Former VA nurse and Army National Guard Colonel (Ret.) Margarethe Cammermeyer believes that people should, in her words, “live their truth.” But her own efforts to abide by that credo led to her dismissal from the military in 1992. Her legal battle for reinstatement inspired the 1995 television movie “Serving in Silence,” starring Glenn Close and produced by Barbra Streisand. After her victory in court, Cammermeyer continued her mission throughout the remainder of her career at VA and in the National Guard and for more than two decades after her retirement.

Cammermeyer was born in Nazi-occupied Norway during World War II. She later immigrated to the United States with her family and became an American citizen in 1960. She enlisted in the U.S. Army at age 19 through the service’s Student Nurse program. After completing her training, she was initially stationed in the U.S. and Germany before requesting an assignment in Vietnam in 1967. The Army sent her to the 24th Evacuation Hospital at Long Binh, where she led a neurosurgical intensive care unit and earned a Bronze Star for meritorious service.

Her time on active duty came to an abrupt end when Cammermeyer, who had married an Army officer, became pregnant. The Army discharged her and she embarked on a new career as a registered nurse with VA. In 1970, she went to work at the VA Medical Center in Seattle, Washington. Two years later, a change in Army policy allowed her to join the Washington State National Guard.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Cammermeyer juggled her VA and reserve duties, while also earning a master’s degree in nursing (followed by a doctorate in 1991) and raising a family of four children. She eventually rose to the rank of Colonel in the Guard. At VA, Cammermeyer received the agency’s highest award for Excellence in Nursing in 1985. She was lauded “for improving the quality of care and the quality of life for patients with neurodysfunction and developing a growth model of self-care which was incorporated into the curriculum at other nursing schools.”

By the late 1980s, Cammermeyer was one of the most respected nurses at VA and she had ambitions of becoming Chief Nurse of the Army National Guard. But it was at this juncture in her life that she also came to terms with her sexual identity. She openly stated this fact during a routine security-clearance interview conducted when she applied to the Army War College in 1992. She was, once again, forced out of the military, this time for violating the Pentagon’s longstanding policy against allowing homosexuals to serve. She was the highest-ranking officer to date to be discharged for this cause.

Cammermeyer, however, refused to accept her dismissal without fighting back. She took her case to court and won. In June 1994, a judge ruled in her favor and ordered her restored to her former rank. Her lawsuit not only brought her personal vindication but also raised public awareness of the military’s discriminatory practices.

While her struggle and eventual triumph inspired many, Cammermeyer’s story struck a particular chord with superstar actress and singer Barbra Streisand, who called it “the most important social issue of the decade.” Eager to bring the story to a wider audience, Streisand met with Cammermeyer and signed on to produce a made-for-tv movie about her experiences. Cammermeyer was portrayed in the film by actress Glenn Close, who shared executive producing credits with Streisand.

The movie “Serving in Silence,” based on Cammermeyer’s memoir of the same name, premiered in February 1995 on NBC. The film, like the true-life story it recounted, was groundbreaking for it was broadcast at a time when representation and plotlines were rarely seen on network television. The highly praised drama earned many honors, including a Peabody Award and three Emmys.

Cammermeyer herself retired in 1997 after 27 years at three VA medical centers on the West Coast and 31 years of service in the Army and the Army National Guard.

By Katie Rories

Historian, Veterans Health Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 88: Civil War Nurses

During the Civil War, thousands of women served as nurses for the Union Army. Most had no prior medical training, but they volunteered out of a desire to support family members and other loved ones fighting in the war. Female nurses cared for soldiers in city infirmaries, on hospital ships, and even on the battlefield, enduring hardships and sometimes putting their own lives in danger to minister to the injured.

Despite the invaluable service they rendered, Union nurses received no federal benefits after the war. Women-led organizations such as the Woman’s Relief Corps spearheaded efforts to compensate former nurses for their service. In 1892, Congress finally acceded to their demands.

History of VA in 100 Objects

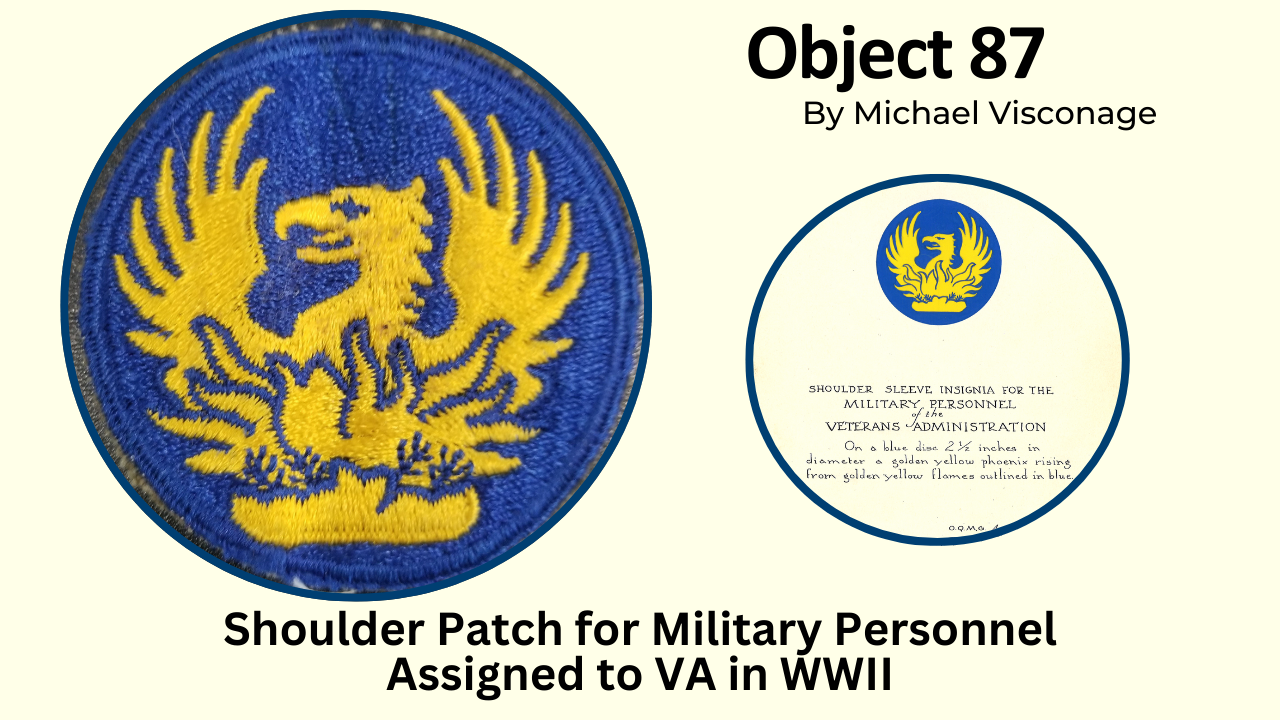

Object 87: Shoulder Patch for Veterans Administration Military Personnel in World War II

For a time during and after World War II, active duty military personnel were assigned to the Veterans Administration.

That assignment was represented by a blue circle with a golden phoenix rising from the ashes. This was the shoulder patch worn by the more than 1,000 physicians, dentists, and other medical professionals serving in the U.S. Army at VA medical centers.

This was the same patch worn by Gen. Omar Bradley during his time as VA administrator after the war concluded.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 86: The Roll of Honor

“The following pages are devoted to the memory of those heroes who have given up their lives upon the altar of their country, in defense of the American Union.”

So opened the preface to the first volume of the Roll of Honor, a compendium of over 300,000 Federal soldiers who died during the Civil War and were interred in national and other cemeteries. The genesis of this 27-volume collection published between 1865 and 1871 can be traced to Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs and the department he oversaw for a remarkable 21 years from 1861 to 1882.