In 1946, Americans were adjusting to life in the immediate aftermath of World War II. Post-war concerns were varied. Would there be another economic depression? Would political unrest grow in Europe or Asia? Would there be another war?

Across the country, communities were also confronting more immediate questions related to their returning Veterans. How would the 16 million Americans who served in uniform transition back into civilian society? How would disabled Veterans be cared for and rehabilitated? Could men and women who experienced the traumas of war return to “normal” life?

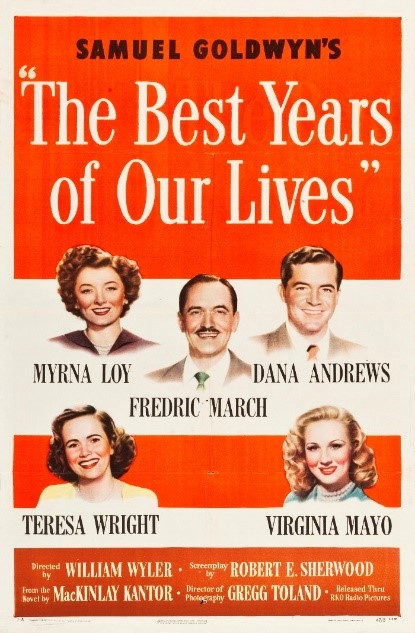

On November 21, 1946, The Best Years of Our Lives opened in movie theaters. The film was praised for its frank portrayal of the transition from military service to Veteran status as seen through the eyes of its three main characters returning to their hometown after the war. The trio of combat Veterans–a sailor, infantry sergeant, and air corps bombardier–meet by chance while demobilizing. The story follows them through their readjustment, as they experience bouts of Post-Traumatic Stress, attempt to reestablish family and marital relationships, meet with reemployment challenges, and struggle with alcohol abuse. The film also examines the varied reactions to their service and sacrifice from members of their communities who perceive them in ways ranging from hero to threat.

The sailor, portrayed by Harold Russell, also contends with the severe service disability of the double amputation of his hands. Russell’s performance was poignantly authentic. An Army Veteran, Russell lost both hands during an explosives training accident during the war.

The Best Years of Our Lives was a huge box office success, making over $10 million during its initial release and ending the year as the highest grossing film of 1946. It also received eight Academy Awards, including two for Russell: one for best supporting actor and a second honorary Oscar for his courage and inspiration to fellow Veterans. Russell remains the only actor to receive two Academy Awards for the same performance.

General Omar Bradley, head of the VA during this key post-war period, was so impressed by the film that he arranged for it to be shown to VA headquarters staff. Bradley also wrote the film’s producer, Samuel Goldwyn to express his appreciation for the film: “I cannot thank you too much for bringing this story to the American public.”

Reviewing the film in retrospect, movie critic Roger Ebert commented, “Seen more than six decades later, it feels surprisingly modern: lean, direct, honest about issues that Hollywood then studiously avoided. After the war years of patriotism and heroism in the movies, this was a sobering look at the problems veterans faced when they returned home.”

By Michael Visconage

Chief Historian, Department of Veterans Affairs

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.