The liver performs hundreds of functions vital to the health of the human body. It produces bile to assist with digestion; processes nutrients, medications, and hormones; makes proteins for blood clotting; removes toxins from the blood; and regulates immune responses. The liver also has regenerative properties, but once the damage from disease goes beyond the organ’s threshold for healing itself, the consequences can be catastrophic.

Prior to the 1960s, liver failure always ended in death. In May 1963, however, Dr. Thomas E. Starzl made medical history at the VA hospital in Denver, Colorado, when he performed the first liver transplantation on a patient who survived the operation. The patient was William G. Grisby, a 48-year-old janitor admitted to a community hospital with symptoms suggesting a peptic ulcer. Exploratory surgery revealed that cancer had enveloped about a third of his liver although it had not metastasized. With his health failing quickly, he was transferred to the VA hospital for the transplant surgery. His donor was a 55-year-old Veteran who had just died of a brain tumor.

The outcome was fleeting, as Grisby died a few weeks later of complications from the surgery. But his new liver was functioning to the end. The case provided a glimmer of hope, demonstrating that it was, in fact, possible to replace a diseased liver with a healthy one from a donor. It also offered a glimpse of the future. In time, after two more decades of research and testing, much of it led by Starzl himself, liver transplantation would fulfill its promise and became a dependable, life-extending treatment for children and adults suffering from end-stage liver disease.

Starzl’s experimental work on liver transplantation in canines early in his career convinced him that the same procedure could be performed on humans. A Navy Veteran, he had earned a medical degree and doctorate from Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago in the early 1950s.

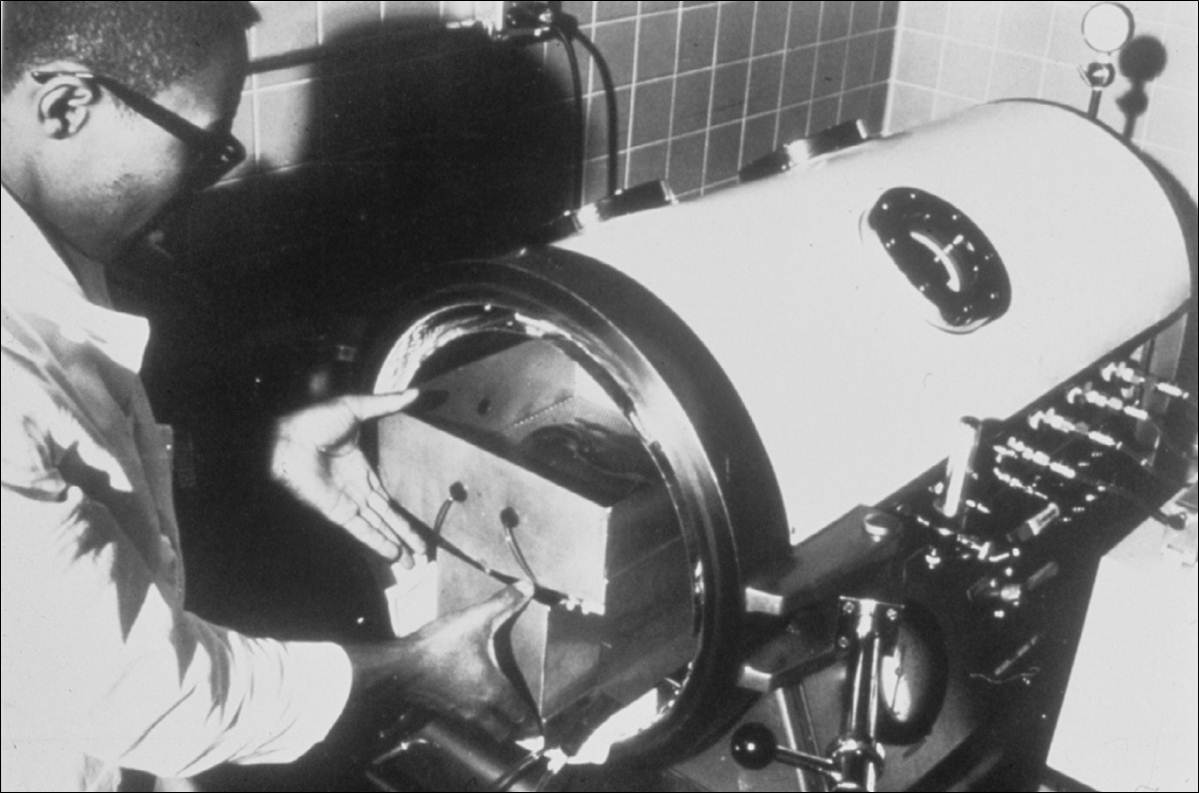

He returned to Chicago in 1958 to serve as resident surgeon at the Chicago VA medical center. There, he launched his research program with dogs, which he expanded after joining the surgery department at Northwestern a year later. While at Northwestern, he carried out 79 liver transplants on canine test subjects. These experiments generated vital knowledge on donor liver preservation and surgical techniques to redirect blood flow that proved foundational to the emerging field of solid organ transplantation.

In late 1961, Starzl took up a new position as chief of surgery at the Denver VA hospital. His VA salary paid for his concurrent appointment at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. As Starzl recalled in his 1992 autobiography, he was recruited to join the school’s department of surgery for one overriding purpose: “to bring liver transplantation to clinical use.”

He started, however, with kidney transplantation, a procedure that surgical teams in other locations had completed with intermittent success starting in 1954. Starzl quickly surpassed those earlier efforts, thanks in part to a new drug protocol that reversed the effects of organ rejection. This immunosuppression regimen was derived from his continued experimentation with dogs at the VA research lab in Denver. From November 1962 to March 1964, he performed 64 living-donor kidney transplants. A later analysis of the kidney transplant registry carried out in 1989 found that 15 of the original patients from this group were still alive.

Liver transplantation presented a far more complex challenge and Starzl’s first attempt at the surgery in March 1963 ended in failure, with the patient dying on the operating table. He tried again two months later with William Grisby. Starzl and his team performed the historic transplantation on May 5, 1963. A week after the operation, Grisby was able to sit up and feed himself. However, his condition took a turn for the worse two weeks later and he died on May 27 from pneumonia brought on by a respiratory infection.

Starzl performed three more liver transplants in 1963 with identical results: the patients lived for up to 23 days but succumbed to post-operative infections. In all four cases, though, autopsies showed good liver function and little sign of organ rejection.

Dr. Starzl put the liver transplantation program on hiatus for four years and refocused on his research with dogs in the VA lab. This work yielded advances in surgical techniques, post-operative care, and drug therapy to reduce the risk of rejection.

He resumed the transplant surgeries in 1967, performing the procedure on 165 patients from 1967 to 1979. The outcomes were much better, with 18 patients living for 20 years or longer although the overall one-year survival rate was only about 33 percent. In 1979 and 1980, Starzl and researchers in Europe achieved a string of breakthroughs with immunosuppression treatments that dramatically improved the prognosis for transplantation patients. The one-year survival rate jumped to 70 percent. In 1981, Starzl moved his program to the University of Pittsburgh, where he established what would soon become the world’s leading liver transplantation center.

In an article published in 1982, Dr. Starzl reflected on the long and twisting path that brought his pioneering work on liver transplantation to this point: “The history of medicine is that what was inconceivable yesterday and barely achievable today often becomes routine tomorrow.” By the time he retired from clinical practice in 1991, liver transplantation had indeed become routine, with transplant centers opening in all parts of the country. Over 100 hospitals in the United States now offer this service, including six at VA, and about 75 percent of transplant recipients live for five years or longer.

By Stacy A. Mince

Historian, VISN 19, Veterans Health Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.