Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ+) monuments adorn cemeteries across the United States, but only two are in national cemeteries maintained by VA. At Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery in Ellwood, Illinois, a four-foot-tall monument bears witness to the honorable service of LGBTQ+ Veterans. A smaller monument in the National Memorial Cemetery of Arizona in Phoenix recognizes all persons who have served their country with “courage and pride” throughout American history.

White text on a black background is standard for many memorials. However, the “pink triangle” serves as a focal point and symbol of pride on most LGBTQ+ monuments, including the two in the VA cemeteries. The pink triangle originated in Nazi Germany during the 1930s. Just as Jewish prisoners and citizens were forced to wear the yellow Star of David, those labeled as “homosexuals” were required to wear a pink triangle.

In the United States, blue rather than pink became the distinguishing mark for many LGBTQ+ Veterans. During World War II, the military issued thousands of other than honorable “blue discharges” to Army and Navy personnel. Printed on blue paper, these administrative discharges allowed the military to swiftly remove those who were considered troublesome or unfit for service. African American soldiers were often singled out for this type of discharge. So, too, were individuals accused of homosexual behavior or tendencies. Roughly 9,000 LGBTQ+ service members were given a blue discharge during the war. Afterwards, they were often denied their GI Bill benefits and other forms of recognition as Veterans, including the right to burial in national cemeteries.

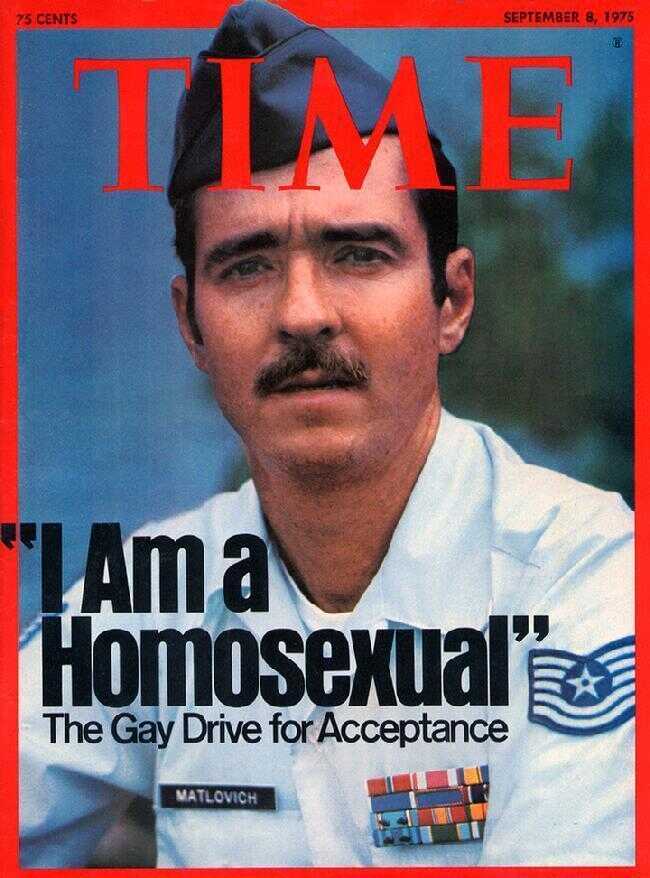

During the Cold War era, the armed forces continued to employ administrative discharges to expel gay men and women from the ranks. On average, about 2,000 persons a year were discharged due to their sexual orientation. Those who wanted to stay in the military had little choice but to keep their sexual identity hidden from view. In the mid-1970s, however, Air Force Tech Sgt. Leonard P. Matlovich decided to challenge the military’s policy of exclusion.

Matlovich had enlisted in 1963 and completed three tours in Vietnam, earning both a Purple Heart and Bronze Star. In 1975, he submitted a letter to his commanding officer openly declaring “that my sexual preferences are homosexual.” Despite his exemplary service record, he was administratively discharged. Matlovich then took his case to court and sued the Air Force for reinstatement. The legal battle dragged on for five years, but Matlovich prevailed in what was seen as a sign of hope for LGBTQ+ service members fighting for their rights.

Another significant development in the gay rights movement was its adoption of the pink triangle once used by the Nazis as a badge of shame. Activists in the 1980s turned the pink triangle into a mainstream LGBTQ+ symbol of both remembrance and pride. The first public monument to make prominent use of the symbol was Homomonument, built in Amsterdam in 1987 to memorialize the LGBTQ+ victims of Nazi persecution.

The pink triangle also became a key motif in Matlovich’s own memorial when he died in 1988 of complications from AIDS. Because government-issued headstones in national cemeteries can only display authorized emblems of belief and the inscription must include certain mandatory items, too, Matlovich chose a private plot in Washington, D.C.’s Congressional Cemetery. He wanted the headstone at his final resting place to be a memorial for all LGBTQ+ service members and Veterans. The design of the marker inspired that of the two LGBTQ+ monuments installed some years later in the VA cemeteries.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton enacted the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, which was intended to stop the active investigation of LGBTQ+ service members. While the limits of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” became apparent within the decade, the policy continued until it was repealed by President Barack Obama in 2011. In the intervening years, awareness of LGBTQ+ service members grew and LGBTQ+ rights groups became more vocal in demanding acceptance.

In 1999, the Phoenix chapter of Gay, Lesbian & Bisexual Veterans of America made plans for a memorial at National Memorial Cemetery of Arizona in Phoenix. The monument was carved of rainbow granite with two of the iconic pink triangles, inspired by the triangles on Leonard Matlovich’s headstone. While the type of stone was chosen to evoke the importance of the rainbow to the LGBTQ+ community, the inscription deliberately emphasized fellowship across sexual orientation and service lines, reading “In Memory of All Veterans Who Served with Courage and Pride.” The monument was unveiled at a ceremony held on Veteran’s Day in 2000.

With the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in 2011, individuals of all sexual persuasions were allowed to serve openly in the military. Shortly after, in 2013, VA approved the interment of same-sex spouses alongside Veterans in national cemeteries. Around the same time, the LGBTQ+ organization American Veterans for Equal Rights* began planning for a larger monument in a national cemetery.

After four years of application and design processes, the organization succeeded in getting a memorial approved by VA. Dedicated in 2015 at Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery in Illinois. The LGBTQ+ Veterans Memorial mirrored the designs seen on the Arizona memorial and Matlovich’s gravestone.

* Formerly the Gay, Lesbian & Bisexual Veterans of America. The organization changed its name in 2002.

By Matthew Harris

Intern, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

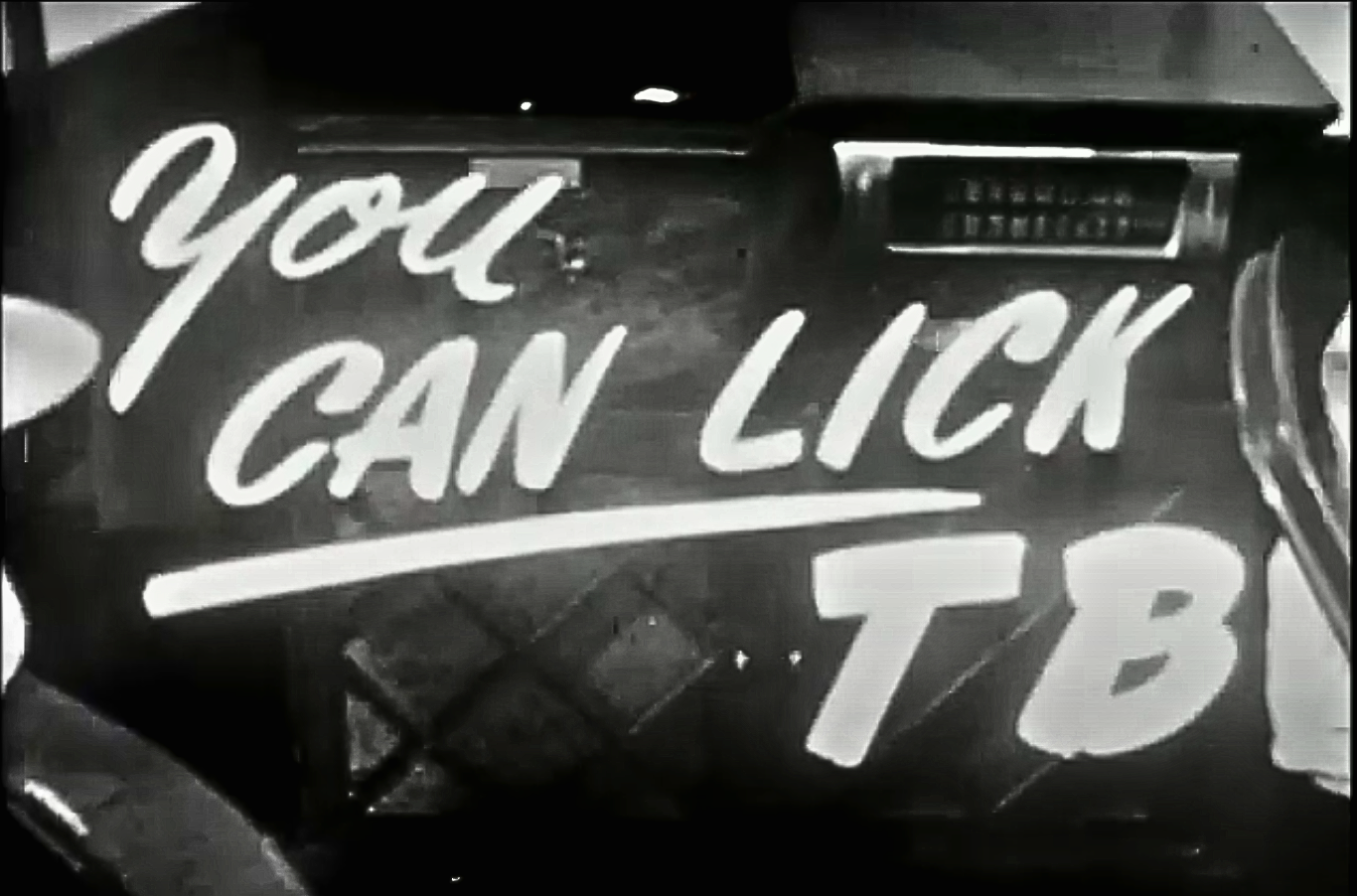

Object 89: VA Film “You Can Lick TB” (1949)

In 1949, VA produced a 19-minute film titled “You Can Lick TB.” The film follows a fictional conversation between a bedridden Veteran with tuberculosis and his VA doctor, dramatizing through brief vignettes the different stages of TB treatment and recovery.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 88: Civil War Nurses

During the Civil War, thousands of women served as nurses for the Union Army. Most had no prior medical training, but they volunteered out of a desire to support family members and other loved ones fighting in the war. Female nurses cared for soldiers in city infirmaries, on hospital ships, and even on the battlefield, enduring hardships and sometimes putting their own lives in danger to minister to the injured.

Despite the invaluable service they rendered, Union nurses received no federal benefits after the war. Women-led organizations such as the Woman’s Relief Corps spearheaded efforts to compensate former nurses for their service. In 1892, Congress finally acceded to their demands.

History of VA in 100 Objects

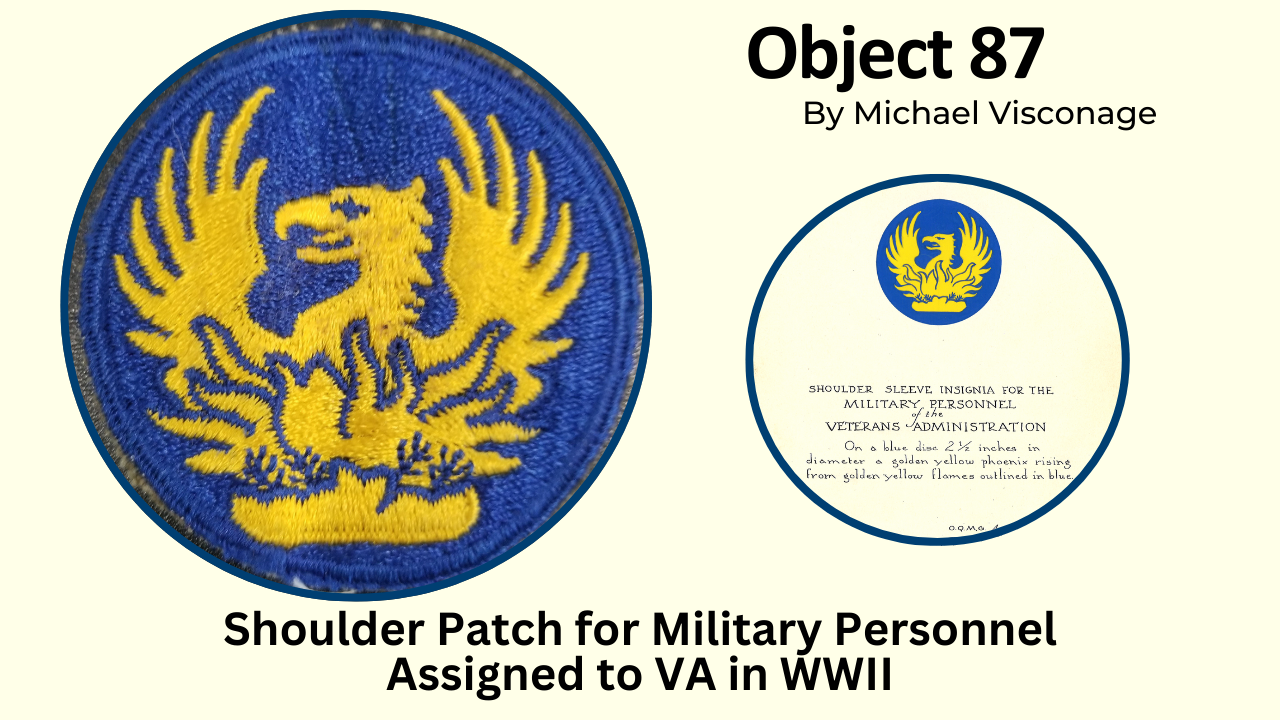

Object 87: Shoulder Patch For Veterans Administration Military Personnel in World War II

For a time during and after World War II, active duty military personnel were assigned to the Veterans Administration.

That assignment was represented by a blue circle with a golden phoenix rising from the ashes. This was the shoulder patch worn by the more than 1,000 physicians, dentists, and other medical professionals serving in the U.S. Army at VA medical centers.

This was the same patch worn by Gen. Omar Bradley during his time as VA administrator after the war concluded.