The Civil War Veterans who resided in the barracks or entered the hospital at the Central Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (NHDVS) in Dayton, Ohio, knew that the home cemetery was most likely going to be their final resting place. Then as now, burial was among the government benefits provided to those who served honorably. At the Dayton campus, home to more than 5,000 ”inmates” at the turn of the twentieth century, a Veteran’s last journey, reported the Cincinnati Enquirer, followed a literal “underground path of death.” Dayton’s Tunnel terminated at a gated portal on the edge of what is now Dayton National Cemetery.

This subterranean route, 300 feet long from hospital to cemetery, is a remnant of the late nineteenth-century network of tunnels excavated to hold pipes that moved steam heat, sewage, and utilities throughout the campus. It began below the chief surgeon’s headquarters in the Victorian three-story, 300-bed hospital at a “dead-room”—an underground apartment containing the morgue and storage for a supply of new coffins. Lights illuminated the tunnel, 8 feet across and 7 feet tall. It was improved in 1887 with a new receiving vault hailed as a “very great convenience to the institution.”

The Cincinnati Enquirer story about life at the home, published in 1891, describes the Veteran’s last journey and final honors. From the dead-room, “the casket containing the remains of the old hero is placed on a small, flat car” that transports it through the tunnel to the opening at the edge of the cemetery:

[At the entrance,] a guard in waiting unlocks the heavy iron gates, which swing open and the casket is received by the funeral corps and placed in the hearse in waiting. A line of forty or more soldiers has already been formed. The casket is borne to the church where the funeral services are held. Then the procession forms in line and the cemetery is reached in a short time. The body is interred and a salute is fired, and all is over.

One Veteran reflected, “Our little cemetery over yonder is growing larger and larger. Not a day passes that does not see one or more of us go through the tunnel.” He was right. Between 1890 and 1900, an average of 383 residents of the Central Branch died annually.

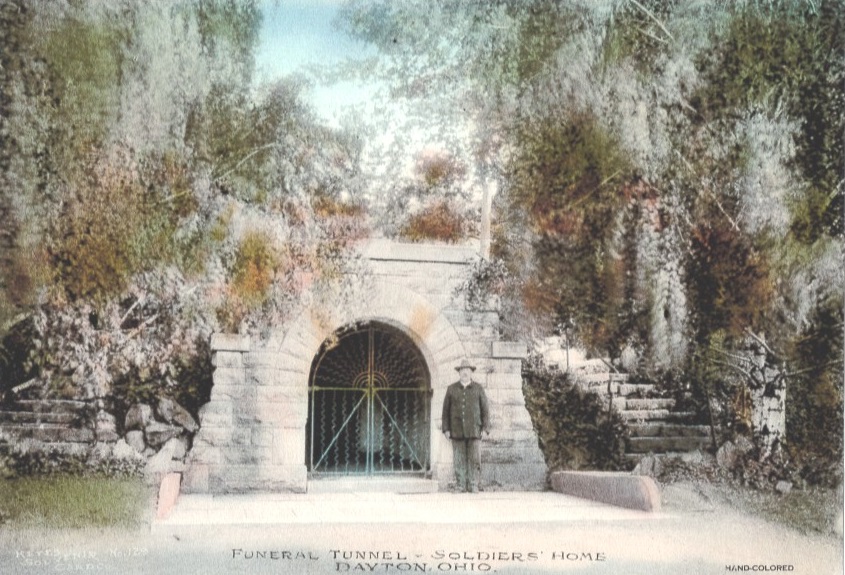

After the original hospital was demolished in the 1940s, the brick-lined passage was sealed off at both ends. To passersby, the opening in the cemetery remains the only visible evidence of the tunnel. Its current appearance contrasts starkly with its historic countenance, which is best preserved in picture postcards. The once-elegant portal is barely recognizable: the entrance is sealed up, the dressed stonework and metal gates are gone, and the stone steps descending into the cemetery on each side of the former opening are encroached by the steep grassy slope. The tunnel opening, like so many other long-lost features of the historic Central Branch, attracted thousands of visitors in its heyday. In an incongruous juxtaposition, the image was even printed on souvenir ceramic soap dishes sold at the home’s newsstand along with postcards.

The funeral tunnel at Dayton is a unique VA historic resource that has been documented and evaluated by engineers and historic preservationists using non-invasive ground-penetrating radar, digital photogrammetry, and low-light photography, among other techniques. Stakeholders at VA and non-profit partners are optimistic that the portal in the cemetery may be restored to its original appearance along with a representative portion of the tunnel to interpret the history of the Veteran’s last journey. The Dayton NHDVS campus, including the cemetery, was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 2012.

By Sara Amy Leach

Senior Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.