In 1832, the federal government found itself with a pension problem largely of its own making. In June, Congress passed a law granting a pension to all surviving Revolutionary War Veterans who had served in any capacity for at least six months. Previously, pensions had been limited to Veterans disabled by wartime injury or, after 1818, to those in financial need.

One of the new law’s staunchest supporters in the Senate argued that the country could afford to be generous, as he believed no more than 10,000 Veterans were still alive and eligible to claim the benefit and the costs to the government would be modest. In fact, the senator’s estimations were badly off the mark. By year’s end, 24,000 applications had been received and the projected expense was four times greater than anticipated.

The influx of applications overwhelmed the small office in the War Department responsible for processing them. As head of the department, the Secretary of War was nominally in charge of the pension system, but the day-to-day business of the office was conducted by a head clerk and sixteen other clerks. As of early January 1833, they had reviewed only one-third of the submitted claims and half of those examined had been returned with requests for more documentation.

Lewis Cass, who had been appointed Secretary of War in 1831 by President Andrew Jackson, blamed the office’s struggles on the fact that it lacked an executive officer with the necessary authority to manage the clerical staff and make decisions.

“There is no doubt that this state of things has impaired and, as long as it continues, will impair the operations of the department,” he wrote Congress in response to its inquiry about execution of the 1832 act. Cass asked lawmakers to create a Commissioner of Pensions position with duties clearly defined by statute. In his view, for the commissioner to be an effective leader and administrator, his office “should have a legal existence, an efficient control, and an acknowledged responsibility.”

Congress agreed with his proposition and included a provision in the March 1833 appropriation bill granting the president the authority to appoint a pensions commissioner. However, legislators limited the office’s existence to two years, leaving it to later sessions to decide if the position should be continued. The chief clerk at the time, James L. Edwards, was named the first Commissioner of Pensions, a promotion that increased his annual salary from $1,600 to $2,500. He was the logical choice.

Born around 1786, Edwards enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1811 and earned a silver medal for his actions aboard the frigate United States during the War of 1812. He became chief clerk at the pension office in 1818, the same year Congress approved the first general service pension law permitting Revolutionary War Veterans without disabilities to file claims. Edwards helped the War Department weed out thousands of applications from ineligible claimants and he also cleaned house of clerks suspected of wrongdoing.

Both the office and his appointment proved to be lasting. Congress after 1833 periodically voted to renew the commissioner’s position before finally dropping in 1849 all references to the law expiring after a set amount of time. Edwards served as commissioner throughout this period, weathering five changes in presidential administrations. Under his steady leadership, the pension office tackled the huge backlog in claims resulting from the 1832 act, eventually issuing over 32,000 pensions to Veterans of the war. During his tenure as commissioner, Edwards also continued his crusade against corruption, instituting various checks in the pension payment process and other reforms to reduce the incidence of fraud and graft.

In July 1850, President Zachary Taylor died unexpectedly and his vice president, Millard Fillmore, assumed office. In November, Edwards was finally replaced as Commissioner of Pensions by James E. Heath. The circumstances of his departure are murky. Edwards was in his mid-sixties and, with more than three decades of public service to his name, he may have simply decided to retire. However, it is also possible that Fillmore wanted to appoint a commissioner of his own choosing. Heath was a man of many talents—writer, editor, politician, and public auditor with thirty years of experience, which prepared him well for the commissioner’s position.

He served less than three years, though. The inauguration of Franklin Pierce as president in March 1853 resulted in the appointment of a new commissioner two weeks later. For the remainder of the century and into the next, commissioners rarely lasted for more than one administration and most owed their appointments to political patronage rather than their qualifications for the job. Many would still turn out to be dedicated public servants, but none would come close to matching James Edwards’ length or record of service. The position was abolished when the Veterans Administration absorbed the Pension Bureau in 1930.

By Scott Hudson

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

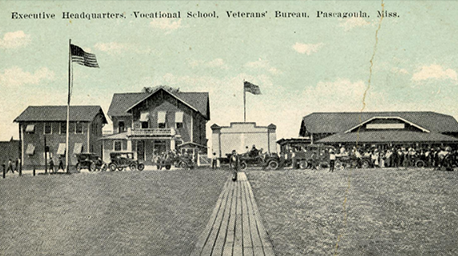

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.