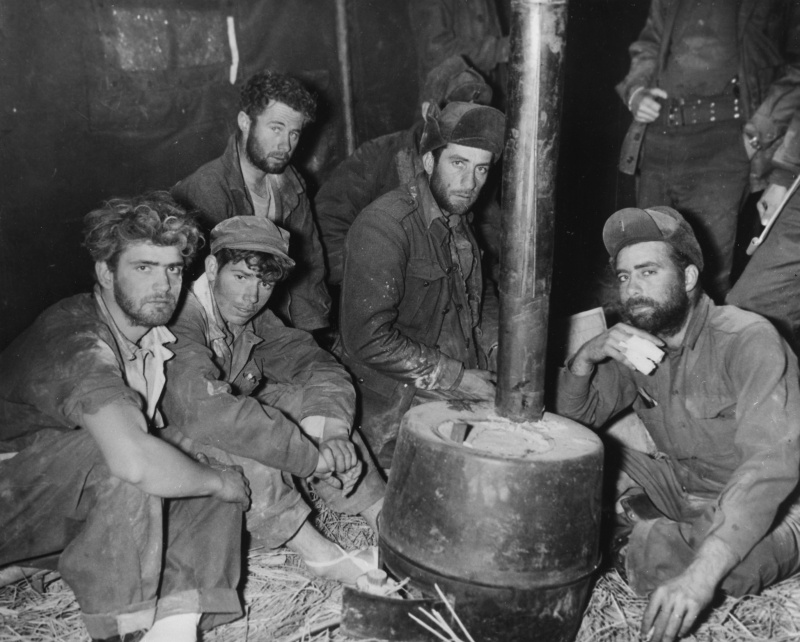

American service members taken prisoner in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam faced starvation, torture, forced labor, and other abuses at the hands of their captors. For those that returned home, their experiences in captivity often had long-lasting impacts on their physical and mental health. Recognizing all that they had suffered, the U.S. government has since World War II conferred special benefits on former prisoners of war to provide for their care and support.

During World War II, just over 130,000 Americans were captured by the Germans and Japanese. Roughly 116,000 survived the ordeal and returned to the United States at the war’s end. In 1948, Congress passed the War Claims Act awarding reparations to former prisoners (or their families if deceased) in the amount of $1.00 per day of captivity. These lump-sum payments, taken from seized German and Japanese assets, were intended to compensate prisoners of war for the inadequate food they received while held in confinement. Four years later, Congress revised the act to allow former prisoners to collect an additional $1.50 a day in compensation for “inhumane treatment” or other violations of the 1929 Geneva Convention. By 1955, over $123 million had been dispersed to World War II Veterans as part of this program. The law was amended again in 1954 to include the 4,418 Americans who were taken prisoner during the Korean War and later repatriated. Just under $9 million of newly allocated funds were distributed to these Veterans by August 1956.

In addition to reparations, former prisoners also benefited from legislation passed many years after World War II and Korea that expanded their eligibility for disability compensation and medical care from VA. Government-funded studies in the 1950s concluded that soldiers taken prisoner in World War II were more likely to develop disabilities compared to others who served in the conflict. These studies led to several legislative proposals to give former prisoners preferential treatment when it came to determining benefits. However, no action was taken by lawmakers until near the end of the Vietnam War. In 1970, Congress established a presumption of service connection for seven kinds of diseases and disorders affecting Veterans held prisoner for six months or longer. The presumptive designation meant that these conditions were automatically assumed to be related to the Veteran’s time in captivity. The ailments covered by the law included avitaminosis, malnutrition, chronic dysentery, and other nutritional deficiencies. Former prisoners diagnosed with such diseases were entitled to disability compensation and treatment at VA hospitals regardless of how much time had elapsed since their separation from service. Psychosis was also included but the symptoms had to present themselves within two years of discharge. The 1970 act applied not only to former prisoners from World War II and Korea, but also to service members captured during the still ongoing war in Vietnam.

In 1973, the United States withdrew the last of its combat troops from South Vietnam and the 591 Americans held prisoner in the North were released. Five years later, Congress ordered VA to carry out a thorough study of the disability and medical needs of former prisoners of war. Like previous investigations in the 1950s, the study confirmed that former prisoners of war had higher rates of service-connected disabilities. Former prisoners from World War II were 4-5 times more likely to develop service-connected disabilities than other military personnel in the same war. For those imprisoned during the Korean War, the rate was 11 times higher. At the same time, the report found that the repatriation exams of many former World War II and Korean War prisoners who filed compensation claims were less than thorough or even missing from their medical records.

The study did more than shed light on the prevalence of disabilities among former prisoners. It also outlined a series of recommendations to redress the shortcomings in the law and VA policies. For example, the report proposed eliminating the two-year time limit on psychosis, arguing that this disorder should qualify for full treatment no matter when the symptoms appeared. The study further recommended that VA “adopt a standardized protocol for disability compensation exams for all former [prisoners]” and have these exams conducted or supervised by physicians with expertise in the medical problems of these Veterans. It also called on the agency to create an advisory committee to continue to evaluate the medical data and research on former prisoners and provide guidance to VA leadership and staff.

Several of these recommendations came to fruition a mere year after release of the study. On August 14, 1981, President Ronald W. Reagan signed into law the Former Prisoners of War Benefits Act, the first piece of legislation that focused exclusively on the needs of Veterans who were held captive in wartime. The act adopted the study’s suggestion to remove the two-year presumptive period for psychosis. It also established an advisory committee on former prisoners to assess the effectiveness of VA’s efforts to serve these Veterans, recommend improvements, and report back to Congress with its findings. Finally, the bill extended presumptive benefits to Veterans imprisoned for as few as 30 days, as opposed to the six-month minimum required by the 1970 law.

The 1981 stature was not the last word on the subject. In response to new research, Congress and VA have continued to revise the rules and regulations for ex-prisoners to increase their access to VA benefits and medical care. Up-to-date information about benefits for former prisoners of war can be found on the VA website.

By Jordan McIntire

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, VA History Office, Department of Veterans Affairs

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.